On a dusty test site in Australia, a spider-like robot is quietly rewriting the rules of construction, extruding walls in looping arcs instead of stacking bricks by hand. The same technology that lets it finish a full-size house in a single day is now being studied as a way to fabricate shelters on the Moon, using local rock instead of concrete.

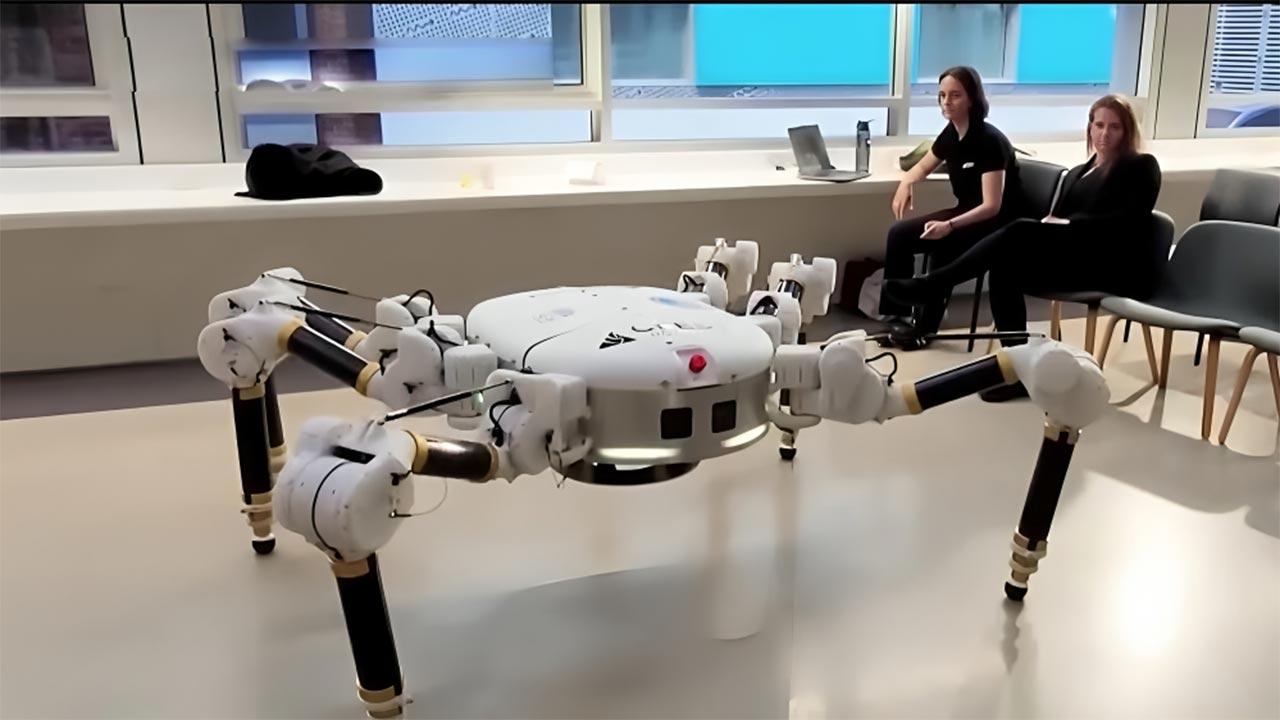

The machine is called Charlotte, and its creators see it as a bridge between terrestrial building and off-world infrastructure, a platform that can scale from suburban lots to lunar lava tubes. If that vision holds, the first permanent neighborhoods on another world may not be assembled by astronauts with tool belts, but printed layer by layer by an autonomous robot that moves like a giant mechanical spider.

From Australian jobsite to off-world testbed

Charlotte began as a solution to a very Earth-bound problem, namely how to build houses faster, cheaper, and with less waste than conventional construction allows. The robot is designed to 3D print the structural shell of a home of about 2,150 square feet in roughly 24 hours, turning a process that usually takes weeks into a single continuous print run that can be paused and resumed as needed. Its developers frame it as a response to housing shortages and labor constraints, with automation handling the repetitive, heavy work while human crews focus on finishing and services.

Instead of being bolted to a gantry or confined to a fixed frame, Charlotte moves on multiple articulated legs, carrying its print head wherever the digital blueprint requires. That mobility lets it trace out curved walls, internal partitions, and complex footprints without reconfiguring scaffolding or rails, a capability that has been highlighted in detailed walk-throughs of the system’s operation in demonstration footage. The same freedom of movement that makes it attractive on uneven building sites is what has caught the attention of engineers thinking about how to operate on the far rougher terrain of the lunar surface.

