Venus spins slowly, yet its upper atmosphere races around the planet in just a few days, driving hurricane‑force winds that have puzzled scientists for decades. Researchers now argue they have isolated the main engine behind this super‑rotation, turning a long‑standing mystery into a testable physical mechanism. Their work is reshaping how I think about Venus, not as an inexplicable outlier, but as a laboratory for understanding how atmospheres behave on worlds across the Solar System and beyond.

By tying the planet’s ferocious winds to specific patterns of solar heating and cloud‑top dynamics, the new research links Venus’s climate to its geology and even to the prospects for future landers. The same processes that whip the atmosphere around the planet also help sculpt its surface, influence its crushing greenhouse conditions, and set the stage for the next generation of missions that will try to survive there.

Why Venus’s atmosphere races while the planet crawls

Any explanation for Venus’s winds has to start with a basic contradiction: the solid planet rotates once every 243 Earth days, yet the atmosphere at the cloud tops circles the globe in roughly four Earth days. That means the air is moving about sixty times faster than the surface, a regime scientists call atmospheric super‑rotation. Spacecraft and telescopic observations have repeatedly confirmed that these winds reach hundreds of kilometers per hour at altitudes near the bright cloud deck, while the dense air closer to the ground moves more sluggishly, creating a vertical stack of very different flow regimes that must somehow be powered and maintained over time, as summarized in widely cited Venus facts.

For years, models have suggested that a combination of solar heating, planetary rotation, and wave activity could sustain this super‑rotation, but no single driver had been pinned down with enough confidence to satisfy both observers and theorists. The new work zeroes in on how uneven heating of the thick cloud layer, combined with the way that energy is transported from the dayside to the nightside, can generate a net torque that keeps the atmosphere spinning far faster than the surface. By focusing on the energy budget of the upper atmosphere rather than only on the deep greenhouse below, the researchers provide a framework that can be checked against cloud‑tracking data and thermal measurements from orbiting spacecraft.

The key driver scientists have finally isolated

The latest analyses argue that the dominant engine behind Venus’s extreme winds is the pattern of thermal tides, global‑scale waves in temperature and pressure that are locked to the cycle of sunlight. These tides arise because the planet’s thick clouds absorb solar energy on the dayside, then reradiate and redistribute that heat as the atmosphere rotates into night, creating a repeating pattern that can push on the air much like ocean tides push on water. By carefully comparing simulated thermal tides with observed wind speeds and cloud motions, researchers have concluded that this mechanism can account for most of the momentum needed to sustain super‑rotation, a result highlighted in new work on the key driver of Venus winds.

What makes this result compelling is that it does not rely on exotic physics or finely tuned assumptions. Instead, it treats Venus as a system where solar heating, radiative cooling, and planetary rotation interact in a predictable way, then shows that the resulting thermal tides naturally pump angular momentum into the upper atmosphere. Independent modeling and observational studies have converged on the same conclusion, reinforcing the idea that these tides are not a minor correction but the primary engine of the global circulation, as echoed in research spotlights that dissect the dominant wind mechanism.

How models and observations finally line up

For decades, one of the biggest frustrations in Venus science was the gap between general circulation models and what spacecraft actually saw at the cloud tops. Simulations could produce super‑rotation, but often with the wrong speed, altitude structure, or sensitivity to solar heating, leaving open the question of whether they were capturing the real physics or just tuning parameters. The new generation of models explicitly resolves thermal tides and their interaction with the background flow, then checks those predictions against long‑baseline cloud‑tracking data and thermal emission measurements, a strategy that has been described in detail in recent coverage of Venus wind modeling.

By matching not only the peak wind speeds but also the vertical profile of the circulation and its day‑night asymmetries, these studies give me more confidence that the community is finally closing the loop between theory and observation. The agreement extends to subtle features, such as how the super‑rotation varies with latitude and how waves propagate from the lower atmosphere into the cloud deck, which are sensitive tests of any proposed driver. When models that include realistic thermal tides reproduce these patterns without ad hoc tweaks, it suggests that scientists are no longer just fitting curves to data, but are instead capturing the underlying engine that keeps Venus’s atmosphere in overdrive.

