Astronomers have identified a star locked in a tight dance with a black hole that appears to be far quieter than theory says it should be, challenging long-held assumptions about how these extreme objects feed and flare. Instead of blazing with the usual fireworks of high-energy radiation, this system seems to be breaking the standard rules of black hole behavior while still tearing into its stellar companion. The discovery is forcing researchers to rethink how invisible black holes can hide in plain sight and how many more might be lurking undetected in our own cosmic backyard.

At the heart of the puzzle is a black hole that appears to be stripping material from a nearby star without producing the bright, chaotic signatures astronomers typically expect from such violent encounters. That mismatch between theory and observation is more than a curiosity, because it hints that the census of black holes in the universe could be badly incomplete and that some of the most dramatic stellar deaths may be unfolding in ways current models do not yet capture.

What makes this black hole–star pairing so strange

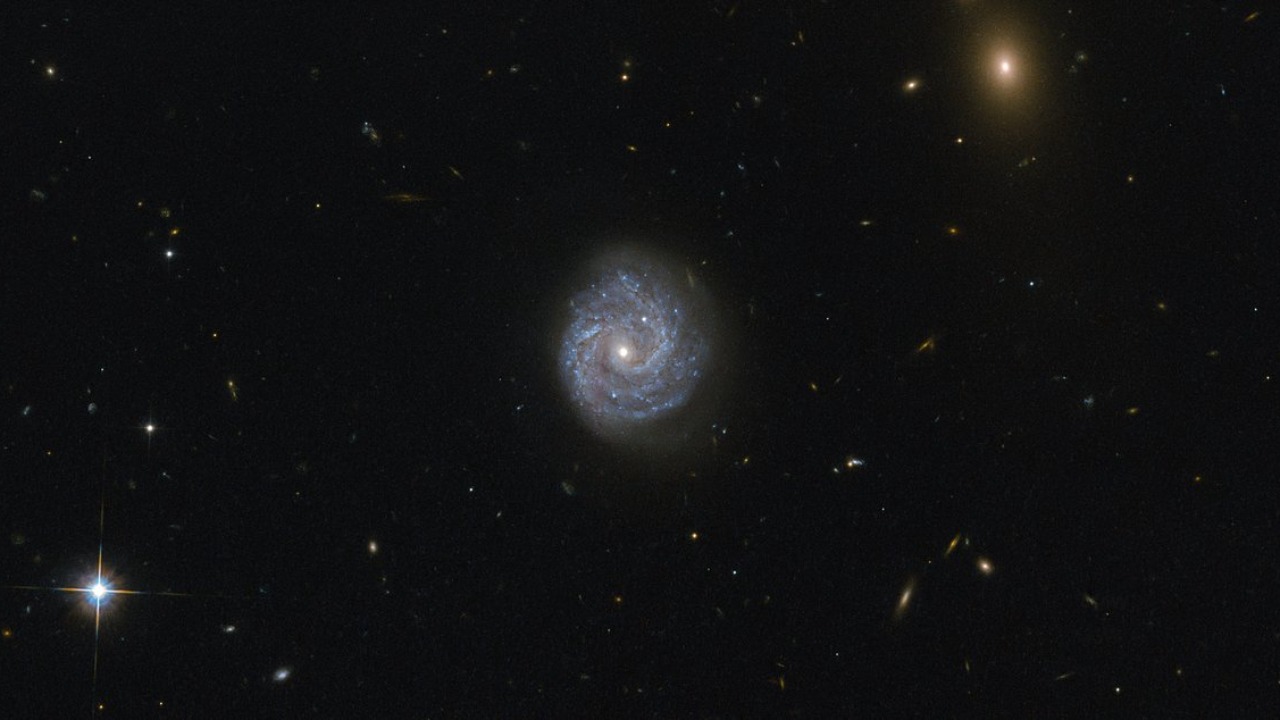

In the standard picture, when a star strays too close to a black hole, gravity pulls it apart and funnels the debris into a hot, swirling accretion disk that lights up in X-rays and other high-energy wavelengths. The newly reported system appears to follow only half of that script, with a star clearly under gravitational assault but a black hole that remains unusually subdued in its emissions, a combination that has led researchers to describe it as a rule breaker. Reporting on the event highlights how the black hole seems to be shredding its stellar partner in a way that does not match the expected pattern of a classic tidal disruption flare, a discrepancy that has been described as “truly extraordinary” in coverage of the puzzling interaction.

