Astronomers sometimes talk about the universe as a series of puzzles that arrive one pixel at a time, and few images capture that better than a single, unresolved red speck at the edge of a telescope’s field. A lone crimson point can signal a distant galaxy, a dying star, or something that does not yet fit neatly into any category, and the stakes are high because each new outlier forces a rethink of how the cosmos grows and evolves. When I look at how scientists respond to such anomalies, I see less a tidy eureka moment and more a long, methodical process of testing ideas, arguing over data, and slowly deciding whether that tiny dot really represents a new kind of cosmic beast or simply a familiar object seen in an unfamiliar light.

Why a single red pixel can upend a cosmic story

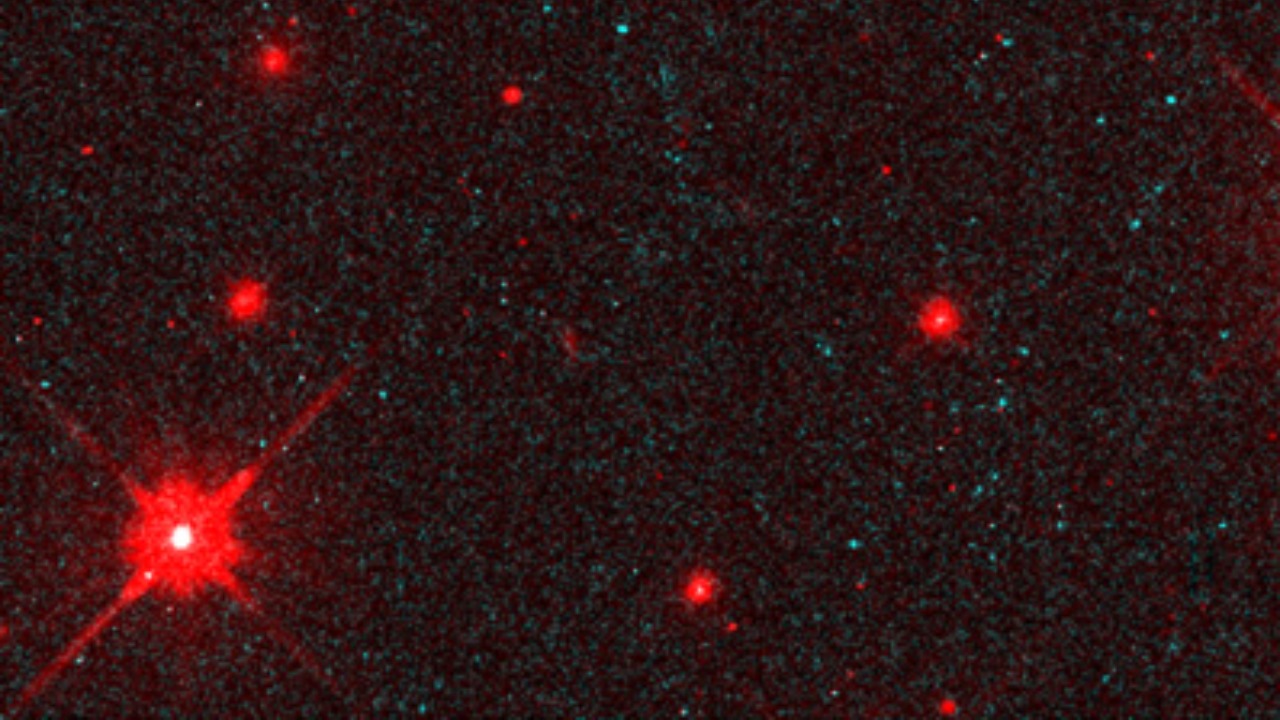

In modern astronomy, a “tiny red dot” is rarely just a pretty feature on a deep-space image; it is usually shorthand for an object whose light has been stretched to longer, redder wavelengths by the expansion of the universe. That stretching, or redshift, turns a faint source into a time capsule, carrying information from an era when galaxies were young and the first heavy elements were still being forged. When a survey image reveals a compact, unusually red point that does not match known patterns, researchers treat it as a potential clue that their models of early galaxy growth or black hole formation might be incomplete, and they begin the slow work of checking whether the signal is real, how it behaves across different filters, and whether it lines up with any cataloged sources.

