Multicellular cyanobacteria do something strikingly sophisticated with their DNA, toggling key genes on and off as day turns to night so different cells can specialize without starving the colony of energy. That genetic choreography lets them pull off a biochemical balancing act that single cells cannot manage, splitting the work of photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation across time and space. I see that daily flip as a window into how simple microbes evolved complex teamwork long before plants and animals appeared.

From single cells to coordinated filaments

To understand why gene switching in cyanobacteria matters, I start with their basic lifestyle. These microbes are among the oldest photosynthetic organisms on Earth, and some species live as chains of cells rather than as isolated individuals. In filamentous forms, neighboring cells share resources and signals, turning a string of microbes into a coordinated unit that behaves more like a tiny tissue than a loose collection of clones. That shift from solitary to communal life sets the stage for the day–night division of labor that researchers are now dissecting in detail, including how specific genes rise and fall with the light cycle in multicellular strains such as Anabaena and Nostoc [source].

What makes these filaments especially intriguing is that not every cell does the same job. Some cells focus on capturing sunlight and producing carbohydrates, while others specialize in fixing atmospheric nitrogen into usable forms, a process that is poisoned by oxygen. That incompatibility forces the colony to solve a basic problem of metabolism: how to generate oxygen through photosynthesis and still run oxygen-sensitive nitrogenase enzymes. The solution, as multiple studies of filamentous cyanobacteria have shown, is to combine spatial specialization along the filament with temporal control across the day–night cycle, so gene expression patterns shift in sync with both cell type and time of day [source].

Why photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation cannot share the same moment

The core conflict driving this genetic flip is chemical. Oxygenic photosynthesis splits water and releases O2, while nitrogen fixation relies on nitrogenase, an enzyme complex that is irreversibly inactivated by oxygen. If a single cell tried to run both processes at full tilt at the same time, it would sabotage its own nitrogen supply. In unicellular cyanobacteria, one workaround is to fix nitrogen only at night, when photosynthetic oxygen production drops, and to stockpile carbohydrates from the day to fuel that nocturnal activity. Filamentous species add another layer of complexity, using specialized cells that suppress photosystem II and ramp up nitrogenase, but even in those filaments, the timing of gene expression still tracks the light–dark cycle in a precise rhythm documented in controlled culture experiments [source].

In practice, that means the same genome encodes two incompatible metabolic states that must be separated in time, space, or both. Researchers who followed transcription profiles across 24-hour cycles in multicellular cyanobacteria found that genes for photosynthetic machinery peak during the light period, while nitrogen fixation genes surge in the dark or in heterocysts that are shielded from oxygen. The pattern is not a simple on–off switch, but a coordinated wave of expression that aligns with environmental cues such as light intensity and internal signals like redox status. Those studies show that the daily gene flip is not just a passive response to sunrise and sunset, but an active program that anticipates the coming phase and prepares the cells for the next metabolic regime [source].