How Charlotte actually prints a house in a day

At the core of Charlotte’s appeal is speed, and that speed comes from treating a house not as a set of discrete components but as a continuous printed object. The robot follows a pre-programmed path, extruding a proprietary cement-like mix in steady beads that stack into walls, with the nozzle adjusting height and flow rate to maintain consistent layer thickness. By keeping the print head in motion almost constantly, the system can complete the load-bearing envelope of a 2,150 square foot home in about one day of operation, a figure that has been emphasized in coverage of the 24-hour build capability.

The material itself is engineered to set quickly enough that new layers do not slump, but slowly enough to allow bonding between passes, a balance that is crucial when the robot is looping around a site at speed. Reports on Charlotte’s development describe a mix that incorporates sustainable ingredients and industrial byproducts, reducing reliance on traditional Portland cement and lowering the embodied carbon of each print. That combination of rapid deposition and tailored material behavior is what makes the one-day build more than a publicity stunt, turning it into a repeatable process that can be adapted to different floor plans and climates.

Why a spider-like robot beats a fixed printer

Most early 3D-printed buildings relied on gantry systems or robotic arms anchored to a foundation, which limited the size and shape of what could be built. Charlotte’s spider-like form factor is a deliberate break from that model, using multiple legs to clamber around a site and reposition its print head without disassembly. This approach lets it negotiate slopes, step over low obstacles, and work on irregular plots that would be difficult to span with a rigid frame, a flexibility that has been underscored in technical profiles of the multi-legged platform.

The robot’s gait is coordinated with its extrusion system so that each movement supports the integrity of the print, with sensors monitoring position and orientation to keep the nozzle aligned with the digital model. That coordination is particularly important when printing curved or non-orthogonal walls, where small deviations can accumulate into visible defects. Video segments showing Charlotte in action highlight how the machine can pivot around corners, adjust its stance, and resume printing from different angles without losing registration, a capability that has been explored in depth in broadcast coverage of its test builds.

Inside the material mix and structural design

Speed and mobility would mean little if the printed structures could not stand up to real-world loads, so Charlotte’s creators have invested heavily in the chemistry and geometry of the walls it produces. The printable mix is formulated to flow smoothly through the nozzle while maintaining enough body to hold shape, with additives that control setting time, shrinkage, and long-term durability. Reports on the system describe a focus on sustainable binders and aggregates, positioning the material as both structurally robust and less carbon-intensive than conventional concrete, a balance that has been examined in analyses of how 3D-printed construction can reduce waste.

Structurally, the printed walls often use hollow or ribbed cross-sections, which reduce material use while preserving strength, and can be filled or insulated after printing depending on climate requirements. The robot’s ability to vary wall thickness and internal patterns on the fly allows engineers to reinforce specific zones, such as around openings or at load transfer points, without changing the overall construction method. Detailed breakdowns of Charlotte’s output show how these parametric wall designs can be tuned for different codes and performance targets, with the robot adjusting its toolpath to embed reinforcement or conduits where needed, a level of control that has been highlighted in technical explainers on the printing process.

Economic stakes: housing, labor, and cost curves

The promise of a robot that can print a full-size home in 24 hours is not just a technological curiosity, it is a direct challenge to the economics of traditional building. By compressing the structural phase of construction into a single day, Charlotte can reduce labor hours on site, cut down on scheduling delays, and limit exposure to weather-related disruptions. Analyses of the system’s potential impact point to lower per-unit costs for the shell of a house, especially when the robot can be kept in near-continuous operation across multiple sites, a scenario explored in reporting on how 24-hour printing could reshape project timelines.

There are also implications for the construction workforce, which is already grappling with shortages in many regions. Advocates for robotic printing argue that systems like Charlotte can take on the most physically demanding and repetitive tasks, reducing injury risk and opening the field to a broader range of workers focused on design, supervision, and finishing trades. Critics worry about displacement of traditional roles, but the early deployments described in coverage of Charlotte’s test projects emphasize hybrid teams, where human crews handle foundations, services, and interiors while the robot manages the shell. That division of labor could, in practice, shift the industry toward higher-skilled, better-paid roles if training and policy keep pace.

Why lunar engineers are paying attention

The same traits that make Charlotte attractive on Earth, mobility, autonomy, and the ability to print large structures quickly, map neatly onto the challenges of building on the Moon. Any lunar construction system must cope with extreme temperature swings, abrasive dust, and the high cost of transporting materials from Earth, which is why engineers are focused on using local regolith as feedstock. Reports on Charlotte’s potential off-world applications describe research into adapting its extrusion system to handle regolith-based mixes, turning crushed lunar rock into a printable material that can form radiation-shielding walls and protective berms, a concept that has been explored in depth in coverage of how a spider robot could 3D print on the Moon.