That process is less glamorous than the headline suggests, and it depends on a culture of open-ended questioning that is familiar to anyone who has watched a large online community pick apart a tricky problem. In the same way that a sprawling workplace discussion thread can surface edge cases and overlooked details, astronomers rely on collaborative scrutiny to decide whether a new candidate object is truly extraordinary or just an artifact of the data. The back-and-forth that plays out in internal mailing lists and conference Slack channels has the same energy as a long-running public conversation about how to interpret ambiguous situations, a dynamic that is easy to recognize in the kind of wide-ranging exchanges archived in an open discussion thread where dozens of people test ideas, share experiences, and refine each other’s assumptions.

From raw pixels to a working hypothesis

Turning that faint red point into a credible scientific claim starts with a chain of decisions that look, from the outside, almost like a carefully managed project plan. Teams must decide which instruments to use, how to calibrate them, and which analysis pipelines to trust, because a misstep at any stage can turn a promising anomaly into a dead end. I think of this as a kind of editorial process for data, where raw images are the first draft and each round of cleaning, cross-checking, and modeling is another revision that either sharpens the story or reveals that the initial excitement was misplaced.

Researchers who specialize in this work often keep meticulous records of their choices, from exposure times to filter combinations, so that others can retrace their steps and challenge the conclusions. That habit mirrors the way a careful writer or technologist maintains a running log of experiments, drafts, and side projects, building an archive that shows not just the polished result but the path taken to reach it. The value of that transparency is clear when you browse a detailed personal project archive that lays out work over time, because it demonstrates how each decision builds on the last and how apparent breakthroughs usually emerge from a long sequence of incremental refinements rather than a single dramatic leap.

Why astronomers obsess over ingredients and recipes

Once the data are in hand, the real argument begins over what physical ingredients could produce the observed light. A tiny red source might be a compact galaxy packed with young stars, a dust-shrouded region where starlight is heavily reddened, or a supermassive black hole whose surrounding disk glows fiercely in the infrared. To sort those possibilities, astronomers compare the object’s colors, brightness, and variability to synthetic “recipes” generated by computer models, adjusting parameters such as star formation rate, metallicity, and dust content until the simulated spectrum lines up with the measurements. The exercise is less about forcing a fit and more about asking which combinations of ingredients are plausible given what is known about the early universe.

That mindset is not far from the way a skilled cook approaches a complex dish, treating each component as part of a larger balance rather than an isolated element. When a chef explains why a particular lasagna works, they talk about the layering of textures, the ratio of sauce to pasta, and the way long, slow cooking transforms simple ingredients into something richer and more coherent. Reading a detailed breakdown of how to assemble the best lasagna ever is a reminder that success often lies in understanding how small adjustments in one layer ripple through the entire structure, which is exactly how astrophysicists think about tweaking dust content or star formation histories to see how those changes reshape the emergent spectrum of a distant galaxy.

Managing the machinery behind a single red dot

Behind every intriguing deep-space speck sits a sprawling infrastructure of telescopes, data centers, and observing schedules that must be coordinated with almost obsessive care. Securing follow-up time on a major observatory requires detailed proposals, clear justifications, and a plan for how the new observations will resolve specific ambiguities in the existing data. Once the observations are approved, teams must choreograph instrument settings, calibration frames, and data transfers so that the resulting measurements are both scientifically useful and compatible with the pipelines that will process them, a task that feels less like solitary stargazing and more like running a complex service business with limited resources and high expectations.

