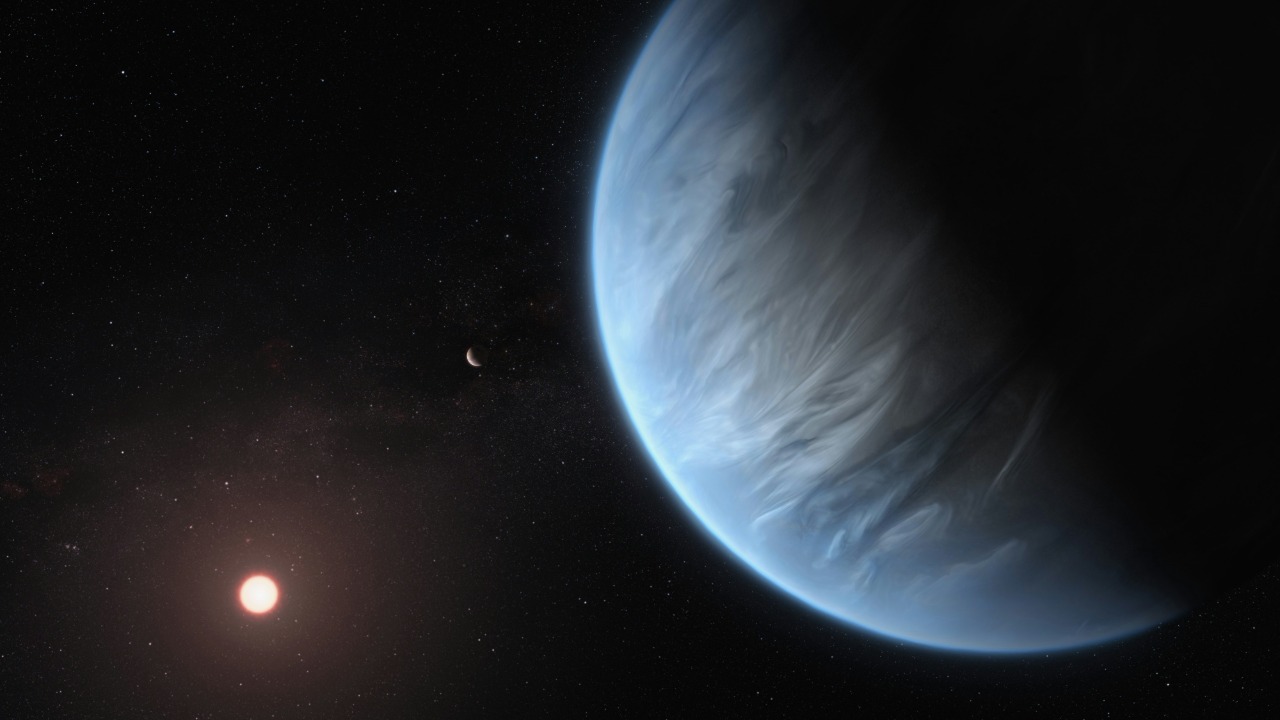

For decades, the search for alien life has revolved around a narrow ring around stars where liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface. That “habitable zone” remains important, but astronomers are now finding that the real clues may lie in the skies of worlds that sit well inside or far outside that comfortable band. By decoding exoplanet atmospheres, even on planets that look hostile at first glance, I can trace how energy, chemistry, and climate interact to create or crush the conditions life needs.

Instead of treating distant planets as static dots, researchers are beginning to read them as dynamic worlds whose gases, clouds, and temperatures record their histories. That shift is turning some previously overlooked targets into prime laboratories for understanding how life might adapt to extremes, and it is reshaping how telescopes are tasked, how models are built, and how we define what a “potentially habitable” planet really is.

Why atmospheres matter more than a simple habitable zone map

The classic habitable zone is a useful starting point, but it hides a messy reality. Two planets at the same distance from a star can have wildly different surface conditions depending on how thick their atmospheres are, what gases dominate, and how efficiently they trap heat. A dense blanket of carbon dioxide can keep a world warm far beyond the textbook habitable zone, while a thin or eroded atmosphere can leave a closer-in planet frozen or scorched despite receiving the “right” amount of starlight.

That is why many astronomers now argue that the next breakthroughs will come from treating atmospheres as the primary filter for habitability, not just the orbital sweet spot. Detailed discussions of exoplanet climate show how greenhouse gases, cloud layers, and circulation patterns can extend or shrink the region where liquid water is stable, even for planets that orbit red dwarfs or more active stars, and those insights are driving new observing strategies that look well beyond the traditional habitable zone map.

Reading life’s fingerprints in alien skies

If life ever takes hold on a planet, it will have to interact with the air above it, and that interaction can leave chemical fingerprints. On Earth, biology has dramatically reshaped the atmosphere, filling it with oxygen and trace gases that would not persist without constant replenishment. Astronomers are now trying to identify similar “biosignatures” in exoplanet atmospheres, combinations of gases that are hard to explain through geology or photochemistry alone and that might hint at living processes at work.

