Light-guided nanorobots are moving bone science from slow healing to on-demand growth, promising a future where fractures and implants recover far faster than they do today. By converting carefully tuned light into mechanical cues at the cellular level, these tiny devices can push bone-forming cells to multiply and mature at a pace that traditional therapies have never matched.

As researchers refine how these nanoscale machines interact with living tissue, they are also rewriting the rulebook on how surgeons, pharmacists, and educators think about regeneration. I see this work not as a niche lab curiosity, but as a catalyst that could reshape orthopedic care, drug delivery, and even how we teach the next generation of clinicians to work at the interface of light, matter, and biology.

How light-controlled nanorobots coax bone cells to grow

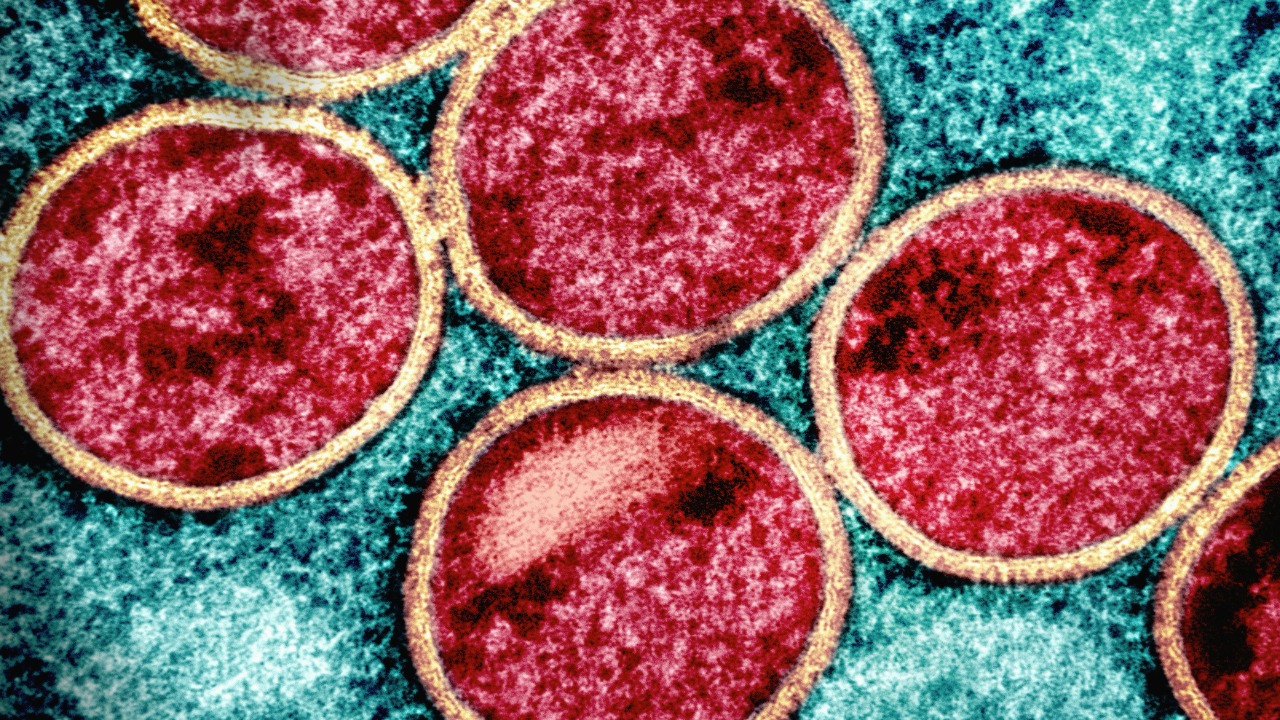

The core breakthrough behind light-tuned nanobots is deceptively simple: use light as a remote control to trigger mechanical stimulation right where bone cells live. In recent experiments, researchers have designed nanoscale structures that respond to specific wavelengths by twisting, vibrating, or shifting, which in turn nudges osteoblasts to proliferate and lay down new matrix much more quickly than under standard culture conditions, as described in reports on light-controlled nanorobots. Instead of flooding the body with systemic drugs, the strategy is to localize both the stimulus and the response, using light as a precise trigger that can be switched on or off in milliseconds.

What makes this approach so powerful is that bone cells are naturally sensitive to mechanical forces, from everyday walking to the microstrains inside a healing fracture. By embedding nanorobots that convert optical energy into tiny pushes and pulls, scientists are essentially amplifying the body’s own language of mechanotransduction. The early data suggest that when these devices are tuned correctly, they can accelerate early-stage bone cell growth without the broad side effects that come with systemic growth factors, a contrast that becomes clear when compared with more traditional regenerative strategies detailed in foundational work on bone tissue engineering.

From passive scaffolds to active nanoscale machines

For decades, bone regeneration research has leaned heavily on passive scaffolds, porous materials that provide a physical framework for cells to cling to while new tissue forms. Those structures, often built from ceramics or biodegradable polymers, have been refined to mimic the stiffness and architecture of native bone, as seen in early analyses of nanotechnology in bone tissue engineering. Yet even the most sophisticated scaffold is essentially a static stage, waiting for cells and growth factors to do the real work.

Light-responsive nanorobots change that equation by turning the scaffold into an active participant in healing. Instead of simply holding cells in place, nanoscale components can be embedded or attached so they respond to external light with controlled motion, effectively transforming a passive matrix into a dynamic training ground for osteoblasts. When I compare this to the earlier generation of nanostructured surfaces that only offered topographical cues, the shift toward programmable, light-driven behavior looks like a step change in how we think about biomaterials, aligning with the broader move from inert implants to smart, responsive systems that earlier nanomedicine reviews only began to anticipate.