The parallels to real-world operations are hard to miss, especially in fields where margins are tight and every decision about staffing, inventory, or scheduling can make or break the outcome. In that sense, the way an observatory allocates telescope time and manages its queue of targets resembles the structured approach laid out in a practical guide to restaurant management, where success depends on aligning front-of-house demands with back-of-house capacity. Both environments reward clear communication, contingency planning, and a willingness to adjust quickly when conditions change, whether that means a sudden storm closing an observing window or an unexpected rush of customers forcing a shift in the evening’s menu.

How communities stress-test extraordinary claims

Even the most carefully managed observation campaign does not guarantee that a strange red object will hold up under scrutiny, which is why the broader scientific community plays such a crucial role in validating or debunking early interpretations. After an initial preprint circulates, other groups dig into the methods, reanalyze the data, and sometimes pull in independent observations to see whether the claimed redshift or luminosity survives fresh eyes. That process can be messy and contentious, but it is also where the field’s collective judgment emerges, as competing teams argue over calibration choices, selection effects, and the statistical weight of the evidence.

The dynamic is similar to what happens in any large, loosely organized forum where people bring different expertise and perspectives to a shared problem. Long-running feeds that aggregate posts, comments, and updates from multiple sources show how ideas evolve as they are passed around, challenged, and refined, with some threads fading quietly while others spark sustained debate. Browsing a busy RSS aggregation channel gives a sense of how quickly a community can surface patterns, flag inconsistencies, and push back on overconfident claims, which is exactly what happens when astronomers converge on a provocative result and start testing whether it really demands a new category of cosmic object or can be folded into existing frameworks.

Living with uncertainty while the data accumulate

For all the excitement that surrounds a possible new class of object, the reality is that many such candidates spend years in a kind of limbo while better data accumulate. Spectroscopic measurements might be too noisy to pin down a precise redshift, or conflicting photometric catalogs might disagree on the object’s brightness in key filters, leaving room for multiple interpretations. During that period, researchers must balance the urge to publish bold explanations with the responsibility to flag uncertainties clearly, knowing that early narratives can be hard to dislodge even when later evidence points in a different direction.

That tension between curiosity and caution is familiar to anyone who has watched a community wrestle with incomplete information in public, where people share tentative theories, revise their views, and sometimes admit that a cherished explanation no longer fits the facts. The tone of those exchanges often shifts over time, from initial enthusiasm to more measured analysis as new details emerge, a pattern that shows up in reflective workplace conversations about ambiguous situations, such as those captured in an open workplace thread where participants revisit earlier assumptions in light of additional context. In astronomy, that same willingness to update beliefs is what keeps the field from locking prematurely onto a single story about what a puzzling red dot must represent.

Why the smallest anomalies keep reshaping the big picture

Over the long term, the real impact of these tiny, enigmatic sources is not just whether any one of them turns out to be a brand-new kind of object, but how they collectively pressure-test the models that describe the universe at large. Each time a compact, high-redshift candidate challenges expectations about how quickly stars can form or how massive black holes can grow, theorists must decide whether to tweak existing parameters or entertain more radical revisions. That iterative process, in which outliers are alternately absorbed into the prevailing framework or used as leverage to pry it open, is how cosmology gradually moves from broad sketches to more precise, predictive theories.

Following that evolution requires patience and a willingness to sit with unresolved questions, traits that are easier to cultivate in spaces where people are used to returning to the same themes over months or years. In some online communities, recurring open conversations provide a kind of longitudinal record of how collective thinking shifts, as participants revisit familiar topics with fresh experiences and new information. The rhythm of those discussions, visible in a recurring open conversation series, mirrors the way astronomers circle back to puzzling data sets each observing season, armed with better instruments and sharper questions. In both cases, the smallest anomalies can, over time, reshape the entire narrative, turning a single red pixel at the edge of a frame into a catalyst for reimagining what the universe is capable of.

More from MorningOverview