Researchers working on atmospheric retrieval techniques describe how they search for patterns such as oxygen paired with methane, or unusual levels of nitrous oxide, while also warning that each potential biosignature must be checked against non-biological explanations. That caution is especially important for planets outside the classic habitable zone, where exotic chemistry and intense radiation can mimic some of the same signals that life would produce, making context and detailed modeling as important as the raw detection of a gas.

Beyond the comfort zone: why “unfriendly” orbits are now prime targets

For a long time, planets that orbited too close to their stars or far beyond the habitable zone were treated as curiosities rather than serious candidates in the search for life. That attitude is changing as climate models show that thick atmospheres, strong greenhouse effects, or internal heat can keep surfaces temperate even when starlight alone would not. Some recent work argues that exoplanets well outside the traditional zone may still maintain liquid water under high-pressure atmospheres or beneath icy shells, turning them into compelling testbeds for life’s resilience.

Analyses of these “beyond the habitable zone” worlds explain how astronomers are using transit spectroscopy and thermal phase curves to probe their atmospheres, looking for signs of stability, circulation, and potential surface reservoirs of water. One detailed overview of this shift highlights how planets that were once dismissed as too hot or too cold are now being reconsidered as key pieces of the puzzle, especially when their atmospheres show hints of complex chemistry that cannot be explained by simple, bare-rock models, a point underscored in work on exoplanet atmospheres beyond the habitable zone.

How telescopes peel apart exoplanet atmospheres

Turning a faint dip in starlight into a chemical inventory of a distant world is a technical feat. When a planet passes in front of its star, a tiny fraction of the starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere, imprinting absorption features that reveal the presence of molecules such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, or hydrogen. By repeating these observations over many transits and comparing them across wavelengths, astronomers can reconstruct temperature profiles and cloud layers, even for planets that are hundreds of light-years away.

Reports on current observing campaigns describe how space telescopes and large ground-based instruments are being tuned to capture these subtle signals, often pushing their detectors to the limit. Coverage of this work in mainstream news outlets has emphasized that the same techniques used to characterize hot Jupiters and warm Neptunes are now being applied to smaller, cooler planets, including those that sit just inside or outside the habitable zone, as highlighted in a recent news analysis of atmospheric studies.

JWST’s early hints of atmospheres on small, temperate worlds

The James Webb Space Telescope has quickly become the flagship tool for probing exoplanet atmospheres, and its early results are already reshaping expectations. By capturing high-precision spectra during transits and eclipses, JWST can detect faint atmospheric features on planets that are only slightly larger than Earth and that orbit within or near their stars’ temperate zones. In at least one case, observers have reported tentative evidence of an atmosphere on a rocky planet that receives a level of starlight compatible with surface liquid water.

Detailed coverage of these observations explains how JWST’s infrared instruments picked up subtle spectral signatures that could indicate a compact, possibly water-rich atmosphere, although the data are still being debated and alternative explanations remain on the table. The same reporting stresses that even a “hint” of an atmosphere on a small, potentially habitable exoplanet is a major milestone, because it proves that JWST can reach the sensitivity needed to test climate models directly, a capability showcased in early results on a potentially habitable exoplanet.

Red dwarfs, tidal locking, and the challenge of survival

Many of the most accessible Earth-sized exoplanets orbit red dwarf stars, which are smaller and cooler than the Sun but far more active in their youth. Planets in the nominal habitable zone of these stars tend to be tidally locked, with one hemisphere in permanent daylight and the other in endless night. That configuration raises hard questions about whether an atmosphere can survive intense stellar flares and whether heat can be transported efficiently enough to avoid atmospheric collapse on the dark side.

Astrobiology briefings from space agencies describe how climate models of tidally locked planets show that a sufficiently thick atmosphere, possibly aided by oceans, can redistribute heat and maintain moderate temperatures across large regions of the surface. These studies also note that magnetic fields, atmospheric composition, and cloud feedbacks all play a role in shielding such planets from high-energy radiation, and they frame red dwarf systems as both risky and promising targets in the broader search for life on exoplanets.

Public fascination and scientific caution around “Earth 2.0” headlines

Every time a new exoplanet is announced as “Earth-like,” public excitement surges, often faster than the data can support. Social media posts and comment threads fill with speculation about oceans, continents, and alien civilizations, even when astronomers have measured only a radius, a mass, and a rough orbital distance. That enthusiasm reflects a genuine hunger to understand our place in the universe, but it can also obscure the fact that without atmospheric measurements, claims about habitability are little more than educated guesses.

Recent outreach pieces have tried to bridge that gap by explaining why atmospheric characterization is the crucial next step after detection, and by highlighting how difficult it is to confirm that a planet is truly “Earth-like” in climate rather than just in size. One widely shared explainer on social media stressed that exoplanet atmospheres may reveal whether life could actually survive there and not just whether the orbit looks promising, a point that resonated in a popular discussion of atmospheric clues.

