The hunt to decode one of the world’s strangest writing systems has shifted from a fringe obsession to a serious scientific effort, powered by new tools and a fresh generation of researchers. What once looked like an impenetrable wall of symbols is starting to yield patterns, rules and even glimpses of the people who used it.

As I trace how this work is unfolding, I see a story that is less about a single breakthrough and more about a slow, methodical unravelling of a code that resisted understanding for decades. The result is a rare moment when linguistics, archaeology and computing intersect to illuminate a language that had seemed permanently out of reach.

Why this “weirdest language” captured the world’s imagination

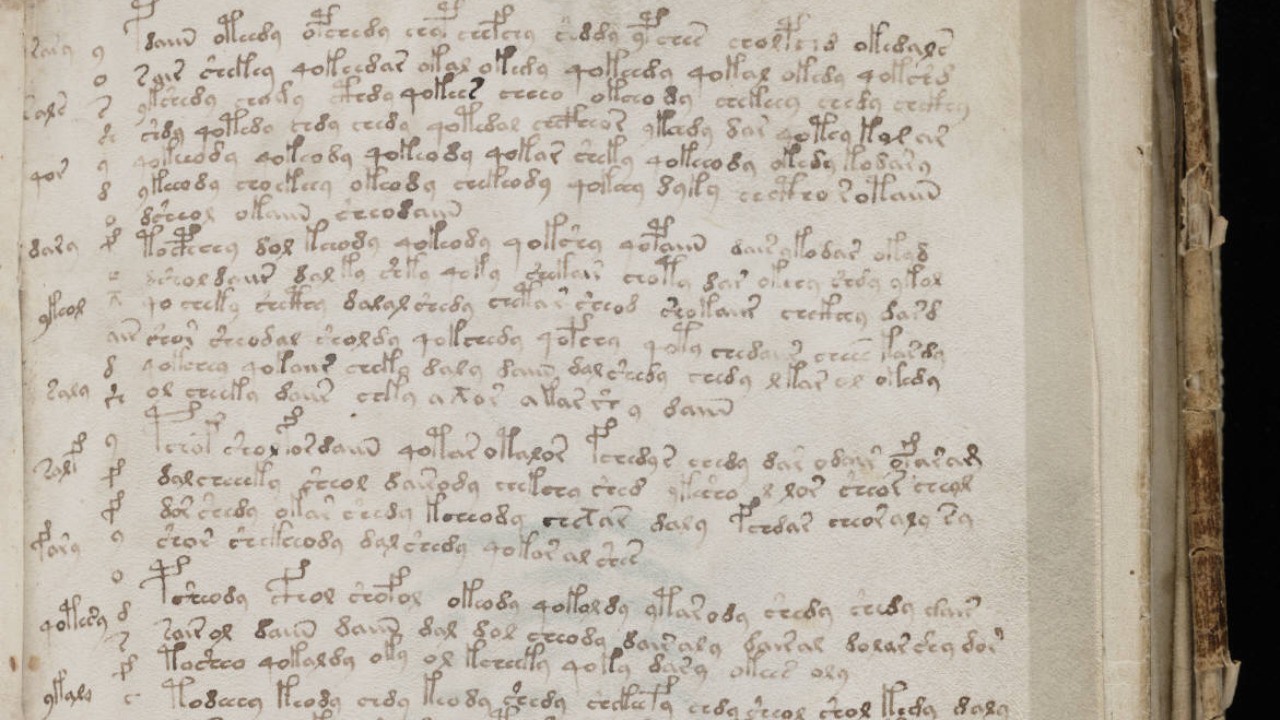

Every era has its intellectual puzzles, and in historical linguistics, the most alluring ones are scripts that no one alive can read. The system now being described as the “weirdest language of all time” sits at the extreme end of that spectrum, with symbols that do not map cleanly onto any known alphabet, syllabary or logographic tradition. For years, it lived in the margins of scholarship, treated as an oddity that might never be fully understood, which only deepened its mystique among codebreakers and amateur sleuths.

What changed is that specialists began to treat this script less as a curiosity and more as a structured system that could be attacked with the same discipline used on other undeciphered texts. In coverage that framed it as the “weirdest language of all time”, researchers highlighted how its unusual shapes, repetition patterns and apparent lack of obvious cognates made it a perfect stress test for new decipherment methods. That framing pulled the story out of niche conferences and into mainstream attention, turning a technical project into a cultural phenomenon.

What makes this language so strange in the first place

To understand why experts label this system as uniquely odd, I start with its internal structure. The symbols do not behave like the letters of an alphabet, where each sign maps to a single sound, nor do they act like the characters of a typical logographic script, where each sign stands for a word or morpheme. Instead, the inventory appears to mix functions, with some signs repeating in tight clusters and others appearing only once or twice across the surviving corpus. That blend of regularity and rarity is a nightmare for anyone trying to build a phonetic or semantic map.

Equally striking is how little the script seems to borrow from its neighbors. In most ancient writing systems, you can spot shared roots, borrowed signs or parallel conventions that hint at family ties. Here, the shapes and ordering rules look almost sui generis, which means researchers cannot lean on the usual comparative shortcuts. The result is a language that feels alien even to seasoned epigraphers, not because it is inherently more complex than others, but because it refuses to line up neatly with the typologies that normally guide decipherment.

