Supabase’s rise to a multibillion dollar valuation has less to do with chasing every dollar on the table and more to do with a disciplined refusal to bend its product for short term revenue. By turning down lucrative custom deals, including offers in the seven figure range, the company has tried to protect a product-led strategy that targets thousands of developers instead of a handful of big clients.

That choice, which can sound reckless in the abstract, has become central to how Supabase explains its growth from open source side project to a business investors now value at around 5 billion dollars. I see a pattern that runs through its funding history, its open source posture, and its internal culture: the company keeps trading immediate cash for long term leverage, and the decision to walk away from 1 million dollar contracts is one of the clearest expressions of that philosophy.

How Supabase got to a $5 billion valuation

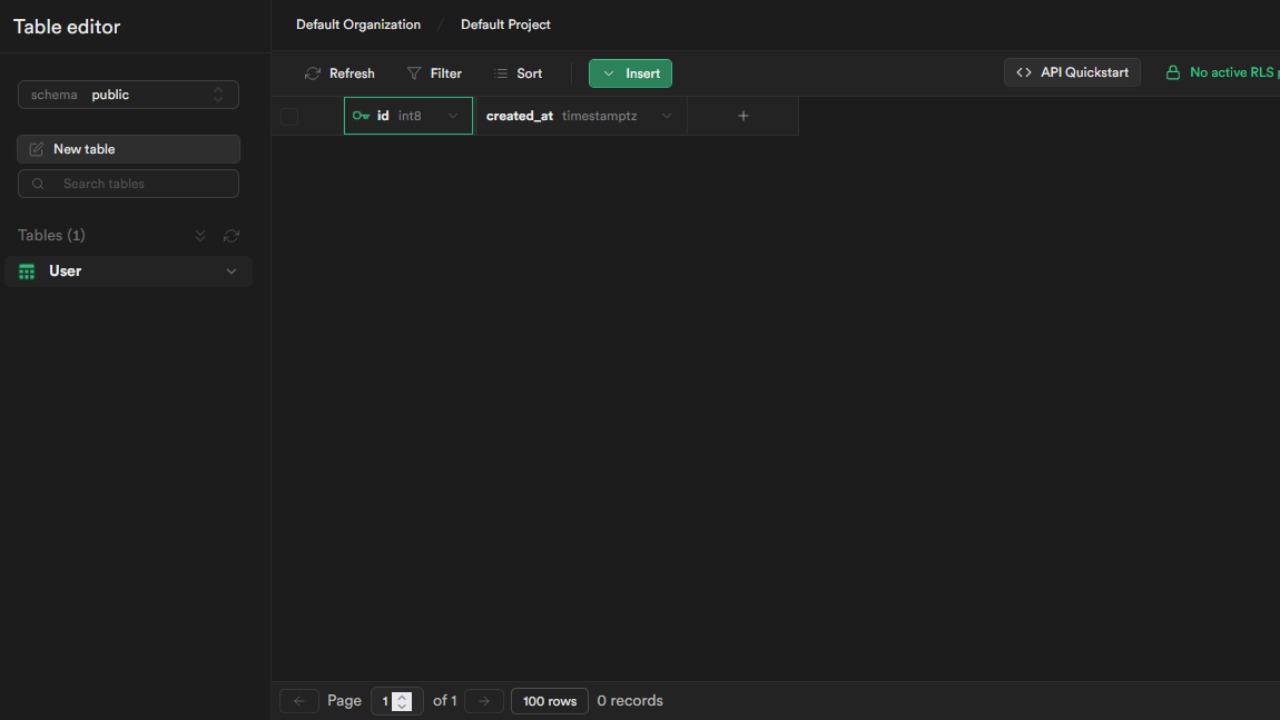

Supabase’s current valuation is the product of a relatively compressed funding journey, but the trajectory is rooted in a simple idea: make it radically easier for developers to build on PostgreSQL without giving up control of their data. The company started by positioning itself as an open source alternative to Firebase, wrapping a managed PostgreSQL database with authentication, storage, and real time APIs so that small teams could ship production apps without hiring a full backend team. Over a few funding rounds, that focus on developer experience and open tooling attracted both a large community and institutional investors who were looking for infrastructure companies that could scale usage quickly.