What the winds reveal about Venus’s mysterious surface

Understanding the atmosphere is not just an abstract fluid‑dynamics problem, because those same winds help shape what little we can infer about Venus’s surface. The planet is cloaked in clouds that are opaque to visible light, so radar and infrared observations have to work through or around the atmosphere to map mountains, plains, and volcanic features. The circulation patterns driven by thermal tides influence how heat is transported downward and how chemical species move between the clouds and the lower atmosphere, which in turn affects how the surface cools, weathers, and possibly resurfaces over geologic time, a connection that underpins new efforts to explain Venus’s mysterious surface.

Recent analyses of radar topography and gravity data suggest that parts of Venus’s crust may be more mobile than previously thought, with blocks that flex and jostle in ways that hint at a unique style of tectonics. The atmosphere, loaded with carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid, interacts with this surface through intense pressure and temperature, and the winds help distribute volcanic gases and aerosols that can leave signatures in radar reflectivity and emissivity. By tying the super‑rotation to specific heating patterns, scientists can better predict where hot spots, cloud breaks, or compositional anomalies might appear, which is crucial for interpreting puzzling surface features that have been highlighted in new work on bizarre Venus terrain.

Lessons from Magellan and the radar era

The most detailed global view of Venus’s surface still comes from NASA’s Magellan mission, which used synthetic aperture radar to map about 98 percent of the planet in the early 1990s. Those images revealed vast volcanic plains, coronae, and tesserae, along with relatively few impact craters, implying a surface that has been geologically active on timescales of hundreds of millions of years. Scientists have spent decades mining the Magellan archive to understand how such a world operates under a crushing atmosphere, and recent reanalyses have focused on how atmospheric conditions, including the super‑rotating winds, might influence radar backscatter and the apparent roughness of different terrains, as described in renewed Magellan surface studies.

These radar data are now being revisited with the benefit of improved atmospheric models that incorporate the newly identified wind driver. When I look at how researchers are combining Magellan’s maps with modern simulations of temperature, pressure, and cloud opacity, it is clear that the atmosphere can no longer be treated as a static curtain in front of the surface. Instead, the super‑rotation and its associated waves modulate how radar signals interact with the ground, which can subtly bias interpretations of elevation, roughness, or even possible volcanic changes over time. By folding the dynamics of the winds into these analyses, scientists hope to extract more reliable clues about whether Venus is still volcanically active and how its crust responds to the intense conditions at the base of the atmosphere.

Why Venus matters for exoplanets and climate physics

Pinning down the main engine of Venus’s winds has implications that reach far beyond one planet. Many exoplanets discovered so far orbit close to their stars and may be tidally locked, with permanent daysides and nightsides that create strong thermal contrasts. In such environments, thermal tides and day‑night heating patterns are expected to play a major role in shaping atmospheric circulation, just as they do on Venus. By testing these ideas on a nearby world where spacecraft can directly measure wind speeds, temperatures, and cloud structures, scientists gain a benchmark for interpreting the phase curves and spectra of distant planets that cannot be resolved in detail, a connection that is often emphasized in expert Venus climate discussions.

There is also a sobering climate lesson. Venus and Earth are similar in size and bulk composition, yet Venus’s surface temperature is hot enough to melt lead, thanks to a runaway greenhouse driven by its thick carbon dioxide atmosphere. Understanding how energy moves through that atmosphere, including how super‑rotation redistributes heat from equator to pole and from day to night, helps refine models of how greenhouse effects can escalate under different boundary conditions. When I see researchers using Venus as a test case for radiative transfer and cloud feedbacks, I am reminded that our own climate system operates under much gentler conditions, but according to the same physical laws that govern the extreme Venusian greenhouse.

