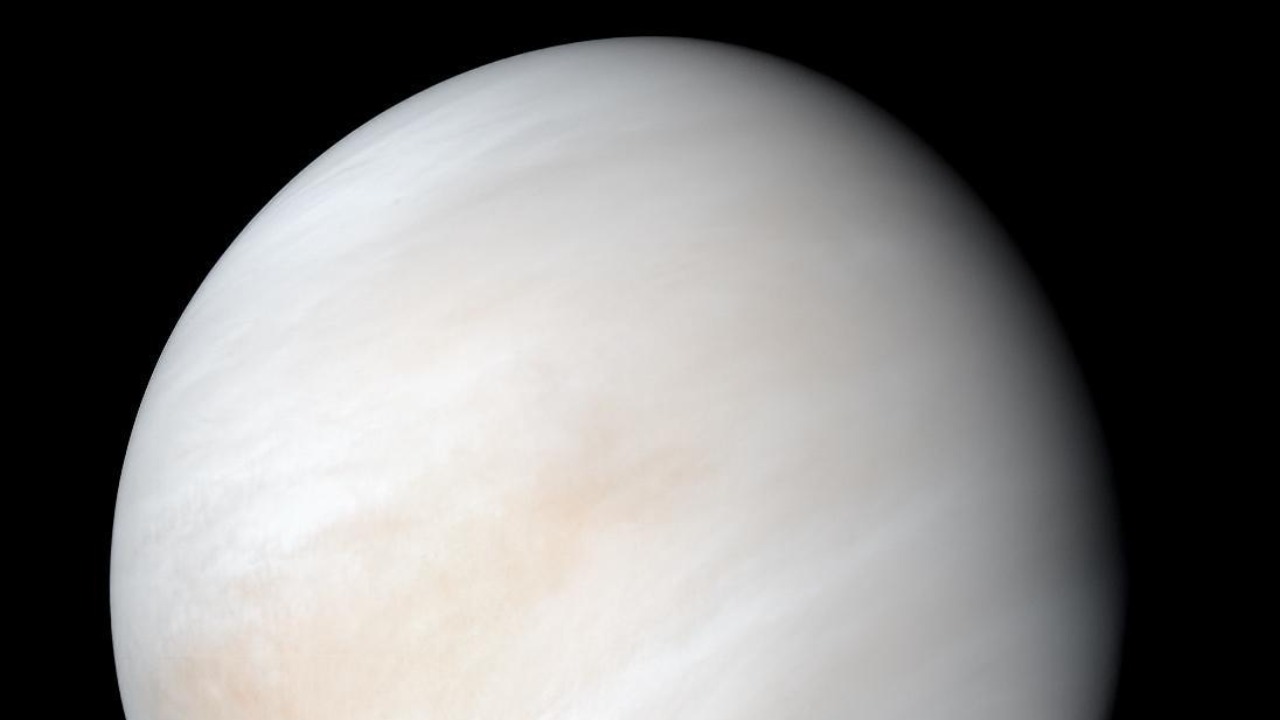

Venus spins slowly, yet its upper atmosphere races around the planet at roughly 220 miles per hour, a supercharged jet stream that has puzzled scientists for decades. Now a new line of research argues that a subtle interplay of sunlight, chemistry, and planetary rotation may finally explain how those winds are born and why they keep accelerating. I want to walk through what that proposed solution looks like, how it fits with earlier measurements, and why it matters for understanding not just Venus, but extreme climates across the solar system.

Why Venus’s atmosphere is so baffling

Venus should be a sluggish world. It rotates so slowly that a single day there lasts longer than its year, yet the air high above its surface laps the planet in just a few Earth days, a phenomenon scientists call superrotation. The contrast between the planet’s lethargic spin and its hyperactive atmosphere is so stark that for years it has been one of the central unsolved problems in planetary science, especially once probes confirmed that the winds in the cloud tops routinely reach about 220 miles per hour, far beyond typical hurricane speeds on Earth.