As the user base grew from early adopters to larger teams, Supabase raised progressively larger rounds at higher valuations, culminating in investors pricing the company at roughly 5 billion dollars in its Series C. That step up reflected not only revenue growth but also the perceived strategic value of a platform that sits directly on top of PostgreSQL, a database that is already entrenched across enterprises. By the time of that round, Supabase had moved from a niche “Firebase for Postgres” pitch to a broader story about being the default data platform for modern applications, which helped justify the multibillion dollar figure.

Why Supabase turns down $1 million custom deals

The most striking detail in Supabase’s growth story is its willingness to reject large, bespoke contracts that could have boosted short term revenue. The company has described walking away from offers in the 1 million dollar range when those deals would have required building one off features, custom integrations, or support commitments that did not align with its core roadmap. From a traditional enterprise sales perspective, that looks counterintuitive, especially for a company that is still scaling and could use the cash to extend runway or hire faster.

Supabase’s leadership has framed those refusals as a deliberate guardrail rather than a moral stance. The logic is that accepting a 1 million dollar custom engagement can quietly turn a product company into a services shop, because engineers start prioritizing the needs of a single large customer over the broader developer base. By saying no to those offers, Supabase has tried to keep its engineering resources focused on features that benefit thousands of users at once, a choice it argues has been essential to reaching a 5 billion dollar valuation instead of becoming a profitable but narrow consultancy.

The product-led growth logic behind saying no

Turning down big checks only makes sense if the underlying growth engine can reliably produce more value over time than those deals would have delivered. Supabase has leaned heavily on a product-led growth model, where developers can sign up, deploy a database, and start building without talking to sales. In that model, the product itself is the primary acquisition and expansion channel, and the company’s job is to remove friction from onboarding, documentation, and scaling so that usage grows organically as customers’ apps succeed.

Custom 1 million dollar deals tend to pull a company away from that dynamic, because they introduce features and workflows that are optimized for a single large client rather than the average user. Supabase has argued that this kind of “feature drift” can slow down the core roadmap, complicate the product, and ultimately reduce the appeal for the broader developer community that drives its recurring revenue. By refusing those distractions, the company has tried to keep its product simple enough for solo developers while still powerful enough for teams, which in turn supports a self serve funnel that can scale to tens of thousands of projects without a proportional increase in headcount.

Protecting the roadmap from enterprise creep

One of the quiet risks for any infrastructure startup is what many founders call “enterprise creep,” the slow shift from building a general purpose platform to maintaining a patchwork of custom features for a handful of large accounts. Supabase’s decision to walk away from 1 million dollar offers is best understood as a defense against that drift. Each bespoke feature request from a big customer can seem harmless in isolation, but over time those exceptions accumulate into a fragmented codebase that is harder to maintain and slower to evolve.

By setting a high bar for what makes it onto the roadmap, Supabase has tried to ensure that new capabilities are driven by patterns it sees across the entire user base rather than the demands of a single logo. The company has emphasized that its roadmap is shaped by open source feedback, community issues, and usage data from its managed platform, not by private contracts. That stance is reflected in how it ships major features, such as improvements to its PostgreSQL tooling and real time APIs, which are released broadly instead of being locked behind enterprise only tiers. The refusal to bend the roadmap for 1 million dollar deals is part of that same philosophy.

Open source as leverage, not a side project

Supabase’s open source posture is not a marketing afterthought, it is a structural advantage that helps explain why it can afford to say no to certain kinds of revenue. By building its core components in public and aligning closely with PostgreSQL, the company taps into a global pool of contributors and early adopters who help test, refine, and extend the platform. That community energy reduces the need to fund every improvement with direct revenue from enterprise contracts, because some of the innovation happens organically in the open.

