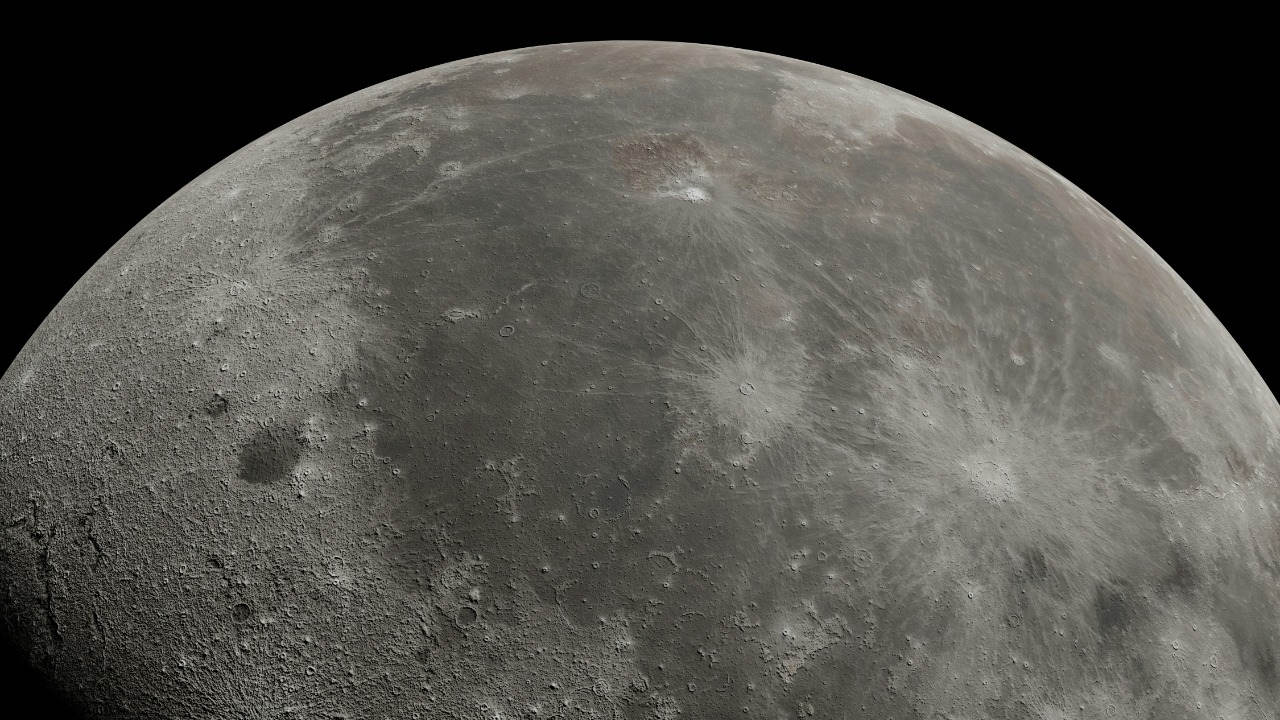

The far side of the Moon has turned out to be far stranger than many planetary scientists expected, and the latest surprise is hiding in the dust under a Chinese rover’s wheels. Instead of behaving like the loose, powdery regolith familiar from Apollo footage, the soil there clumps, cakes and clings in ways that point to a different geological history and new engineering challenges for future missions. That unexpected stickiness is now being traced to subtle differences in grain structure and space weathering, giving researchers a fresh window into how the Moon evolved on opposite hemispheres.

As I follow the emerging data from China’s Chang’e program and the Yutu‑2 rover, I see a story that is less about a quirky surface detail and more about how a single rover track can rewrite assumptions baked into decades of lunar planning. The far side’s adhesive dust is forcing mission designers to rethink everything from wheel design to sample handling, while also sharpening questions about why the Moon’s hidden hemisphere has been shaped so differently from the one that faces Earth.

Yutu‑2’s messy wheels and the first hints of a mystery

The puzzle of clingy lunar soil began as a practical headache for engineers watching Yutu‑2 trundle across Von Kármán crater. Instead of leaving clean tracks in a dry, granular surface, the rover’s wheels picked up dark material that stuck to the treads and sidewalls, forming clumps that sometimes rode along for several wheel rotations before dropping off. That behavior contrasted sharply with the near‑side missions, where Apollo astronauts and earlier Chinese landers saw dust that behaved more like talc than wet sand, and it immediately suggested that the far side’s regolith was not just a mirror copy of the familiar terrain.

Follow‑up analysis of wheel images and traction data showed that the rover was interacting with a surface that compacted more readily and adhered more strongly than expected, especially when the wheels dug into slightly disturbed patches. Reports on the rover’s traverse describe how this “sticky” behavior persisted across multiple stops, indicating that it was a property of the local soil rather than a one‑off patch of unusual material, and early coverage of the mission highlighted how Yutu‑2 had revealed that the Moon’s hidden hemisphere has unusually cohesive soil compared with the near side.