The next wave of missions and what they will test

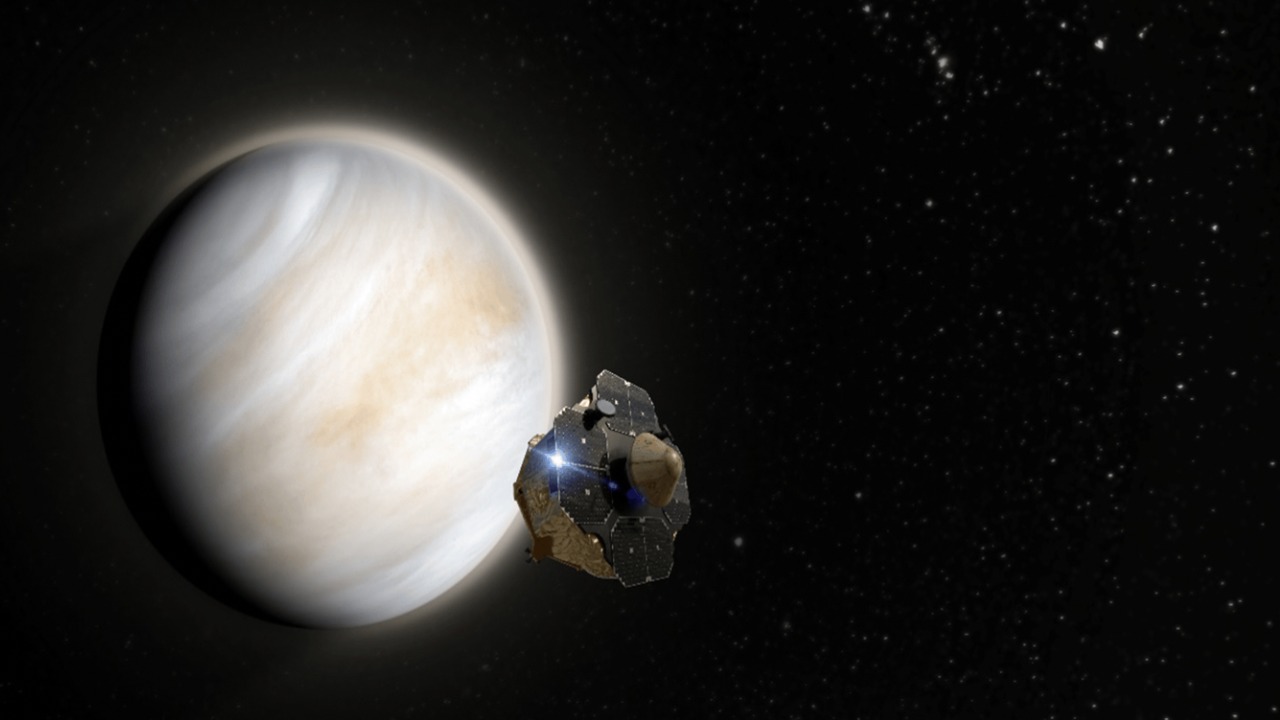

The identification of a primary driver for Venus’s winds arrives just as a new fleet of missions is being planned to revisit the planet. Future orbiters and probes will be able to test the thermal tide hypothesis by measuring temperature, pressure, and wind profiles at multiple altitudes and local times, building on the foundation laid by earlier spacecraft. Mission concepts emphasize high‑resolution mapping of the cloud tops, in situ sampling of the atmosphere, and improved radar imaging of the surface, all of which will benefit from a clearer understanding of how the super‑rotation behaves and how it might vary over time, themes that feature prominently in recent mission briefings.

For engineers designing entry probes and landers, knowing the structure and driver of the winds is not just an academic concern. Descent trajectories, parachute systems, and communication links all depend on accurate predictions of wind shear, turbulence, and temperature gradients. With thermal tides now recognized as the main engine of the upper‑level circulation, mission planners can better anticipate how conditions will change from day to night and from equator to higher latitudes. That, in turn, should improve the odds that the next generation of hardware will survive long enough on the surface to connect the dots between atmospheric dynamics, geological activity, and the long‑term evolution of a world that offers both a warning and a window into planetary climate physics.

More from MorningOverview