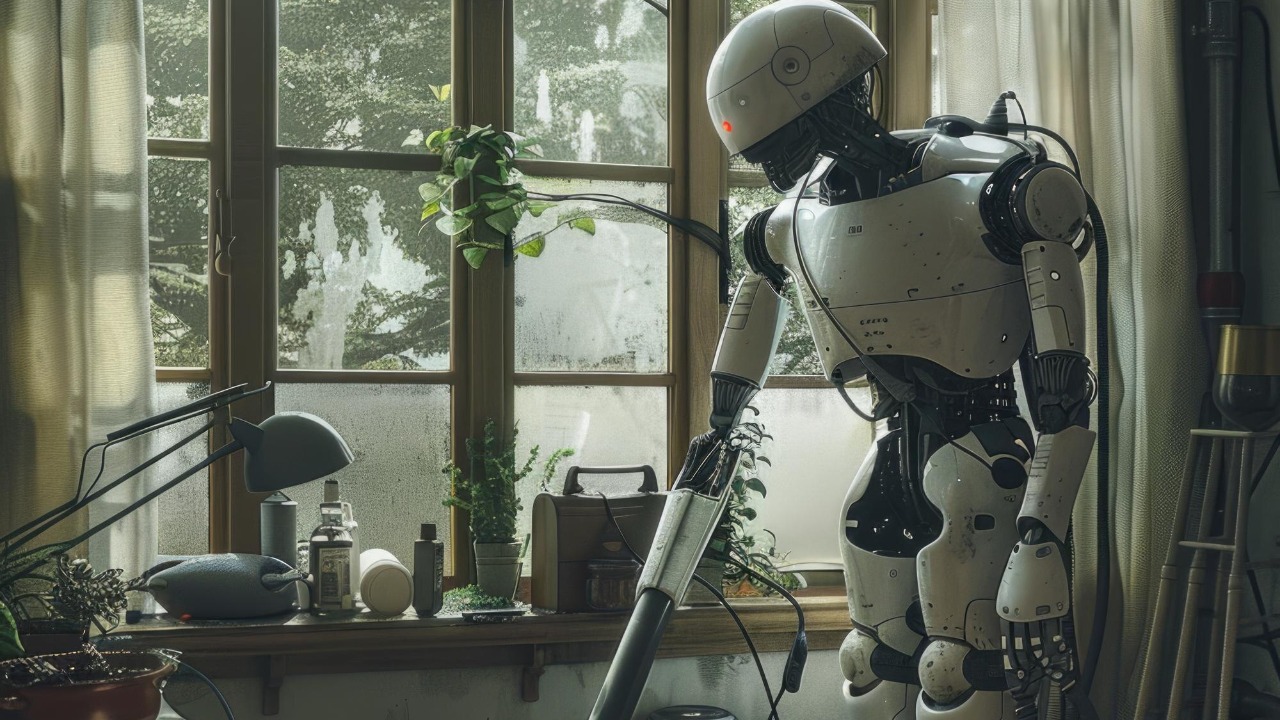

Humanoid robots are edging closer to everyday life, and a new wave of US startups is betting that the real breakthrough will not be in metal and motors but in the “brains” that let machines understand messy human spaces. Instead of building yet another biped from scratch, these companies are training software control systems that can be dropped into any compatible body and then taught to handle household chores, warehouse tasks, or office errands. I see this shift as a move away from sci‑fi spectacle toward something more prosaic but far more disruptive: robots that quietly learn to do the boring work people are desperate to offload.

That ambition is colliding with a hard reality: homes and workplaces are chaotic, language is ambiguous, and human expectations are shaped by years of interacting with smartphones and chatbots that already feel semi-intelligent. The startups trying to wire humanoids for chores are not just solving robotics problems, they are also wrestling with how people communicate instructions, how we manage attention, and how we decide which tasks are worth delegating in the first place. Those human factors, more than any single sensor or actuator, will determine whether robot “brains” ever become as common as dishwashers or Wi‑Fi routers.

The shift from hardware to “robot brains”

For years, humanoid projects were judged on how gracefully a robot could walk or how dramatically it could backflip, but the new generation of US startups is treating the physical platform as a commodity and pouring effort into the software layer that decides what to do next. In this model, the “brain” is a stack of perception, planning, and language tools that can be trained in simulation, refined in the lab, and then deployed into different humanoid bodies without rewriting everything from scratch. I see this as a direct response to the industry’s frustration with bespoke hardware that looks impressive in demos yet struggles to adapt when the environment or the task changes.

