Buried beneath the ice of northwest Greenland, a Cold War outpost once designed for nuclear war planning is reemerging in public view, thanks to satellite imagery and a warming climate. The secretive installation, known as Camp Century, was built to test whether the United States could hide nuclear missiles under the ice sheet and is now drawing renewed scrutiny as its frozen cover thins. What was once a covert military experiment is turning into a very contemporary problem about nuclear waste, climate risk, and geopolitical responsibility.

As I trace the story of this hidden base, I keep coming back to how a project conceived in the shadow of the Soviets is now being rediscovered in an era defined by climate science and satellite surveillance. The same tunnels that once symbolized Cold War ingenuity are now a case study in what happens when yesterday’s secrets collide with today’s environmental realities.

The Cold War vision beneath Greenland’s ice

The starting point for understanding Camp Century is the strategic logic of the Cold War, when the United States sought ways to keep nuclear forces survivable in the event of a surprise attack. During the Cold War, the U.S. built a military base under the ice in Greenland, hidden from the Soviets, roughly 150 miles inland from the coast. Officially, it was presented as a research station, but in reality it was a test bed for a far more ambitious concept: a buried network of launch sites that could host nuclear-armed missiles under the ice.

The codename for that plan was Project Iceworm, a United States Army program that envisioned thousands of miles of tunnels carved into the ice sheet. Camp Century was described at the time as a demonstration of polar engineering, but its real purpose was to test whether the ice could support a mobile missile grid in case of nuclear war. The base’s location under the ice, and its distance from populated areas, were central to the idea that nuclear weapons could be both concealed and protected in the Arctic.

Camp Century, “City Under the Ice”

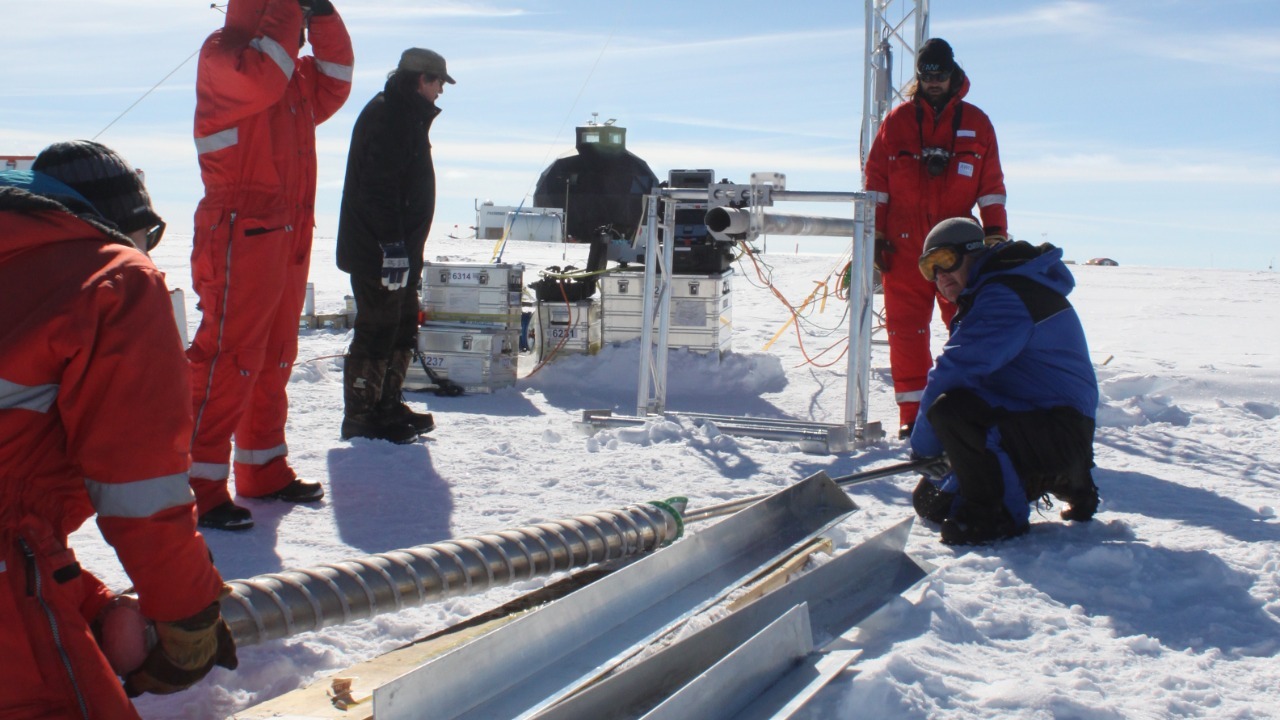

Camp Century itself was a feat of mid‑20th century engineering, a lattice of snow tunnels and prefabricated structures buried beneath roughly 100 feet of ice. About Camp Century, reporting notes that it was commissioned by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and built by the Army Corps of Engineers, which cut long trenches into the ice and covered them with arched roofs before backfilling with snow to create enclosed corridors. The project, commissioned under President Dwight Eisenhower and executed by the Army Corps of Engineers, was as much a demonstration of American technological prowess as it was a military experiment.

In recent coverage, Camp Century is often referred to as a “City Under the Ice,” a phrase that captures both its scale and its eerie isolation. NASA has shared an image of this defunct Cold War‑era military base, highlighting how the installation, once hidden from view, can now be picked out in modern satellite data. That NASA image underscores how a base once designed to be invisible to enemy bombers is now plainly visible from orbit, its legacy preserved in the ice and in the data.