The company’s funding history shows that investors are not just betting on a hosted database service, they are backing an ecosystem that sits on top of a widely trusted open source database. Supabase can point to GitHub stars, community projects, and third party integrations as evidence that its platform has momentum beyond its own sales pipeline. That makes it easier to justify turning down 1 million dollar custom deals that would have diverted engineering time away from the shared codebase, because the long term value of a healthy open source ecosystem is larger than the short term revenue from a single client.

Aligning pricing with developer scale, not procurement cycles

Supabase’s pricing strategy also helps explain why it prioritizes broad adoption over a few oversized contracts. The company has structured its plans so that developers can start for free or at low cost, then scale up as their applications grow in traffic and complexity. Revenue expands as customers consume more database resources, storage, and bandwidth, which means the company’s financial upside is tied directly to the success of the apps built on its platform rather than to one time implementation fees.

That model is fundamentally at odds with the kind of 1 million dollar custom deals it has declined. Large bespoke contracts often involve lengthy procurement cycles, custom security reviews, and negotiated feature commitments that can lock a vendor into supporting specific workflows for years. Supabase has instead focused on making its managed PostgreSQL offering compelling enough that teams choose it on technical merit and cost transparency, then grow their spend as they trust it with more workloads. The Series C valuation reflects investor confidence that this usage based revenue will compound over time without the company needing to chase every big ticket RFP.

How saying no shapes company culture

Refusing 1 million dollar deals is not just a strategic choice, it is a cultural signal inside Supabase. When leadership consistently turns down revenue that would require bending the roadmap, it tells engineers, product managers, and support teams that the company values long term product integrity over short term financial wins. That clarity can be a powerful recruiting tool for developers who want to work on widely used infrastructure rather than on one off custom projects for a single client.

Internally, this stance also reduces the tension between sales and product that often plagues growing startups. If the default rule is that the roadmap serves the broad user base and not individual contracts, then sales teams are less likely to promise bespoke features to close a deal. Supabase’s ability to raise capital at a 5 billion dollar valuation gives it the financial breathing room to uphold that standard, because it is not under pressure to hit specific enterprise revenue targets at any cost. The culture that emerges from those choices is one where teams are encouraged to think in terms of platform scale rather than quarterly quotas.

Investor expectations and the cost of discipline

None of this discipline would matter if investors were demanding immediate enterprise revenue at the expense of product focus. Supabase’s backers have instead signaled that they are comfortable with a strategy that prioritizes long term platform value, even if that means walking away from 1 million dollar deals in the short run. The Series C round at a 5 billion dollar valuation suggests that investors believe the company can capture a significant share of the market for managed PostgreSQL and developer data platforms without relying on heavy custom services.

That does not mean the discipline is free. By refusing large bespoke contracts, Supabase is effectively betting that its self serve and standard enterprise offerings will generate more than enough revenue to justify its valuation. If growth were to slow, the temptation to accept custom deals would increase, and the company would face renewed pressure to compromise its roadmap. For now, though, the alignment between investor expectations, open source momentum, and product led growth gives Supabase room to keep saying no when a 1 million dollar offer would pull it away from its core mission.

What Supabase’s stance signals to the rest of the market

Supabase’s willingness to reject seven figure custom deals sends a broader message to other infrastructure startups that are trying to balance growth with focus. It shows that it is possible to reach a multibillion dollar valuation by doubling down on a clear product thesis, even when that means leaving money on the table. The company’s experience suggests that investors will reward a coherent strategy that scales across thousands of customers more than a patchwork of bespoke contracts, especially in markets where open source and developer communities can amplify adoption.

For founders and product leaders, the lesson is not that every 1 million dollar deal should be refused, but that each one carries a hidden cost in roadmap complexity and cultural drift. Supabase’s path to a 5 billion dollar valuation illustrates how saying no can be a form of strategic investment, preserving the clarity and simplicity that make a platform attractive in the first place. By treating its product, community, and roadmap as non negotiable assets, the company has turned discipline into a competitive advantage, even when that discipline means walking away from eye catching short term revenue.

More from MorningOverview