From odd observation to lab-backed explanation

Turning a visual oddity into a physical explanation required more than rover photos, so Chinese scientists turned to a mix of in situ measurements, remote sensing and laboratory simulations. Teams working with Chang’e mission data reconstructed the grain size distribution and mineral makeup of the regolith around the landing site, then compared those results with samples and measurements from near‑side missions. They found that the far‑side soil contains a higher fraction of fine particles and glassy fragments, which increase the number of contact points between grains and make it easier for them to lock together and cling to metal surfaces.

Researchers then used vacuum chambers and simulated lunar dust to reproduce the wheel–soil interactions seen in Yutu‑2 imagery, adjusting grain shapes, impact histories and temperature cycles until the lab behavior matched the rover’s experience. Their work, described in detail by Chinese research institutions, argues that repeated micrometeorite bombardment and local impact melt have created a regolith that is both more fractured and more glass‑rich than typical near‑side soil, which in turn explains why the far‑side surface appears more adhesive and mechanically cohesive. A recent summary of this work notes that Chinese scientists have now linked the stickiness to grain-scale structure shaped by the far side’s unique impact history.

Why the far side’s dust behaves differently from the near side

The Moon’s two hemispheres have long been known to differ in broad strokes, with the near side dominated by dark basaltic maria and the far side covered in brighter, thicker highland crust. The new findings on soil adhesion add a finer‑grained layer to that asymmetry. Because the far side has fewer large lava plains and a thicker crust, it has experienced a different balance of volcanic resurfacing and impact gardening, leaving a surface where ancient highland rocks have been shattered and reworked over longer timescales without being buried under fresh flows of basalt.

That history appears to have produced a regolith that is not only compositionally distinct but also mechanically unusual, with more angular fragments and impact glass that can interlock and cling more readily than the smoother, more weathered grains common in near‑side maria. Chinese teams studying the Yutu‑2 data argue that this helps explain why the soil in Von Kármán crater grips rover wheels more tightly and forms clods instead of simply cascading away, and they frame the result as a key piece of evidence that the far side’s surface has evolved along a separate track from the hemisphere that faces Earth. Coverage of their work emphasizes that they have tied the adhesive behavior to far-side-specific geology rather than a generic lunar property.

Inside the Chinese study that “solved” the stickiness problem

To move from qualitative impressions to a claimed solution, the research teams behind the Yutu‑2 analysis combined multiple strands of evidence into a single model. They started with high‑resolution images of the rover’s wheels and tracks, then folded in ground‑penetrating radar data, thermal measurements and spectral readings of the regolith. By comparing those observations with numerical models of grain–grain and grain–metal interactions under lunar gravity and vacuum, they were able to quantify how much cohesion and adhesion the soil must have to match the rover’s performance, including its traction, sinkage and the way disturbed material clumped.

The resulting explanation points to a combination of ultra‑fine particles, irregular grain shapes and electrostatic charging as the main drivers of the observed stickiness, with impact‑generated glass and breccia playing a central role in setting those properties. Researchers involved in the work have presented it as a comprehensive answer to why the far‑side soil appears more adhesive than its near‑side counterpart, and international coverage has echoed that framing, noting that Chinese scientists say they have solved why the far-side soil is stickier by tying it to specific microphysical characteristics of the regolith.

How state media amplified the discovery at home and abroad

Once the technical papers were in place, Chinese broadcasters and news services moved quickly to turn the findings into a broader narrative about scientific progress and space leadership. Video segments highlighted Yutu‑2’s slow crawl across the crater floor, zooming in on the dirt caked on its wheels as a visual hook before cutting to animations of microscopic grains and impact events. The tone in these pieces framed the sticky soil as both a scientific curiosity and a symbol of how far China’s lunar program has come, with presenters emphasizing that the far side had never been explored on the surface before Chang’e‑4 and Yutu‑2.

Clips shared on social platforms walked viewers through the basic idea that the far side’s dust clings more strongly because its grains are shaped and charged differently, often pairing simple language with dramatic imagery of the cratered landscape. One widely circulated segment described how Chinese scientists had “unfolded” the mystery of the adhesive regolith, using the rover’s wheel tracks as a storytelling device to connect everyday experience with high‑end planetary science, and that coverage has been promoted through state-backed video explainers aimed at both domestic and international audiences.

Global reaction: from social feeds to specialist outlets

The story did not stay within Chinese media for long. International news agencies picked up the findings and repackaged them for readers who have followed the Chang’e missions as part of a broader race to the Moon. Their reports stressed that the far side’s soil is measurably more adhesive than the near side’s, and that this difference has practical implications for future landers and rovers that might operate in the same region. In doing so, they helped shift the narrative from a niche technical detail to a widely discussed example of how new missions can still overturn long‑held assumptions about the lunar surface.

On social platforms, the same agencies used shorter posts and images of Yutu‑2’s dusty wheels to drive engagement, often summarizing the core claim in a single sentence and linking back to more detailed coverage. One such post highlighted that Chinese scientists say they have now explained why soil from the Moon’s far side is stickier than material from the near side, packaging the result as a concise update on lunar science for followers who might never read the underlying papers, and that framing has been shared through brief social media summaries that emphasize the contrast between the two hemispheres.

