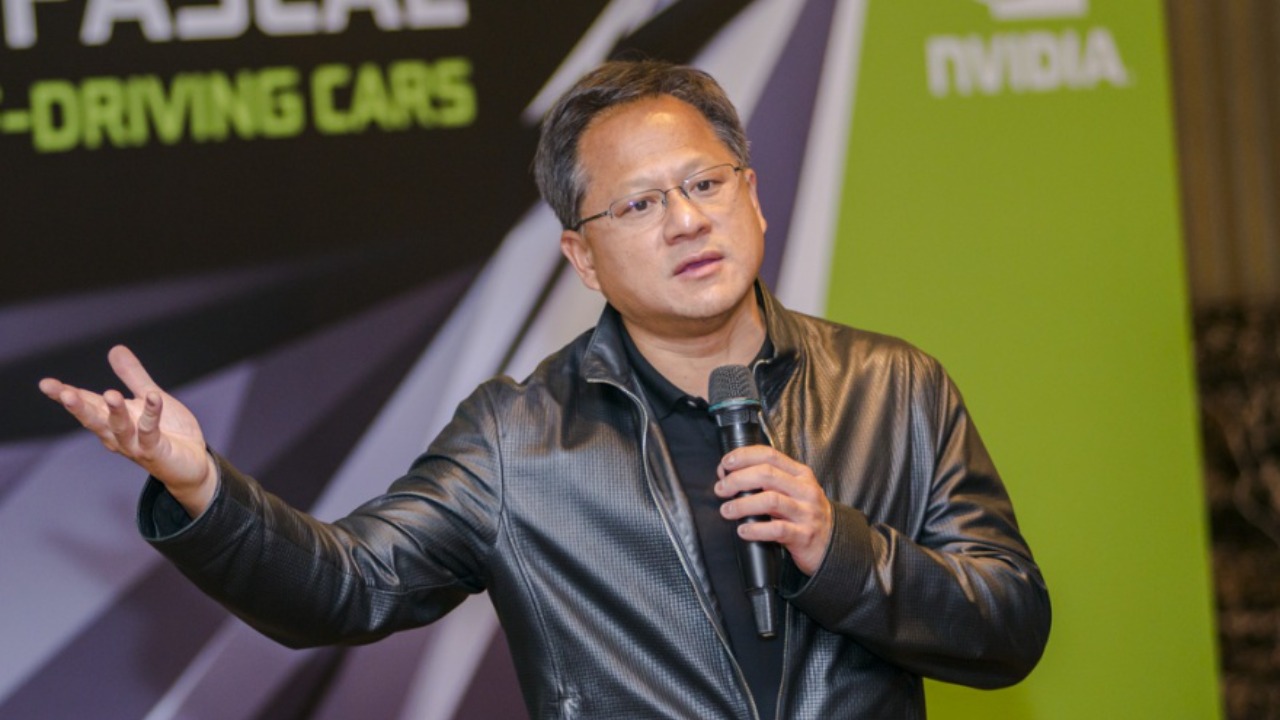

Artificial intelligence is often sold as a shortcut to an easier workday, but Nvidia chief executive Jensen Huang is arguing the opposite. In his view, the real impact of generative tools will be to strip away excuses, raise expectations, and push knowledge workers to produce far more than they do today. Instead of promising a future of leisure, he is telling his own employees, and anyone listening, to prepare for a world where AI turns every job into a higher‑pressure performance test.

That message lands differently from the usual corporate optimism about “productivity gains,” because it treats AI less as a labor saver and more as a force multiplier for ambition. When the person running the world’s most valuable chip company says the technology will make people work harder, not less, he is signaling a shift in how power, responsibility, and opportunity will be distributed inside offices and across the broader economy.

Huang’s blunt message: AI is here to raise the bar, not lower it

Jensen Huang has been unusually direct about what he expects AI to do to white‑collar work, and comfort is not on the list. In internal and public remarks, he has argued that once everyone has access to powerful assistants, the baseline for what counts as “good enough” output will jump, and managers will judge people against that new standard rather than the old one. Instead of imagining AI as a way to clock out early, he describes it as a tool that will expose who can leverage automation to deliver more, faster, and with fewer excuses, a framing that has already sparked debate among technologists and office workers who had hoped for the opposite effect, as reflected in coverage of his view that AI will actually make people work harder.

That stance fits with Huang’s broader belief that generative models are now a core part of professional competence, not a side experiment. He has suggested that in a world where drafting a report, debugging code, or preparing a slide deck can be accelerated by an assistant, the people who still take days to do what others can finish in hours will be seen as falling behind. The implication is that AI will not just change tools, it will reshape expectations about pace, responsiveness, and even creativity, because the baseline level of polish that a machine can provide will become the minimum acceptable standard rather than a nice‑to‑have flourish.