That software-first mindset borrows heavily from how developers already iterate on complex systems, from open discussion threads where engineers dissect failure modes to public bug lists that track every misstep. The same culture that fuels candid technical debates on platforms like developer forums is now shaping how roboticists share training tricks, benchmark results, and hard-won lessons about getting machines to cope with cluttered kitchens or narrow staircases. By treating the robot body as just another deployment target, these startups are trying to move humanoids into the same rapid improvement cycle that transformed web apps and mobile software.

Teaching robots to understand human chores

Training a humanoid to fold laundry or unload a dishwasher is not just a matter of memorizing motions, it is about interpreting vague instructions that humans barely think about. When someone says “tidy the living room,” they are compressing a long list of sub-tasks, priorities, and social norms that a robot has to unpack: which objects are out of place, what “tidy” looks like in this household, and which items are off-limits. Startups focused on chore-capable “brains” are leaning on large language models and task planners that can translate natural language into step-by-step action plans, then adjust on the fly when a pet walks through the scene or a human changes their mind mid-command.

In practice, that means drawing on the same conversational patterns people already use with AI assistants, from asking for help with research to delegating repetitive digital work. The way users describe their needs in everyday tools, including how they explain what they use chatbots for, becomes a kind of training data for how robots should interpret chore requests in the physical world. If a person is comfortable saying “sort the mail, pay the electricity bill, and remind me to call the plumber,” they are not far from saying “sort the packages by room, take out the recycling, and flag anything that looks urgent,” then expecting a humanoid to handle the rest.

From to-do lists to embodied task management

One of the most revealing shifts in this space is how chore-capable robots are being framed as physical extensions of the productivity tools people already rely on. Instead of treating a humanoid as a novelty gadget, some startups pitch their “brains” as the next step after digital task managers: the same system that tracks your errands could eventually dispatch a robot to execute them. That vision turns the familiar to-do list into a bridge between abstract planning and embodied action, where each checkbox is something a machine might physically complete on your behalf.

The logic is visible in how people already structure their days with recurring tasks, priority flags, and shared lists that coordinate families or teams. Public task boards that spell out everything from grocery runs to deep-cleaning schedules, like the kind of structured lists seen in online planners, map neatly onto what a robot “brain” needs to know: what to do, in what order, and with what constraints. When those digital plans are paired with a humanoid that can navigate hallways, recognize objects, and manipulate tools, the line between planning software and domestic labor starts to blur.

Why language precision suddenly matters at home

As soon as a robot is expected to act on spoken or written instructions in a real kitchen or office, the fuzziness of everyday language becomes a safety and reliability problem. Humans routinely rely on context, tone, and shared history to interpret phrases like “put that over there” or “clean this up,” but a robot “brain” has to map each word to a specific object, location, and action. That is pushing startups to care about the fine-grained meaning of phrases and the subtle differences between near-synonyms, because a misinterpretation could mean a broken glass, a damaged appliance, or a task done in a way that frustrates the user.

To cope, engineers are turning to resources that dissect how similar expressions diverge in nuance, treating them as guides for building more robust language models. Detailed references that catalog subtle distinctions between everyday phrases, such as a dictionary of confusable phrases, mirror the kind of linguistic sensitivity a robot needs when it hears “wipe down the counter” versus “scrub the counter.” The more precisely a “brain” can map those instructions to different levels of force, tools, and time, the closer it gets to behaving like a conscientious human helper rather than a clumsy automaton.

Designing robots people will actually live with

Even the smartest control system will fail if people find the robot unsettling, confusing, or visually out of place in their homes. That is why the companies training humanoid “brains” are increasingly collaborating with industrial designers and interface specialists who think about typography, color, and layout as seriously as torque and battery life. The goal is to create machines whose presence feels legible at a glance, with clear status cues, intuitive controls, and a physical form that signals capability without veering into uncanny territory.

Lessons from decades of visual communication work, including case studies on how layout and imagery influence user trust in complex systems, are quietly shaping these decisions. Proceedings that document how designers refine information displays and user journeys, such as the collected design conference proceedings, offer a playbook for making robotic interfaces that are both approachable and precise. When a humanoid’s status lights, on-device screens, and companion apps are treated as part of a coherent visual language, users are more likely to understand what the robot is doing and feel comfortable letting it operate in the background.