Part of what makes the system so intriguing is that the star appears to be on a bound orbit rather than a one-time fatal plunge, suggesting a long-running relationship instead of a single catastrophic encounter. In a typical tidal disruption, a star is torn apart in one pass and its remains quickly spiral inward, but here the observations point to a more drawn-out process in which the star survives repeated close approaches while still losing mass. That kind of ongoing, relatively quiet stripping challenges the usual categories astronomers use to describe black hole feeding and raises the possibility that similar systems have been overlooked because they do not fit the standard observational templates.

How black holes are supposed to behave when they eat

To understand why this system is so disruptive to expectations, it helps to recall the basic physics of black holes and their meals. In the conventional framework, a black hole is defined by an event horizon, a boundary beyond which not even light can escape, and by the intense gravitational field that shapes everything nearby. When gas or stellar material falls toward that horizon, it accelerates and heats up, forming a bright accretion disk that can outshine entire galaxies, a process that is central to the way introductory notes on black hole structure and accretion describe these objects.

In that standard picture, the more aggressively a black hole feeds, the louder it should appear across the electromagnetic spectrum, especially in X-rays and ultraviolet light. Stellar-mass black holes in binary systems, for example, typically reveal themselves through bright, variable X-ray outbursts as they siphon gas from a companion star, while supermassive black holes at galactic centers can power quasars that are visible across billions of light-years. The newly reported system, by contrast, seems to be consuming stellar material without producing the expected blaze, which is why astronomers are treating it as a rare chance to test where the textbook model of accretion breaks down.

Clues from a star under attack

What anchors the interpretation of this system is the unmistakable evidence that the star itself is in trouble. Observers have reported signatures consistent with a star being stretched and stripped by a compact object, including changes in brightness and spectral features that point to hot, fast-moving gas. In video explainers that have circulated widely, the event is framed as a black hole that has “broken the rules” by destroying a star in an unexpected way, a narrative that reflects how the system has been presented in public-facing coverage such as a widely shared clip describing the encounter.

Those public narratives echo the scientific tension behind the scenes, where researchers are trying to reconcile the star’s apparent distress with the black hole’s relative quiet. If the star is losing mass on each close pass, then there must be a mechanism for that material to either fall into the black hole or be flung away, yet the usual observational signatures of either outcome are muted. That mismatch suggests that the geometry of the system, the spin of the black hole, or the properties of the infalling gas may be suppressing the usual fireworks, offering a rare laboratory for testing how subtle changes in conditions can dramatically alter the visible outcome of a black hole feeding event.

From rockets to quiet black holes: a longer arc of exploration

Although this discovery is rooted in cutting-edge astrophysics, it also fits into a much longer story about how humans have learned to probe extreme environments far beyond Earth. The ability to detect a relatively faint, rule-bending black hole system depends on decades of investment in rocketry, space-based observatories, and the engineering culture that grew up around them, a lineage that can be traced through detailed historical accounts of early launch vehicles and crewed missions such as those documented in NASA’s multi-volume histories of rockets and people. The same technologies that once lifted astronauts into orbit now support sensitive telescopes that can monitor distant galaxies for subtle flickers of light.

That continuity matters because the instruments used to spot a quiet black hole nibbling at a star are the product of iterative advances in detectors, data transmission, and mission design. X-ray and optical observatories rely on stable platforms, precise pointing, and robust communications infrastructure, all of which were refined through earlier generations of spaceflight. When astronomers talk about a black hole that appears to be breaking the rules, they are leaning on a technological foundation that has steadily expanded the range of phenomena that can be observed, from the first crude satellite measurements to today’s multiwavelength surveys that can catch a star in the act of being torn apart.