Inside Nvidia: a mandate to use AI on “every task possible”

Huang is not keeping this philosophy at the level of conference‑stage rhetoric, he is turning it into a management directive inside Nvidia. According to accounts of his internal guidance, he has told staff that they are expected to run their work through AI systems whenever it makes sense, from drafting emails to exploring design options, and that failing to do so will eventually look like ignoring a core part of the company’s toolkit. That expectation has been described as a push for employees to apply AI to every task possible, a phrase that captures how deeply he wants the technology woven into daily routines rather than reserved for special projects.

Inside a company that builds the GPUs powering most large AI models, this is also a cultural signal about what counts as professionalism. By insisting that engineers, marketers, and managers all treat AI as a default companion, Huang is effectively saying that fluency with these tools is now as basic as knowing how to use email or spreadsheets. That expectation is reinforced by reports that he has personally urged Nvidia employees to embrace AI in their workflows, with internal communications highlighting how he told employees to lean on the technology rather than treat it as an optional experiment.

“Are you insane?”: Huang’s impatience with AI‑skeptical managers

Huang’s push for universal AI adoption has also come with sharp criticism for anyone inside Nvidia who tries to slow it down. In one widely cited exchange, he reportedly reacted with disbelief to managers who were advising their teams to limit AI use, asking them, “Are you insane?” and making clear that he sees such caution as a competitive liability rather than prudent risk management. That remark, relayed in coverage of his comments to internal leaders, underscores how strongly he opposes directives that tell people to use less AI at a moment when he believes rivals are racing to integrate more.

From a worker’s perspective, that kind of language sends a clear message about where power lies in the AI transition. If a senior executive is willing to publicly ridicule managers who urge restraint, then employees who are uneasy about privacy, bias, or job security have little institutional cover to slow down. The cultural norm becomes “use AI first, ask questions later,” and anyone who hesitates risks being labeled as resistant to change. That dynamic helps explain why Huang’s comments have resonated far beyond Nvidia, because they crystallize a broader shift in corporate culture where skepticism about automation is increasingly framed as irrational rather than cautious.

AI as a “co‑pilot” that quietly doubles the workload

Publicly, Huang often describes AI as a co‑pilot, a metaphor that sounds collaborative but also implies that the human remains responsible for the flight. In practice, that framing can translate into more work, not less, because the person in the cockpit is now expected to oversee both their own judgment and the machine’s suggestions. Instead of replacing tasks, AI tools often create new layers of review, experimentation, and iteration, which can stretch the workday even as they speed up individual steps. Huang has leaned into this idea in interviews and talks, including a widely shared video appearance where he outlines his belief that AI will augment human capability rather than render people obsolete.

That co‑pilot framing also helps explain why he thinks productivity gains will translate into higher expectations rather than shorter hours. If a marketing manager can now generate ten campaign concepts in the time it once took to draft one, the likely outcome is not that they go home early, but that leadership expects them to test and refine more options. The same logic applies to software engineers who can use code assistants to explore multiple implementations or to analysts who can ask large language models to slice data in dozens of ways. Huang’s message is that AI will expand the scope of what is possible within a given workday, and companies will quickly treat that expanded scope as the new normal.

“Everyone a programmer”: how Huang sees jobs evolving

Huang has also advanced a specific vision of how AI will reshape skill sets, arguing that generative tools will effectively turn many knowledge workers into software creators, whether they think of themselves that way or not. In his telling, natural language interfaces will let people describe what they want a system to do, and the AI will handle the coding, which means the boundary between “technical” and “non‑technical” roles will blur. That idea, that AI will make everyone a programmer, is central to his optimism about job growth, because it suggests that people who were previously locked out of software development can now participate in building and customizing digital tools.

At the same time, this vision raises the bar for what counts as basic literacy in the workplace. If describing workflows to an AI becomes as routine as writing an email, then employees who cannot structure their requests clearly or reason about logic will be at a disadvantage. Huang has framed this shift as an opportunity for workers to climb the value chain, but it also implies a sorting effect, where those who adapt quickly to prompt‑driven interfaces and automated coding will be able to take on more complex responsibilities, while others may find that their existing tasks are easier to automate away.

Entry‑level anxiety: what happens to junior roles

One of the sharpest tensions in Huang’s argument is around entry‑level work. On the one hand, he has suggested that AI will create new categories of jobs and expand demand for people who can guide and supervise models. On the other, the same tools are already being used to automate many of the tasks that used to be assigned to interns and junior staff, from drafting basic reports to cleaning data. Reporting on his recent comments has highlighted this contradiction, noting that he sees AI as a driver of jobs growth even as questions mount about how newcomers will gain experience in a world where machines handle much of the grunt work.