What sticky regolith means for future lunar hardware

For engineers planning the next wave of lunar missions, the far side’s clingy dust is more than a curiosity, it is a design constraint. Wheels that work well in loose, free‑flowing regolith may bog down or accumulate problematic clumps in more cohesive soil, and mechanisms meant to stay clean, such as solar panel hinges or instrument covers, could be at greater risk of contamination if dust adheres more readily. The Yutu‑2 experience suggests that even relatively slow, light rovers can end up carrying significant amounts of soil on their moving parts, which in turn can affect traction, power generation and thermal control.

That reality is already feeding into discussions about how to harden future landers and rovers against the worst effects of lunar dust, from more aggressive dust‑shedding wheel designs to coatings and electrostatic systems that discourage adhesion. Chinese coverage of the sticky soil findings has explicitly linked the new understanding of regolith behavior to the need for better mission planning, noting that deciphering the far side’s surface properties will help protect hardware and extend mission lifetimes, a point that has been underscored in broadcast segments about future lunar exploration.

Yutu‑2’s broader science haul and the far side’s unique environment

The sticky soil story sits within a larger body of science that Yutu‑2 has delivered from its perch inside the South Pole‑Aitken basin, one of the largest and oldest impact structures in the solar system. By combining its panoramic cameras, spectrometers and radar instruments, the rover has mapped subsurface layers, identified rock types and traced the history of impacts and volcanic activity in the region. Those results have already challenged some expectations about how deeply the basin excavation penetrated the lunar mantle and how later impacts and lava flows reshaped the terrain.

In that context, the discovery that the regolith itself behaves differently from near‑side soil is another reminder that the far side is not just a rotated copy of the hemisphere we see from Earth, but a distinct environment with its own geological and mechanical quirks. Early reports on Yutu‑2’s findings stressed that the rover had encountered soil that was more cohesive and adhesive than expected, and that this behavior was part of a broader pattern of surprises on the far side, a theme that has been explored in depth by outlets covering how the Chinese rover found unusually sticky soil while also probing the basin’s deeper structure.

How scientists and communicators turned wheel tracks into a public moment

One striking aspect of the sticky soil story is how visual it is. Instead of abstract graphs or spectra, the core evidence can be conveyed in a single image of a rover wheel caked in dark dust, or a short clip of the vehicle rolling away with clumps of regolith still attached. Science communicators have leaned into that, using animations and short videos to show how individual grains cling to metal surfaces and how repeated wheel passes can compact the soil into firmer ruts than expected, making the physics of adhesion tangible for non‑specialists.

Short‑form videos in particular have distilled the narrative into a few seconds of footage and a single explanatory line, often pairing Yutu‑2 imagery with simple graphics of dust grains and electric charges. These clips, shared on mainstream and niche platforms alike, have helped turn a technical discussion about regolith mechanics into a widely viewed moment in space science, and one such piece uses rover footage to illustrate how the far-side soil clings to Yutu‑2’s wheels in a way that immediately conveys the oddity of the surface.

Why this matters for the next era of lunar exploration

As more countries and companies target the Moon for science, resources and potential long‑term presence, the details of how its surface behaves will matter more than ever. The far side is especially attractive for radio astronomy and for missions that want to sample ancient crust, but the Yutu‑2 findings suggest that operating there will not be as simple as copying near‑side playbooks. Stickier, more cohesive soil could affect everything from landing plume behavior to how easily astronauts or robots can dig trenches, deploy instruments or build infrastructure using in situ materials.

Specialist coverage of the Yutu‑2 mission has already framed the sticky soil as a cautionary tale and an opportunity, arguing that understanding these differences now will help avoid costly surprises later. Detailed reports on the rover’s traverse note that the far side’s regolith is not only mechanically distinct but also a rich archive of the Moon’s early history, and they highlight how the discovery of adhesive far-side soil is pushing scientists to refine models of lunar evolution while engineers rethink how to design hardware for the next generation of missions.

Open questions and the path ahead

For all the progress made in explaining why the far side’s soil clings so stubbornly, many questions remain open. Researchers still need more direct samples from the region to validate their models of grain composition and structure, and to test how factors like solar wind exposure and local magnetic anomalies might further influence adhesion and cohesion. Future missions that can return regolith from multiple far‑side locations, not just a single crater, will be crucial for determining whether Yutu‑2’s experience reflects a local quirk or a hemisphere‑wide pattern.

In the meantime, the sticky soil story stands as a reminder that even familiar worlds can surprise us when we look from a new angle or land in a new place. The far side of the Moon, once a blank map edge in lunar atlases, is now revealing itself as a complex, sometimes unruly environment where dust behaves in ways that challenge both our theories and our hardware. As more data arrive and more rovers follow Yutu‑2’s tracks, I expect that the clinging grains under its wheels will keep shaping how scientists think about the Moon and how engineers prepare to work on its most remote frontier.

More from MorningOverview