Clinical stakes: fractures, implants, and fragile patients

The clinical need for faster, more reliable bone healing is not abstract, it is written into every hip fracture in an older adult and every spinal fusion that struggles to fuse. Traditional strategies rely on immobilization, systemic drugs, and sometimes bone grafts, all of which carry risks and often require long recovery times that can be devastating for patients with limited mobility or complex medical histories. When I look at how precisely controlled mechanical cues from light-activated nanorobots could shorten that window, I see a direct line to fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, and less dependence on systemic therapies that can interfere with other treatments, such as long-term anticoagulation therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease.

There is also a clear opportunity in orthopedic implants, where loosening and poor integration remain stubborn problems, especially in people with osteoporosis or metabolic bone disease. If surgeons could pair a titanium hip or dental implant with a coating of light-responsive nanodevices, then periodically stimulate the interface to encourage bone in-growth, the result could be a more stable, longer-lasting bond between metal and living tissue. That kind of targeted, on-demand stimulation would be a sharp departure from current practice, where clinicians mostly wait and watch, guided by imaging and clinical signs rather than by programmable tools that can directly modulate the healing microenvironment.

Engineering challenges at the intersection of light and biology

Turning a promising lab concept into a clinical tool means confronting the messy realities of light traveling through tissue, immune responses, and long-term safety. Visible and near-infrared light can penetrate only so far into the body, which is why many early demonstrations of light-tuned nanobots focus on surface or shallow tissues, or on in vitro systems where illumination is straightforward. To make this work deep inside a femur or vertebra, engineers will need to balance wavelength, power, and exposure time so that nanorobots receive enough energy to move without overheating or damaging surrounding cells, a tradeoff that echoes the careful calibration seen in other light-based biomedical tools, including educational demonstrations of optical control in nanoscale systems.

Biocompatibility is just as critical, because any foreign material that lingers in bone must avoid triggering chronic inflammation or interfering with remodeling. Many of the materials used in nanorobotics, from gold nanoparticles to silica-based structures, already have a track record in drug delivery and imaging, but long-term, mechanically active implants are a different proposition. I find it telling that earlier work on nanostructured bone scaffolds emphasized surface chemistry and degradation profiles, while the new generation of light-responsive devices must also account for repeated mechanical actuation over months or years, a design space that pushes beyond the static material considerations described in classic bone regeneration frameworks.

Training the next wave of nano-literate clinicians

As light-tuned nanobots move closer to clinical reality, the gap between what the technology can do and what frontline clinicians understand becomes a strategic risk. Orthopedic surgeons, pharmacists, and nurses will need fluency in concepts like wavelength-specific activation, nanoscale force generation, and the interplay between mechanical cues and cell signaling. I see this as part of a broader shift in health professions education, where curricula are already being updated to integrate advanced therapeutics and device literacy, as reflected in contemporary discussions of pharmacy education reform that emphasize emerging technologies and interprofessional training.

Building that literacy will also require rethinking how complex physical and chemical concepts are taught to diverse learners, including students with disabilities who may engage with material differently. Detailed guidance on adapting laboratory and classroom experiences, such as the strategies outlined for teaching chemistry to students with disabilities, offers a template for making nano-focused content accessible without diluting its rigor. If future clinicians are to make informed decisions about when and how to deploy light-responsive nanorobots in bone repair, they will need not only technical knowledge but also inclusive educational environments that prepare a wide range of practitioners to engage with these tools.

Data, documentation, and the ethics of nano-accelerated healing

Rapidly growing bone with light-guided nanobots is not just a technical feat, it is an ethical and regulatory challenge that hinges on how data are collected, interpreted, and communicated. Clinical trials will need to capture not only radiographic evidence of faster healing but also long-term outcomes like implant longevity, pain, and quality of life, all documented with the kind of precision and consistency that major style and reporting standards demand. When I look at the detailed rules for medical writing and citation in resources such as the AMA Manual of Style, it is clear that any claims about accelerated bone growth will have to be backed by rigorously structured evidence if they are to influence guidelines and reimbursement.

Behind that documentation lies a growing ecosystem of digital tools that manage protocols, imaging, and patient-reported outcomes, many of them powered by machine learning models trained on large technical corpora. Datasets that aggregate scientific PDFs, such as collections of educational and research documents, are already feeding systems that can help researchers spot patterns in how different nanomaterials perform in bone. I see a responsibility here to ensure that these tools are used to enhance transparency rather than obscure uncertainty, especially when the interventions in question are as powerful and unfamiliar to patients as nanoscale machines that can be switched on with light.

From lab bench to interactive models and patient conversations

One of the most striking aspects of light-tuned nanorobots is how abstract they can seem to patients who are used to thinking in terms of casts, screws, and physical therapy. Bridging that gap will require not only clear language but also visual and interactive explanations that make nanoscale processes tangible. Educational platforms that let users manipulate virtual particles or build simple simulations, such as projects created with block-based visual programming tools, hint at how clinicians and educators might one day show patients what it means to have tiny devices responding to light inside a healing bone.

For those of us who write about these advances, there is a parallel obligation to describe them in ways that are accurate, accessible, and grounded in evidence. That means respecting both scientific nuance and editorial standards, from how we explain mechanotransduction to how we cite key trials and regulatory decisions. As light-controlled nanorobots move from experimental setups into real-world orthopedic practice, the conversation around them will be shaped as much by careful communication as by the underlying engineering, and I see that communication as part of the same continuum of innovation that began with early nanotechnology applications in bone and now extends into a future where bone healing can be tuned with a beam of light.

More from MorningOverview