For young workers, that dynamic can feel like a trap. If AI tools are good enough to handle the routine tasks that once served as training grounds, then companies may expect new hires to arrive already capable of higher‑level judgment, even though they have had fewer chances to practice. Huang’s insistence that AI will raise expectations rather than lower them intensifies that pressure, because it suggests that entry‑level employees will be judged not only on their raw potential but also on how effectively they can orchestrate automated systems. The risk is that a generation of workers is asked to skip the apprenticeship phase and jump straight into roles that require both domain expertise and AI fluency.

How Nvidia’s internal culture is becoming a template

Because Nvidia sits at the center of the AI hardware boom, its internal norms are likely to influence how other companies think about adoption. Accounts of the firm’s culture describe a workplace where employees are encouraged to experiment aggressively with generative tools, share prompts, and build custom assistants for their teams, all under the implicit expectation that those who do not keep up will be left behind. One detailed look at this environment noted how Huang has pushed staff to treat AI as a default part of their workflow, with internal stories about how Nvidia employees are using the technology to accelerate everything from chip design to HR processes.

That culture is already spilling outward as clients, partners, and competitors study Nvidia’s practices for clues about how to organize their own AI transitions. If the company that sells the picks and shovels of the AI gold rush is telling its people to automate aggressively and accept higher workloads as the price of staying ahead, other firms may feel pressure to adopt similar expectations. In that sense, Huang’s comments are not just internal guidance, they are a kind of industry benchmark, signaling that in the race to harness generative tools, the winners will be those who are willing to let AI reshape job descriptions, performance metrics, and even the pace of decision‑making.

Public reaction: enthusiasm, skepticism, and worker pushback

Outside Nvidia, Huang’s insistence that AI will make people work harder has sparked a mix of admiration and unease. Some technologists and entrepreneurs see his stance as refreshingly honest, a recognition that productivity tools rarely translate into shorter workweeks in competitive industries. Others, including many rank‑and‑file employees in tech and beyond, worry that executives are using AI as a pretext to demand more output without offering corresponding increases in pay, autonomy, or job security. That tension is visible in online discussions where users dissect his remarks, including threads on r/artificial that debate whether his “everyone a programmer” vision is empowering or simply a way to justify higher expectations.

These reactions highlight a broader question about who will capture the value created by AI‑driven productivity gains. If tools make it easier to produce more code, content, or analysis in less time, companies can respond in several ways: they can reduce headcount, keep staffing levels constant while increasing output, or share the benefits with workers through shorter hours or higher pay. Huang’s rhetoric so far has focused on the second path, emphasizing growth and competitiveness rather than redistribution. That emphasis helps explain why his comments have become a flashpoint in debates about the future of work, because they crystallize a fear that AI will intensify existing pressures rather than alleviate them.

The soundbite era: how short clips shape the AI work narrative

Huang’s views are not just traveling through long interviews and internal memos, they are also being distilled into viral soundbites that shape public perception. Short clips of him talking about AI’s impact on jobs, often edited for maximum punch, circulate widely on social platforms, where they are interpreted and reinterpreted by audiences far beyond the tech industry. One such short video captures his insistence that people must adapt quickly to AI or risk being left behind, a message that resonates with some viewers as a call to action and with others as a threat.

These snippets can flatten nuance, but they also reveal what parts of his message are sticking. Phrases about working harder, becoming programmers, or being “insane” to avoid AI are easy to clip and share, and they reinforce a narrative in which the future of work is a high‑stakes race rather than a negotiated transition. For workers trying to make sense of how AI will affect their own jobs, those soundbites can feel like marching orders from the top of the tech hierarchy, even if the underlying reality is more complex and varies widely by industry, role, and geography.

What Huang’s vision means for the next phase of office work

Taken together, Huang’s comments sketch a future in which AI is woven into nearly every white‑collar task, from the most mundane to the most strategic, and in which the primary effect is to compress timelines and expand expectations. In that world, success depends less on whether someone uses AI at all and more on how creatively and responsibly they orchestrate it, juggling speed with oversight and automation with judgment. His insistence that AI will make people work harder is not a prediction of universal burnout so much as a warning that the competitive bar is about to rise, and that those who treat generative tools as optional will find themselves outpaced by colleagues who do not.

For workers and managers, the challenge is to decide how to respond to that pressure. One path is to accept Huang’s framing and race to match Nvidia’s intensity, embedding AI into every process and measuring people by how much more they can produce. Another is to push for a different social contract around automation, one that treats productivity gains as a chance to rebalance workloads, invest in training, and protect time for deep, non‑automated thinking. Huang has made his preference clear in interviews and appearances, including the high‑profile discussion of harder work that helped ignite this debate, but the ultimate shape of the AI workplace will depend on how companies, workers, and policymakers choose to interpret and act on that message.

More from MorningOverview