Astronomers have identified a tightly bound pair of stars that are spiraling toward a catastrophic merger, turning a distant stellar system into a natural laboratory for testing gravity at its most extreme. The doomed binary is losing energy so quickly that its orbit is shrinking in real time, giving researchers a rare chance to watch Einstein’s theory of general relativity face a fresh and unforgiving trial.

By tracking how fast the two stars circle each other, how their light flickers and how their orbit decays, I can see scientists probing whether gravity behaves exactly as Einstein predicted or whether subtle deviations emerge under crushing densities and blistering speeds. The stakes reach far beyond one exotic system: the outcome will shape how we interpret gravitational waves, model stellar explosions and even estimate the age and fate of some of the most violent events in the universe.

The strange lives of doomed binary stars

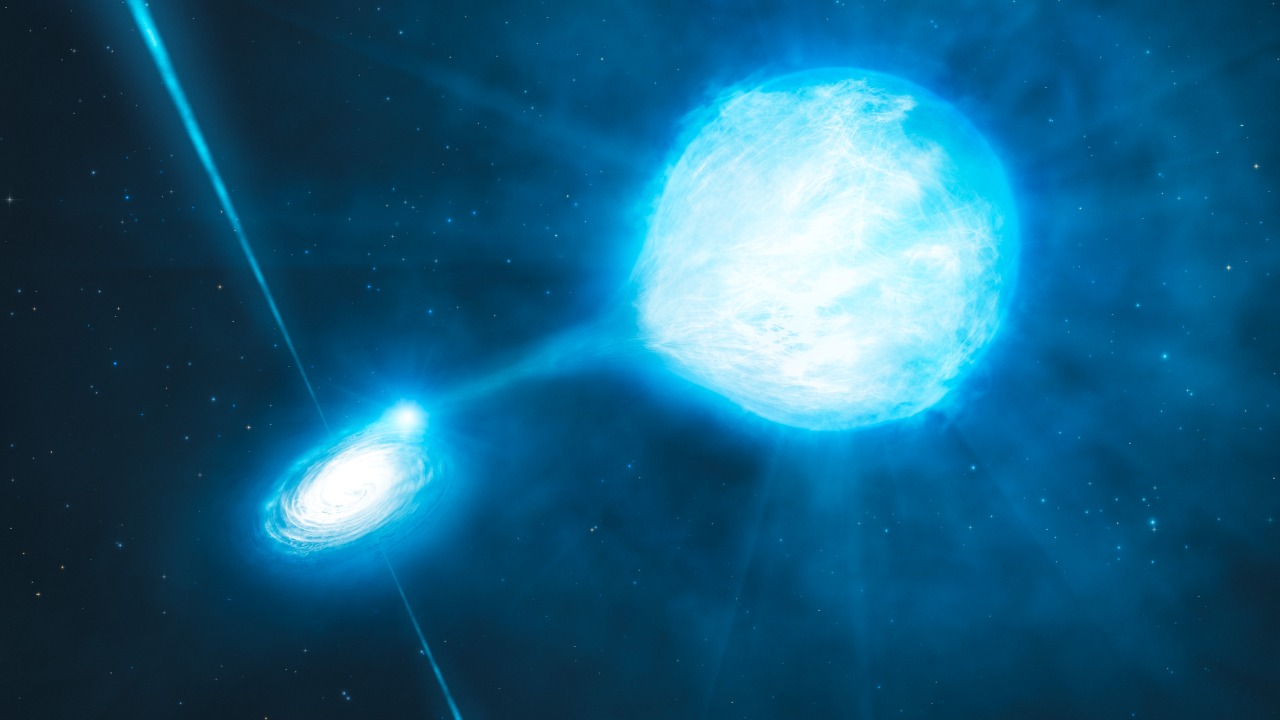

Binary stars are common in the Milky Way, but only a small fraction are on a collision course that will end in a single, violently transformed object. In this newly analyzed system, the two stars orbit so closely that their mutual gravity strips material from their outer layers and converts orbital energy into heat and radiation. I see that process as a slow-motion death spiral, where each orbit tightens the noose, speeding up the dance and amplifying the stresses on both stars.

What makes this pair scientifically precious is not just its fate but its timing. The orbit is decaying fast enough that astronomers can measure changes over human timescales, rather than inferring them from ancient remnants. That means the system functions as a live experiment in strong gravity, letting researchers compare the observed orbital decay with the precise rate predicted by general relativity for a compact binary that is radiating energy away in the form of gravitational waves, as described in detail in the report on spiraling stars.

How a tightening orbit turns into a gravity test

Einstein’s theory says that when two massive objects orbit each other, they should emit ripples in spacetime that carry energy away, causing the orbit to shrink. For decades, that prediction was tested indirectly by timing the pulses of neutron star binaries and watching their orbits decay at exactly the rate relativity demands. In this new stellar pair, I see astronomers applying a similar logic, but with different kinds of stars and a different set of observational tools, to check whether the same rules hold in a fresh regime.