Project Iceworm’s nuclear ambitions

To grasp why Camp Century matters today, I have to look beyond the base itself to the larger scheme it supported. Project Iceworm was not a modest research proposal, but a plan to deploy a vast network of mobile nuclear missiles under the Greenland ice sheet. The Cold War nuclear missiles concept relied on the idea that launch sites could be constantly shifted through tunnels, making them nearly impossible for the Soviets to target in a first strike.

According to historical accounts, the United States Army saw the ice sheet as both a shield and a camouflage layer, with Camp Century serving as the prototype for how such a system might work in practice. The “Project Iceworm” concept depended on stable ice and predictable conditions, assumptions that climate science now shows were far more fragile than planners understood at the time. Even though the full missile network was never realized, the ambition behind it explains why the base was built with such secrecy and why its remnants still carry nuclear implications.

From secret weapons lab to climate science archive

What makes Camp Century unusual among Cold War relics is that it doubled as a scientific outpost, leaving behind a trove of environmental data that researchers still mine today. During the Cold War, the U.S. built a military base under the ice in Greenland, hidden from the Soviets, but scientists working there also drilled deep into the ice sheet and extracted cores that captured thousands of years of climate history. Those cores, taken from ice about 150 miles inland, later became a pivotal resource for understanding how the Arctic responds to warming.

Recent reporting has emphasized that the base’s scientific legacy is now as important as its military past. A detailed account of how the installation evolved notes that the ice cores and other samples collected at Camp Century helped establish early baselines for Arctic temperatures and snowfall, data that modern researchers compare with satellite records and newer fieldwork. That dual identity, as both a covert military site and a climate science archive, is one reason the base continues to attract attention in Greenland and beyond.

Melting ice and the threat of buried nuclear waste

The most urgent question now is not how Camp Century once operated, but what happens as the ice that entombs it continues to melt. Earlier assessments warned that Greenland’s receding icecap could eventually expose the top‑secret U.S. nuclear project, raising the possibility that fuel, chemicals, and other contaminants might be released into the environment. Reporting from Sep 26, 2016 described how, once the ice begins to melt in earnest around the site, the question of who is responsible for the clean‑up, already the subject of discussion, will become impossible to ignore. As one analysis put it, once the ice starts to give way, it will be necessary to settle questions of mutual security and environmental liability linked to Once‑secret installations like Camp Century.

More recent coverage has sharpened the stakes by quantifying what is still buried at the site. Although Camp Century is uninhabited today, it does contain over 47,000 g of nuclear waste that was never removed, along with other contaminants that remain sealed in the ice. As long as the ice sheet stays cold and stable, that material is effectively locked away. But as warming accelerates, scientists and policymakers are increasingly concerned that meltwater could mobilize those substances, turning a long‑forgotten weapons project into a slow‑moving pollution crisis.

NASA’s rediscovery and the power of satellite eyes

The renewed focus on Camp Century is not only about climate models and archival documents, it is also about what can now be seen from space. In Nov 24, 2024, NASA shared an image of the lost U.S. military base, highlighting how modern sensors can pick out subtle surface features that betray the presence of buried structures. That NASA image was initially puzzling even to experts, who had to reconcile the patterns on the ice with historical maps and records of the base’s layout.

Coverage from Nov 26, 2024 framed the rediscovery as a reminder that the Arctic still holds hidden infrastructure, some of it tied directly to nuclear strategy. The report, dated Nov 26, 2024, described how the “City Under the Ice” label has taken on new meaning now that high‑resolution imagery can reveal structures deep within the tundra and ice sheet. By combining those visuals with historical accounts of how the base was commissioned by President Dwight Eisenhower and built by the Army Corps of Engineers, the “City Under the Ice” narrative has shifted from Cold War secrecy to a case study in how satellites can surface buried history.

Greenland, local stakes, and unresolved responsibility

For Greenland itself, the story of Camp Century is not an abstract historical curiosity, but a live question about sovereignty, environmental risk, and who pays for any future clean‑up. The base sits within Greenland’s territory, yet it was built and operated by the United States under Cold War security arrangements that did not anticipate long‑term climate change. As the ice sheet that covers much of northwest Greenland continues to thin, local authorities and residents are left to weigh the risks of contamination against the political realities of pressing a powerful ally for remediation.

Earlier reporting from Sep 26, 2016 made clear that discussions were already underway about how to handle the eventual exposure of the site, but those talks did not produce a definitive agreement on responsibility. Since then, each new scientific assessment of Greenland’s receding icecap has added urgency to the question of who will monitor, contain, and, if necessary, remove the legacy materials from this top‑secret U.S. nuclear project. The unresolved nature of that responsibility, set against the backdrop of a rapidly changing Arctic, is what turns Camp Century from a historical footnote into a test of how nations confront the environmental debts of their Cold War past.

What a “secret base” means in the satellite era

When I look at the arc of Camp Century’s story, from covert missile testbed to climate science archive to potential pollution source, it is hard to ignore how much the meaning of secrecy has changed. In the 1960s, planners assumed that burying a base under the ice in Greenland would keep it hidden from adversaries and the public alike. Today, high‑resolution satellite imagery, open‑source analysis, and detailed historical research have combined to make that same base one of the most scrutinized sites on the ice sheet, a place where the legacies of nuclear strategy and environmental change intersect in plain view.

The phrase “secret US nuclear base” still has rhetorical power, but in practice Camp Century is now less a secret than a shared problem that spans generations and borders. Its tunnels, once carved to host weapons aimed at the Soviets, now hold 47,000 g of nuclear waste and other contaminants that future Greenlanders may have to manage. As climate models project continued melting and satellite images track every subtle shift in the ice, the real test will be whether the governments involved can move from Cold War habits of silence to a more transparent reckoning with what was left behind in the frozen north.

More from MorningOverview