Autonomy is another critical factor, since early lunar bases will have limited human presence and tight crew time budgets. Charlotte’s control software is already designed to follow complex toolpaths with minimal intervention, and the system’s sensor suite can be expanded to include more robust localization and hazard detection for off-world use. Analysts looking at lunar mission architectures have pointed to the advantage of sending construction robots ahead of crewed landings, allowing them to print landing pads, shelters, and storage vaults in advance. In that scenario, a Charlotte-derived platform could arrive on a cargo lander, deploy itself, and begin printing structures using regolith processed by companion systems, reducing the mass that needs to be launched from Earth.

Adapting Charlotte for lunar regolith and low gravity

Translating a terrestrial construction robot to the Moon is not a simple copy-and-paste exercise, and engineers studying Charlotte’s design have been explicit about the modifications required. The material system is the most obvious change, since the current cementitious mix relies on water and binders that are not readily available on the lunar surface. Research efforts described in technical reporting focus on sintering or binding regolith using minimal imported additives, potentially with microwave or laser assistance, and then feeding that processed material into an extrusion head adapted from Charlotte’s existing hardware, a pathway that has been outlined in discussions of how the robot might handle lunar regolith.

Low gravity and vacuum conditions also affect how a multi-legged robot moves and stabilizes itself, especially while carrying a heavy print head and material lines. Engineers anticipate redesigning the legs with wider contact patches and possibly anchoring mechanisms to prevent slipping on loose regolith, while also hardening joints and electronics against dust infiltration. Thermal control becomes more complex without an atmosphere, so any lunar variant would need insulated housings and radiators tuned to the harsh day-night cycle. These adaptations are not trivial, but they build on the same core idea that underpins Charlotte on Earth, a mobile platform that can position a print head anywhere within a large, unstructured worksite and execute a digital blueprint with high precision.

From concept videos to field trials and policy debates

Public awareness of Charlotte has grown through a mix of on-site demonstrations, technical briefings, and widely shared video segments that show the robot in motion around partially printed homes. These clips have helped demystify the technology, showing how the machine navigates, extrudes material, and coordinates with human workers on the ground. One widely circulated segment follows the robot through a full build cycle, from initial calibration to the final wall layers, illustrating how the process compresses what would normally be a multi-week schedule into a single continuous operation, as seen in broadcast-style coverage of its Earth and Moon potential.

As the technology moves from pilot projects toward broader deployment, regulators and policymakers are beginning to grapple with questions around building codes, safety standards, and workforce impacts. Construction codes in many jurisdictions were written with conventional materials and methods in mind, so certifying 3D-printed walls and novel geometries requires new testing protocols and design guidelines. At the same time, labor organizations and training providers are looking at how to prepare workers for roles in robotic construction, from operating and maintaining machines like Charlotte to integrating printed shells with traditional trades. The policy conversation is still in its early stages, but the trajectory of field trials and public demonstrations suggests that these questions will move from theoretical to urgent as more projects adopt robotic printing.

The road from suburban lots to lunar bases

Charlotte’s evolution from an Australian construction experiment to a candidate for lunar infrastructure captures a broader shift in how robotics and additive manufacturing are converging. On Earth, the robot is framed as a tool to tackle housing shortages, reduce waste, and make construction sites safer, with its 24-hour build capability and spider-like mobility serving as tangible proof points. Off-world, the same underlying architecture is being reimagined as a way to turn alien landscapes into habitable outposts, using local materials and autonomous operation to sidestep the logistical limits of human-led building. Analysts who have followed the project’s trajectory argue that this dual-use potential is not a coincidence but a reflection of how frontier technologies often find their first footholds in extreme environments before reshaping everyday life.

For now, Charlotte’s most concrete achievements are still on Earth, where printed walls rise on suburban lots and test sites rather than in lunar craters. Yet the fact that engineers and space agencies are already studying how to adapt its design for regolith, low gravity, and vacuum conditions shows how quickly the conversation has expanded. In that sense, every new house the robot prints is also a rehearsal for something more ambitious, a proof that complex, load-bearing structures can be extruded by a mobile machine following a digital script. Whether or not Charlotte itself ever crawls across the Moon, the ideas it embodies are likely to shape the first generation of off-world builders, and the footage of its early trials, captured in detailed construction walk-throughs, may one day look like the Wright Flyer of extraterrestrial architecture.

More from MorningOverview