By measuring the orbital period with high precision and tracking how it changes over years, researchers can calculate how much energy the system is losing. They then compare that loss with the theoretical energy carried off by gravitational radiation from a binary with the observed masses and separation. If the decay rate matches the relativistic prediction within the uncertainties, it tightens the constraints on any alternative gravity theories that would tweak how strongly spacetime ripples in such a system, a point that is central to the analysis of the rapidly shrinking orbit in the documented binary system.

Watching light reveal invisible forces

Because the stars are so close, their mutual tug distorts their shapes and modulates their brightness, turning the system into a kind of cosmic heartbeat monitor. Each orbit produces subtle changes in the light curve as one star eclipses the other or as tidal forces stretch their surfaces. I see observers using those variations to infer the stars’ sizes, temperatures and orbital geometry, which in turn feed into the gravity tests by sharpening estimates of mass and separation.

Spectroscopic measurements add another layer of insight, capturing how the stars’ spectral lines shift as they race toward and away from Earth. Those Doppler shifts reveal their velocities and allow astronomers to reconstruct the full three-dimensional orbit. When combined with the timing of eclipses and brightness dips, the data set becomes rich enough to pin down the system’s parameters with the precision needed to confront general relativity, a strategy that underpins the detailed orbital modeling described for the spiraling pair.

From stellar death spiral to future gravitational waves

Although the stars have not yet merged, their fate is sealed by the relentless loss of orbital energy. As the separation shrinks, the orbital period will shorten, the velocities will climb and the gravitational radiation will grow stronger. I see this system as a preview of the kind of compact binaries that, once they evolve further, could become sources of gravitational waves detectable by future space-based observatories that are tuned to lower frequencies than current ground-based detectors.

By studying the system now, astronomers can refine models of how such binaries evolve, how quickly they shed angular momentum and how their internal structures respond to tidal forces. Those models feed directly into predictions of merger rates and waveforms for upcoming gravitational-wave missions. The detailed characterization of the doomed pair’s current state, as laid out in the observational campaign on the doomed binary, helps anchor those long-term forecasts in real data rather than purely theoretical scenarios.

Einstein’s theory under pressure

General relativity has survived every experimental test so far, from the precession of Mercury’s orbit to the timing of pulsars and the direct detection of gravitational waves from black hole mergers. Yet I see theorists continuing to push for new tests in different environments, because any deviation, however small, could point toward a deeper theory that unifies gravity with quantum mechanics. A close binary of ordinary stars, on the brink of coalescence, offers a complementary arena to the ultra-compact neutron star systems that have dominated past precision tests.

In this case, the question is not whether relativity fails spectacularly but whether the data leave room for subtle corrections that might emerge at certain densities or orbital speeds. By comparing the observed orbital decay, light-curve distortions and spectroscopic velocities with the predictions of Einstein’s equations, researchers can either tighten the noose on alternative models or flag anomalies that demand further scrutiny. The careful cross-checks described for the spiraling stars show how seriously the community takes the task of turning a picturesque stellar drama into a rigorous test of fundamental physics.

What the merger could leave behind

When the two stars finally collide, the outcome will depend on their masses, compositions and how much mass they have already traded during their long interaction. I see several possibilities: a single, more massive star that may spin rapidly and shed material in a powerful outburst, a compact object such as a white dwarf, or in more extreme cases a precursor to a supernova. Each scenario carries its own observational signatures, from sudden brightening to the appearance of unusual chemical elements in the surrounding space.

Although the exact end state of this particular system remains uncertain, the current observations already constrain the range of plausible futures. By tracking how mass transfer proceeds and how the orbital period evolves, astronomers can narrow down which evolutionary pathways are consistent with the data. The detailed monitoring of the doomed pair described in the study of the doomed binary is laying the groundwork for predicting not only when the final act might occur but also what kind of object will emerge from the wreckage.

Why one distant binary matters for everyday physics

It might seem that the fate of a remote pair of stars has little to do with life on Earth, but I see a direct line from such systems to the technologies and models that shape our daily world. The same equations of gravity that govern the binary’s orbit also guide the trajectories of GPS satellites, the paths of interplanetary probes and the timing of signals that underpin global communications. Every time astronomers confirm that general relativity holds in a new regime, they reinforce the foundations of those practical applications.

At the same time, any hint of deviation would ripple through cosmology and high-energy physics, potentially altering our understanding of dark matter, dark energy and the ultimate fate of the universe. That is why the meticulous work on the spiraling stars carries weight far beyond the astrophysics community. By turning a doomed binary into a precision instrument for testing gravity, researchers are not only chronicling a spectacular cosmic demise but also probing the limits of one of the most successful theories in science.

More from MorningOverview