AI’s growing role in catching cosmic oddities

The strange behavior of this black hole–star pair also highlights how artificial intelligence is becoming central to modern astronomy. Large sky surveys now generate torrents of data that are impossible for humans to sift through manually, so researchers increasingly rely on machine learning systems to flag unusual transients and outliers. The discovery of an exploding star that appears to be under attack from a black hole, for example, has been cited as a case where AI tools helped astronomers identify a potentially major event by scanning vast datasets for the right combination of brightness changes and spectral clues, as described in reporting on how AI assists in finding black hole–star interactions.

Behind those headline-grabbing results lies a quieter revolution in how models are trained, evaluated, and deployed. Researchers benchmark different AI systems on complex tasks, track their performance across multiple metrics, and refine their architectures to better handle noisy, real-world data, a process that can be seen in technical records of evaluation runs such as the logged results for model scoring on benchmark suites. The same discipline that goes into ranking language models or vision systems is now being applied to astrophysical pipelines, where the goal is to ensure that rare, rule-breaking events are not lost in the noise of more ordinary cosmic activity.

Data, privacy, and the new universe of information

As telescopes and AI systems become more capable, the volume and sensitivity of the data they produce raise questions that go beyond astrophysics. The infrastructure that supports modern sky surveys is part of a broader digital ecosystem in which information about people, devices, and environments is constantly collected, analyzed, and stored. Debates over how to manage that deluge, and how to protect individual privacy in a world where data can be copied and recombined at scale, have been shaped by influential analyses of the digital revolution that examine how information can be “blown to bits” in ways that challenge traditional notions of control, as explored in detailed discussions of data, privacy, and digital life.

Although astronomical observations do not typically involve personal data, the tools and platforms used to process them often sit on shared infrastructure with more sensitive applications, and the norms that govern one domain can spill over into another. The same cloud services that host sky survey archives may also store medical records or financial transactions, and the same machine learning frameworks that help identify a quiet black hole can be repurposed for surveillance or targeted advertising. Recognizing those overlaps is part of treating astronomy as one thread in a much larger tapestry of data-intensive science, where questions about access, transparency, and accountability are increasingly central.

Learning to read anomalies, from stars to sentiment

Interpreting a rule-breaking black hole system is, at its core, an exercise in pattern recognition and anomaly detection, skills that are also central to how AI systems learn to parse human language and behavior. In natural language processing, for example, models are trained to identify which words in a sentence carry sentiment or refer to specific aspects of a product, a task that is formalized in teaching materials on aspect term extraction and sentiment analysis. Just as those systems must distinguish between routine phrases and meaningful signals, astronomers must separate ordinary variability in a star’s light from the telltale signs that it is being distorted by a nearby black hole.

The technical underpinnings of that work often involve low-level tools and formats that are invisible to most observers but crucial for reproducibility and collaboration. Version-controlled code snippets, configuration files, and binary formats are shared and dissected in developer communities, where detailed examples such as a binary parsing walkthrough can serve as templates for handling complex data structures. In astronomy, similar practices help teams manage instrument calibrations, simulation outputs, and analysis scripts, ensuring that when a strange system like a quiet black hole–star pair is flagged, others can independently verify the signal and test alternative explanations.

Culture, collaboration, and the future of “quiet” black holes

Behind the equations and code, discoveries like this one are also shaped by the cultures of the teams that pursue them. International collaborations bring together researchers with different disciplinary backgrounds, institutional norms, and communication styles, and those differences can influence everything from how anomalies are prioritized to how credit is assigned. Studies of cross-cultural interaction have long noted how misunderstandings can arise when expectations clash, but they also emphasize the creative potential of diverse perspectives, a theme explored in depth in analyses of when cultures collide in global work.

In the context of a rule-bending black hole, that diversity can be a strength, because it encourages teams to question assumptions and entertain multiple interpretations of the same data. One group might focus on the orbital dynamics of the star, another on the microphysics of accretion flows, and a third on the statistical likelihood that similar systems have been missed. As more telescopes come online and AI tools grow more sophisticated, the ability to integrate those perspectives will shape how quickly the field can move from surprise to understanding, and how well it can map the hidden population of quiet black holes that may be reshaping their surroundings in ways that only become visible when a nearby star starts to break the rules.

More from MorningOverview