How astronomers prioritize targets in a crowded exoplanet catalog

With thousands of confirmed exoplanets and many more candidates, astronomers cannot study every atmosphere in detail, so they have to choose. Priority often goes to planets that transit bright, nearby stars, where the signal is strongest, and to systems where multiple planets offer a comparative laboratory. Within that subset, researchers weigh factors such as planet size, estimated temperature, and orbital period to decide which worlds are most likely to yield meaningful constraints on climate and potential habitability.

Public-facing explainers on exoplanet surveys describe how this triage process works in practice, noting that some planets are selected because they test the edges of the habitable zone concept, while others are chosen as benchmarks for atmospheric models. One widely circulated post on social media walked through how astronomers start by identifying planets in or near the habitable zone, then refine the list based on stellar type and observational feasibility, illustrating the process with examples of systems where astronomers search for exoplanets that could host alien life.

Community debates: skepticism, hype, and hard questions

Within the scientific community and among engaged amateurs, there is an active debate about how far current data can really take us. Some researchers and enthusiasts argue that talk of biosignatures is premature when most spectra are low resolution and dominated by noise, while others counter that setting up a careful framework for interpreting possible life signals now will prevent overreactions later. These discussions often play out in public forums where new preprints and telescope results are dissected in real time.

One widely discussed thread in an online space community, for example, focused on whether atmospheric studies of planets beyond the habitable zone are a distraction from more promising targets or a necessary step in building a complete theory of planetary climates. Contributors weighed the trade-offs between depth and breadth, with some calling for more focus on a few nearby systems and others pushing for a broader survey of extreme worlds, a debate captured in a community discussion of exoplanet atmospheres.

What extreme atmospheres can teach us about Earth

Studying atmospheres on planets that are nothing like Earth is not just an exercise in curiosity; it also feeds back into our understanding of our own climate. By observing how different mixtures of gases respond to varying levels of starlight, gravity, and rotation, scientists can test the limits of climate models that are also used to project future conditions on Earth. Exotic exoplanets with runaway greenhouse effects or deep, hazy envelopes provide natural experiments that would be impossible to reproduce in a laboratory.

Analytical pieces on this connection point out that insights from exoplanet research have already helped refine models of cloud formation, atmospheric escape, and radiative transfer, all of which matter for long-term climate forecasts here at home. One commentary aimed at a general audience emphasized that understanding how atmospheres evolve under extreme conditions can inform debates about planetary stability and habitability, a theme explored in a broader look at exoplanet science.

The role of video explainers and public education

As the technical details of exoplanet atmospheric science grow more complex, video explainers have become an important bridge between research teams and the wider public. Short documentaries and lecture-style presentations walk viewers through how transit spectroscopy works, why certain molecules are considered potential biosignatures, and what limitations current telescopes face. These formats allow scientists to show real spectra, animations of planetary orbits, and side-by-side comparisons of different atmospheric scenarios.

Several recent videos have focused specifically on the idea that atmospheres beyond the habitable zone can still hold vital clues about life’s possibilities, using graphics to illustrate how thick envelopes of gas or subsurface oceans might sustain habitable niches. One such explainer delved into the physics of light filtering through alien skies and how instruments separate planetary signals from stellar noise, providing a clear overview of how astronomers study exoplanet atmospheres for viewers who may never read a technical paper.

Space agency roadmaps and the next generation of missions

Looking ahead, space agencies are building roadmaps that put atmospheric characterization at the center of exoplanet exploration. Proposed missions include large, space-based observatories with coronagraphs or starshades that can directly image Earth-sized planets and take spectra of their reflected light, as well as specialized transit surveyors that will identify the best targets for follow-up. These plans reflect a consensus that the key to assessing habitability lies in measuring gases, temperatures, and clouds, not just counting planets.

Public briefings and educational materials from these agencies outline how future telescopes will complement existing facilities, with some optimized for the infrared signatures of molecules like water and carbon dioxide, and others tuned to visible wavelengths where oxygen and ozone leave their marks. One widely shared video presentation, for example, walked through the scientific goals of upcoming missions and explained how they will build on current discoveries to search for signs of life on distant worlds, underscoring that atmospheres will be the primary arena where those signs are sought.

Why patience and precision will define the next decade

The emerging focus on exoplanet atmospheres beyond the traditional habitable zone is not a shortcut to quick answers about life in the universe. It is a commitment to a slower, more methodical approach that values detailed characterization over headline-friendly labels. Each spectrum collected, each model refined, and each extreme world mapped in three dimensions adds a piece to a larger mosaic that will eventually tell us how common habitable environments really are, and how often they might host biology.

As telescopes like JWST continue to gather data and as new missions come online, the field will have to balance excitement with skepticism, and bold hypotheses with rigorous tests. The payoff, if it comes, will not be a single dramatic announcement but a gradual accumulation of evidence that some distant atmospheres bear the unmistakable imprint of life, a possibility that is already shaping how scientists talk about future searches for biosignatures and how the public imagines our place among the planets.

More from MorningOverview