What makes the puzzle deeper is that these winds do not simply circle at a steady pace, they appear to strengthen with altitude and vary over time in ways that early models struggled to reproduce. Observations from orbiting spacecraft and ground based telescopes showed that the atmosphere’s rotation can speed up or slow down over periods of years, even as the planet’s solid body remains almost unchanged, a disconnect that left researchers searching for a mechanism that could pump energy into the air and keep it racing around the planet. That search has driven a series of missions and analyses that culminate in the latest attempt to identify the true engine of Venus’s superrotation.

How we first measured 220 mph winds on a slow-spinning world

The story of those 220 mile per hour winds begins with the first detailed cloud tracking campaigns, when scientists used ultraviolet images to follow bright and dark patterns as they drifted across the planet’s disk. By comparing how fast those features moved relative to the surface, researchers realized that the atmosphere at the cloud tops was circling Venus in just a few days, implying wind speeds that rival the most intense storms on Earth. Later spacecraft refined those estimates, confirming that the upper atmosphere behaves like a continuous global hurricane wrapped around the planet, with speeds that can exceed 100 meters per second in the equatorial regions according to detailed wind measurements.

Those early measurements also revealed that the winds are not uniform from top to bottom. At lower altitudes, closer to the crushing surface pressure, the air moves more slowly, while the fastest flows sit near the cloud tops where solar heating is strongest. Over time, missions such as Venus Express and ground based campaigns built up a record showing that the superrotation can wax and wane, with the atmosphere sometimes speeding up by tens of meters per second over a few years. That variability hinted that the winds are not just a passive response to the planet’s rotation, but the product of a dynamic energy cycle that needed to be identified and quantified.

The new explanation: sunlight, chemistry, and a hidden engine

The latest research argues that the key to Venus’s extreme winds lies in how sunlight interacts with its thick, sulfuric acid clouds and carbon dioxide rich air. Instead of a simple picture where heat flows from the dayside to the nightside and drives a global breeze, the new work suggests that subtle temperature contrasts and chemical reactions in the upper atmosphere create waves and instabilities that feed momentum into the jet stream. In this view, the superrotation is not a single monolithic current, but the emergent result of countless small pushes from thermal tides and gravity waves that are constantly generated as the atmosphere absorbs and re radiates solar energy.

By combining high resolution simulations with constraints from spacecraft data, the researchers propose that these waves can transport angular momentum upward and toward the equator, effectively spinning up the upper atmosphere relative to the surface. That mechanism helps explain why the winds peak near the cloud tops and why they can maintain such high speeds despite friction and radiative cooling. It also offers a way to reconcile the observed variability, since changes in cloud opacity or solar input could modulate how efficiently the waves pump energy into the flow, a pattern that aligns with the evolving wind speeds reported in long term monitoring campaigns and in recent analyses of what drives Venus’s winds.

What earlier missions already hinted about superrotation

Long before this new model was proposed, spacecraft had been quietly collecting clues that Venus’s atmosphere is shaped by complex waves and tides rather than a simple day night circulation. Ultraviolet images revealed large scale patterns that looked like planetary waves, while infrared observations showed temperature structures that could only be explained if heat was being redistributed by more than just straightforward convection. Some of the most striking evidence came from orbiters that watched the cloud tops brighten and dim in repeating patterns, a sign that atmospheric tides driven by the planet’s slow rotation and intense solar heating were at work.

Those missions also documented how the winds change with latitude and altitude, building a three dimensional picture that any successful theory would have to match. Measurements showed that the superrotation is strongest near the equator and weakens toward the poles, and that the vertical wind profile is shaped by the dense lower atmosphere and the radiatively active cloud deck above. When researchers fed those constraints into general circulation models, they found that including thermal tides and gravity waves made it easier to reproduce the observed wind speeds, a result that set the stage for the more detailed wave driven explanations now being advanced and echoed in coverage that describes how Venus’s howling winds strengthen with height.

How the new model “cracks the code” of Venus’s winds

The new work builds on that foundation by treating Venus’s atmosphere as a coupled system where waves, tides, and mean flows constantly exchange energy and momentum. In the simulations, solar heating of the thick cloud layer generates thermal tides that propagate around the planet, while topography and convection launch gravity waves that travel upward from the lower atmosphere. As these waves break or dissipate, they deposit momentum into the background flow, preferentially accelerating air in the direction of the planet’s rotation and amplifying the superrotation at the cloud tops.