The mental load of delegating to machines

Handing off chores to a humanoid sounds like pure relief, but in practice it introduces a new kind of cognitive overhead: deciding what to delegate, how to phrase the request, and how much supervision is required. For many people, the mental load of managing a household is already heavy, and adding a robot into the mix risks becoming one more thing to configure and monitor. The startups building these “brains” are discovering that success depends on reducing that friction, so that asking a robot to vacuum or restock the pantry feels as effortless as thinking the thought.

Research on attention, stress, and daily functioning underscores how sensitive people are to extra demands on their working memory, especially when juggling work and family responsibilities. Clinical findings on how cognitive load and anxiety interact, like those summarized in mental health research, help explain why even small interface frictions can make a robot feel more like a burden than a helper. If a humanoid “brain” can infer routines, learn preferences, and quietly optimize its own schedule, it has a better chance of easing that load instead of adding to it.

What workers’ anxieties reveal about robot adoption

Any discussion of chore-capable humanoids quickly runs into broader worries about automation, job security, and shifting expectations at work. While domestic robots are pitched as helpers for individuals and families, the same “brains” could be deployed in offices, warehouses, and retail spaces, where the line between assistance and replacement is much sharper. I find that the way employees talk about new tools, from chatbots to scheduling software, offers a preview of how they might react when a humanoid shows up to take over the late-night inventory count or the office kitchen cleanup.

Online conversations where workers trade stories about confusing expectations, shifting responsibilities, and the quiet pressure to do more with less are already rich with hints about how robot helpers will be received. In candid threads where people describe being asked to absorb extra tasks or adapt to new systems, such as the workplace discussions on open advice forums, there is a recurring theme: tools that genuinely reduce drudgery are welcomed, but anything that feels like surveillance or stealth downsizing is met with skepticism. Startups training humanoid “brains” for chores will have to navigate that tension carefully if they want their robots to be seen as allies rather than threats.

Learning from how we already write, plan, and persuade

Behind the scenes, the teams building these systems are mining a surprisingly wide range of human practices for clues about how robots should behave. The way people structure arguments, draft instructions, and revise their own writing offers a template for how a robot “brain” might plan and re-plan its actions. Guides that challenge simplistic rules about communication, like collections of essays on misconceptions about writing, echo a broader lesson for robotics: rigid formulas rarely survive contact with real-world messiness, and flexibility is a feature, not a bug.

At the same time, the social skills that help humans influence and coordinate with one another are being translated into algorithms that decide when a robot should ask for clarification, when it should offer suggestions, and how it should respond to frustration. Manuals that break down techniques for effective persuasion and rapport-building, such as multi-part guides on influencing people, mirror the soft skills a household robot will need if it is to be trusted with sensitive tasks. A machine that can apologize gracefully, propose alternatives, or gently remind someone about a forgotten chore stands a better chance of fitting into the social fabric of a home.

From weekly routines to continuously learning robots

One of the most promising aspects of chore-focused “brains” is their potential to learn from the rhythms of everyday life rather than from one-off scripted demos. Instead of being programmed once and left static, these systems can watch how a household or workplace operates week after week, then adjust their behavior to match evolving routines. That might mean noticing that laundry piles up on Sundays, that the trash fills faster after holidays, or that certain rooms are rarely used and can be cleaned less often.

The same way people reflect on their habits in recurring updates or weekly digests, roboticists are building feedback loops that let a humanoid refine its models over time. Regular reflections on productivity and behavior, like the kind of pattern-spotting seen in weekly habit blogs, provide a conceptual template for how robots might summarize what they have learned and propose small optimizations. If a “brain” can say, in effect, “I noticed you always ask me to clear the dining table after 8 p.m., should I just do that automatically,” it begins to feel less like a static appliance and more like a partner that grows with the household.

The road ahead for humanoid chore robots

For all the excitement, the path from lab prototype to reliable household helper is still long, and the hardest problems are as much social and linguistic as they are mechanical. Startups training humanoid “brains” must prove that their systems can handle clutter, ambiguity, and human moods without constant babysitting, while also fitting into the visual and emotional landscape of real homes. That will require not only better perception and control, but also a deeper understanding of how people plan, delegate, and negotiate around shared spaces.

In my view, the most successful efforts will be those that treat robots as part of a broader ecosystem of tools, habits, and expectations rather than as isolated marvels. When chore-capable humanoids can plug into existing planning systems, respect the nuances of everyday language, and adapt to the mental and emotional bandwidth of the people around them, they will stop feeling like science projects and start feeling like infrastructure. The journey from novelty to necessity will not be driven by spectacle, but by the quiet, cumulative relief of a thousand small tasks handled well, week after week, by a machine that has finally learned how humans really live.

More from MorningOverview