From curiosity to code: how researchers finally gained traction

The turning point came when linguists and computer scientists stopped waiting for a Rosetta Stone style bilingual inscription and instead treated the existing material as a dataset ripe for pattern analysis. Rather than guessing meanings sign by sign, they began by charting frequencies, positional tendencies and co-occurrence patterns across every known inscription. That shift from impressionistic reading to quantitative modeling allowed them to test hypotheses about word boundaries, grammatical markers and possible sound values with far more rigor.

At the same time, field specialists re-examined the archaeological context of each inscription, cross-referencing find spots, associated artifacts and stratigraphic layers. By tying specific texts to particular sites, trade routes or ritual spaces, they could infer likely domains of use, from administrative tallies to religious dedications. Those contextual clues, combined with statistical models, gave the first solid footholds: recurring sign clusters that plausibly marked personal names, place names or standard formulae, which in turn anchored the broader decoding effort.

The role of AI and pattern recognition in cracking the script

As the corpus was digitized, machine learning tools entered the picture, not as magical decoders but as tireless pattern hunters. Researchers trained algorithms to recognize individual signs across damaged or stylized inscriptions, standardizing the dataset so that every instance of a symbol could be counted and compared. That automated cataloging solved a basic but crucial problem: in a script with dozens or hundreds of signs, human eyes alone struggle to track subtle variations and rare combinations at scale.

Once the symbols were consistently tagged, more advanced models could search for higher order regularities, such as recurring sequences at the start or end of lines, or clusters that tended to appear near numerals or pictorial motifs. These patterns did not instantly reveal meanings, but they narrowed the range of plausible interpretations. For example, a sequence that reliably appears before what archaeologists identify as commodity markers is a strong candidate for a verb like “to give” or “to receive,” while a cluster that repeats only in funerary contexts might encode a title or epithet. AI, in this sense, became a microscope for structure rather than a black box translator.

What “being deciphered” actually means in practice

When headlines say a language is “finally being deciphered,” it can sound as if scholars suddenly woke up with a full dictionary and grammar in hand. The reality is more incremental and, in my view, more impressive. Decipherment usually begins with a handful of secure identifications, such as proper names or numerals, and then radiates outward as those anchors help decode neighboring signs and grammatical patterns. In this case, researchers are still in the phase where they can read parts of the system with confidence while other sections remain opaque.

Practically, that means experts can now recognize recurring formulae, probable word boundaries and some structural features like suffixes or prefixes, even if they cannot yet translate every line into a modern language. They can say with some confidence that a given inscription records a transaction, a dedication or a legal agreement, based on the arrangement of signs and their parallels across the corpus. That partial understanding is what justifies the claim that the script is “being deciphered” rather than simply “studied,” even though a full bilingual glossary remains a long term goal rather than a present reality.

How the decipherment reshapes our view of the people behind it

Every new insight into the script feeds back into a larger question: who used this language, and what kind of society produced it? As researchers identify patterns that look like personal names, titles or place references, they begin to sketch a social landscape that had previously been little more than guesswork. The emerging picture suggests a community with formalized record keeping, specialized scribes and a shared set of conventions that extended across multiple sites.

Even partial readings can shift long standing assumptions. If a cluster of signs once thought to mark religious offerings turns out to encode quantities and commodities, then what looked like a temple inventory might instead be a tax ledger. That kind of reclassification changes how I understand power, trade and belief in the culture that used the script. Decipherment, in other words, is not just about matching symbols to sounds; it is about reinterpreting an entire archaeological record through the lens of a language that is finally starting to speak.

Why this breakthrough matters beyond one obscure script

The techniques honed on this unusually stubborn language are already influencing how scholars approach other undeciphered systems. By proving that a mix of computational analysis, contextual archaeology and traditional philology can make headway even without a bilingual key, the project offers a template for tackling scripts that once seemed hopeless. That methodological legacy may ultimately matter as much as the specific words now being teased out of these inscriptions.

There is also a broader cultural impact. When a language long dismissed as unreadable begins to yield meaning, it challenges the assumption that some parts of the human past are permanently sealed off. For students, hobbyists and communities connected to the regions where these texts were found, the slow decoding of this script is a reminder that patience and collaboration can recover voices that history nearly erased. In that sense, the “weirdest language of all time” is becoming something more familiar: another human attempt to record life, power and belief, finally coming back into focus.

The next frontiers: from partial readings to fluent understanding

Even as researchers celebrate the current progress, they are clear about how much remains to be done. Large portions of the vocabulary are still unknown, and key grammatical structures are only tentatively mapped. Moving from recognizing set phrases to parsing complex, unique sentences will require more inscriptions, better imaging of damaged texts and continued refinement of statistical models that can test competing hypotheses about syntax and semantics.

The path ahead will likely involve a feedback loop between new discoveries in the field and fresh analyses in the lab. Each newly unearthed inscription, especially if it appears in an unusual context or preserves longer passages, can either confirm existing readings or force a rethink of cherished assumptions. As that process unfolds, the language will move from being “partly cracked” to something closer to a working medium of communication, where scholars can not only identify what a text is about but also appreciate its nuance, style and perhaps even humor. At that point, the strangest language on the planet will feel less like a puzzle and more like a conversation, delayed by centuries but finally resumed.

More from MorningOverview