What makes this approach compelling is that it can reproduce both the magnitude and the structure of the observed winds without resorting to ad hoc assumptions. The model naturally produces a jet that circles the planet in a few days, with peak speeds near 220 miles per hour and a vertical profile that matches spacecraft data, while also allowing for multi year variations as the wave activity waxes and wanes. That success has led some researchers to argue that the long standing mystery of Venus’s winds is finally close to resolution, a sentiment reflected in recent reports that scientists may have cracked the code of the 220 mph winds by focusing on the cumulative effect of these atmospheric waves.

Independent evidence from “planetary storm chasers”

While models are essential, they only gain credibility when they line up with independent observations, and that is where a new generation of so called planetary storm chasers comes in. By stitching together images from multiple spacecraft and Earth based telescopes, these teams have been able to track individual cloud features over long periods, effectively watching the same parcels of air race around the planet. Their reconstructions show that the winds can surge and slacken in ways that match the kind of variability predicted by wave driven superrotation, lending weight to the idea that the atmosphere’s behavior is governed by a delicate balance of wave forcing and radiative damping.

Some of these studies have focused on how the winds respond to changes in solar input and cloud structure, looking for correlations that would support the role of thermal tides. Others have examined the fine scale ripples and streaks in the clouds, which are signatures of gravity waves propagating through the atmosphere. Together, they paint a picture of a dynamic, constantly perturbed system where waves are not a minor detail but a central driver of the global circulation, a view that aligns with recent analyses of new findings about Venus wind speeds that emphasize the importance of high cadence, long baseline tracking of atmospheric features.

What Venus’s winds reveal about the planet’s past

Understanding how Venus’s atmosphere moves today is not just an exercise in fluid dynamics, it also offers clues about how the planet evolved from a potentially more temperate world to the hothouse we see now. If superrotation is sustained by the current balance of solar heating, cloud chemistry, and planetary rotation, then changes in any of those factors over time could have altered the strength and structure of the winds. For example, shifts in the composition or thickness of the cloud deck would change how sunlight is absorbed and re emitted, which in turn would affect the generation of thermal tides and gravity waves that feed the jet.

Recent work on the planet’s geological and atmospheric history suggests that Venus may once have had very different surface conditions, possibly including liquid water, before a runaway greenhouse effect transformed it into a world with surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead. If that is the case, then the onset of superrotation at the current intensity might be tied to that climatic transition, with the present day winds acting as a kind of fossil record of the processes that drove the atmosphere into its current state. That perspective is reflected in new research that treats the planet’s violent present as a clue to its mysterious past, linking present day atmospheric dynamics to long term planetary evolution.

Why Venus matters for exoplanets and extreme climates

Cracking the physics behind Venus’s 220 mile per hour winds has implications far beyond our neighboring planet. Many of the exoplanets discovered in recent years orbit close to their stars and are expected to be tidally locked, with permanent day and night sides that could foster strong atmospheric superrotation. If wave driven mechanisms can sustain such flows on Venus, then similar processes may be at work on those distant worlds, shaping their climate patterns, cloud distributions, and even their potential habitability. In that sense, Venus serves as a nearby laboratory for testing ideas that will eventually be applied to planets we can only study as faint points of light.

The lessons from Venus also feed back into our understanding of extreme weather and climate on Earth, even if the scales are very different. The same basic physics of waves, tides, and jet streams operates in our own atmosphere, where gravity waves generated by mountains and storms can influence the polar vortex and the distribution of ozone. By studying a world where those processes are pushed to their limits, researchers can refine the models that predict how jet streams respond to changes in heating and composition, insights that are relevant for everything from long range weather forecasting to projections of how Earth’s circulation might shift as greenhouse gas concentrations rise.

How classic Venus research set the stage

The current wave focused explanation for Venus’s winds did not emerge in a vacuum, it rests on decades of theoretical and observational work that tried to reconcile the planet’s slow rotation with its fast moving atmosphere. Early studies of superrotation explored a range of mechanisms, from large scale eddies to barotropic instabilities, and gradually converged on the idea that some form of wave momentum transport was essential. Those efforts produced a body of literature that mapped out the parameter space of possible solutions and identified which combinations of heating, rotation, and friction could sustain a jet that outruns the solid planet.

Many of the mathematical tools and conceptual frameworks used today trace back to those foundational analyses, which laid out the equations governing angular momentum budgets and wave mean flow interactions in a rotating atmosphere. By revisiting those classic models with modern computational power and updated observational constraints, researchers have been able to test more realistic scenarios and explore how different types of waves contribute to the overall circulation. That continuity is evident in technical references that compile the state of knowledge on Venus’s atmosphere and superrotation, showing how the field has moved from broad theoretical sketches to detailed, data driven simulations.

From planetary winds to everyday risk: why speed and scale matter

When I think about Venus’s 220 mile per hour winds, I am struck by how our intuition about speed breaks down once we leave the familiar context of Earth’s weather. On our planet, a Category 5 hurricane with sustained winds above 157 miles per hour is enough to flatten neighborhoods and strip trees bare, yet on Venus, even higher speeds are part of the background state of the upper atmosphere. The difference lies not only in the absolute numbers, but in the density of the air, the vertical structure of the atmosphere, and the way energy is distributed across scales, factors that determine whether a given wind speed translates into destructive force at the surface.

That distinction matters when we try to connect planetary science to everyday experience, including how we think about risk from wind and traffic in our own cities. On Earth, the kinetic energy of moving air and vehicles is what makes high speeds dangerous, whether it is a storm surge or a car traveling too fast through a crosswalk. The same basic physics that lets us calculate the momentum of Venus’s superrotating atmosphere also underpins the design of safer streets, where reducing speed can dramatically cut the severity of collisions involving people on foot or on bikes, a principle that guides efforts to improve bicyclist and pedestrian safety in urban environments.

What comes next for Venus wind science

The proposed solution to Venus’s wind mystery is compelling, but it is not the final word, and the next decade of exploration will be crucial for testing its predictions. Upcoming missions plan to send new orbiters and possibly probes into the planet’s atmosphere, where they can directly measure temperature, wind speed, and wave activity at multiple altitudes. Those data will help determine how much momentum is really being transported by thermal tides and gravity waves, and whether the balance of forces in the models matches the reality of a churning, cloud shrouded sky. If the observations line up, the wave driven superrotation framework will gain strong support, and if they do not, researchers will have to refine or rethink key parts of the theory.

In the meantime, scientists are already mining existing datasets with fresh techniques, using machine learning and advanced image processing to track ever smaller features in the clouds and to tease out subtle patterns in the winds. Some of that work involves reanalyzing historical records and code repositories that document how earlier teams processed Venus images and derived wind fields, including open resources such as a publicly shared analysis script that illustrates the kind of computational tools used to extract motion from planetary images. As those methods improve, they will sharpen our view of how the atmosphere behaves from hour to hour and year to year, providing an ever more stringent test of the idea that a symphony of waves is what keeps Venus’s winds racing at 220 miles per hour.

Why the mystery is closer to solved, but not closed

After decades of puzzling over how a planet that spins so slowly can host such ferocious winds, the scientific community now has a coherent, physically grounded explanation that ties together observations, theory, and simulation. The idea that solar driven tides and gravity waves can pump angular momentum into the upper atmosphere, sustaining a global jet that outruns the solid planet, fits the available data and reproduces the key features of the circulation. It also connects Venus to a broader class of superrotating atmospheres, from tidally locked exoplanets to certain regimes in Earth’s own stratosphere, giving the solution a reach that extends well beyond a single world.

At the same time, important questions remain open, including how the strength of the superrotation has changed over Venus’s history, how it interacts with the planet’s chemistry and cloud microphysics, and whether there are feedbacks that could tip the atmosphere into different states. Those uncertainties are not a weakness of the current explanation, but a reminder that even when a central mechanism is identified, the full story of a planet’s climate is always richer and more intricate than any single model can capture. For now, though, the long standing mystery of Venus’s 220 mile per hour winds looks less like an unsolved riddle and more like a complex, but increasingly well understood, consequence of how light, air, and rotation conspire on one of the most extreme worlds in the solar system.

More from MorningOverview