Heterocysts: permanent specialists in a changing day

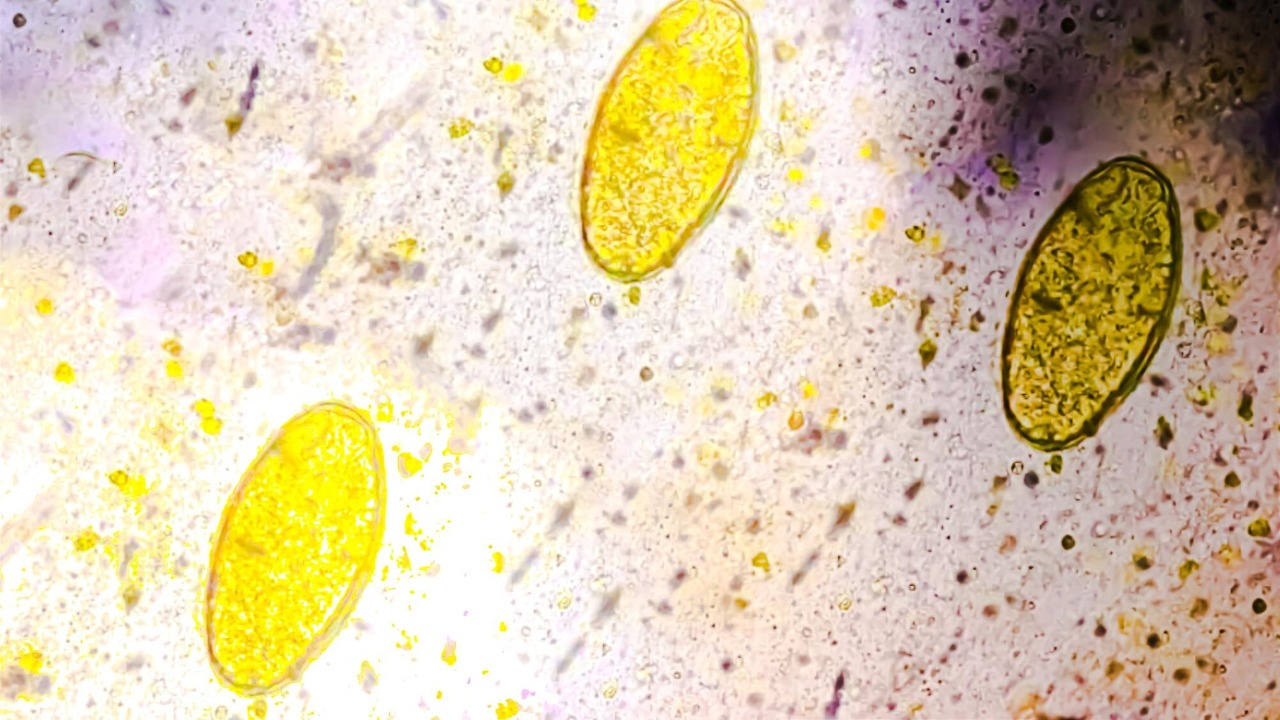

In many filamentous cyanobacteria, the most visible sign of division of labor is the heterocyst, a thick-walled cell that commits to nitrogen fixation and largely abandons oxygenic photosynthesis. Once a vegetative cell differentiates into a heterocyst, it does not revert, which makes the decision essentially permanent for that cell. I see that as a striking example of how a simple microbe can lock in a specialized fate, echoing the way animal cells commit to becoming neurons or muscle. Genetic and imaging work has shown that heterocysts form at semi-regular intervals along the filament, creating a pattern where nitrogen-fixing cells are spaced among photosynthetic neighbors that feed them carbohydrates in exchange for fixed nitrogen [source].

Even within this spatial pattern, the day–night cycle still matters. Heterocysts maintain nitrogenase activity across the diel cycle, but the expression of supporting genes and transporters shifts with light availability, while vegetative cells modulate photosynthetic gene expression and carbon export. Transcriptomic analyses across multiple time points have revealed that heterocysts and vegetative cells share a core circadian program, yet overlay it with cell-type-specific gene sets that rise and fall at different phases. That layered regulation lets the filament keep nitrogen fixation relatively steady while still tuning energy production and metabolite exchange to the external light regime, a strategy that appears in several independently studied strains of multicellular cyanobacteria [source].

Circadian clocks wired into microbial teamwork

The precision of this daily gene choreography points to an internal clock, not just a direct reaction to light. Cyanobacteria are famous for having one of the best characterized prokaryotic circadian systems, built around the KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC proteins that generate a roughly 24-hour rhythm in phosphorylation state. In multicellular strains, that clock does not tick in isolation inside each cell. Instead, evidence from clock gene mutants and reporter constructs suggests that the circadian machinery is integrated with signals that coordinate along the filament, so the entire chain keeps roughly the same phase even as individual cells specialize. When researchers disrupted key clock components, they saw misaligned expression of photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation genes, which in turn reduced growth under natural light–dark cycles [source].

I find that coupling between circadian timing and multicellular organization especially revealing. It implies that the evolution of a robust clock did not just help single cells anticipate sunrise, it also created a temporal framework for dividing labor across a community. Studies that tracked fluorescent reporters under constant light have shown that the clock continues to drive oscillations in gene expression even without external cues, and that neighboring cells in a filament tend to stay synchronized. That internal rhythm then gates when certain genes can be turned on, so nitrogenase peaks during the subjective night and photosystem components during the subjective day, a pattern that persists across several cycles in laboratory conditions [source].

Gene circuits that flip with the light

At the level of individual genes, the day–night flip looks like a carefully wired circuit. Promoters of photosynthesis-related genes often carry binding sites for transcription factors that are activated by light or by the oxidized state of the photosynthetic electron transport chain. In contrast, nitrogen fixation genes are controlled by regulators that respond to low oxygen, high carbon reserves, and clock-controlled signals. When scientists mapped these regulatory networks in multicellular cyanobacteria, they found overlapping modules where the same transcription factor could repress one set of genes while activating another, depending on the time of day and cell type. That architecture creates sharp transitions in expression without requiring a separate regulator for every gene, a design that shows up repeatedly in genome-wide binding and expression datasets [source].

One striking example involves the interplay between NtcA, a global nitrogen regulator, and HetR, a master regulator of heterocyst differentiation. NtcA activity rises when combined nitrogen is scarce, promoting expression of nitrogenase components and of hetR, which in turn drives the formation of heterocysts at specific positions along the filament. Both regulators are themselves influenced by the circadian clock and by metabolites that accumulate during the day, such as 2-oxoglutarate. Time-resolved ChIP-seq and RNA-seq experiments have shown that NtcA and HetR binding to target promoters waxes and wanes across the diel cycle, aligning the onset of nitrogen fixation with periods when oxygen levels are lower and carbon supplies are sufficient to fuel the energy-intensive process [source].

Ecological payoffs of temporal gene partitioning

The genetic flip between day and night is not just a molecular curiosity, it shapes how cyanobacterial communities function in real ecosystems. In lakes, reservoirs, and coastal waters, filamentous cyanobacteria often dominate late-summer blooms, where they can both fuel and destabilize food webs. Their ability to fix nitrogen at night or in heterocysts gives them an edge when dissolved nitrate and ammonium are depleted, letting them continue to grow while competitors stall. Field measurements that combined metatranscriptomics with environmental monitoring have shown that nitrogen fixation gene expression in bloom-forming filaments peaks during the dark period, while photosynthesis genes dominate during daylight, mirroring the patterns seen in culture and confirming that the day–night partitioning operates in natural settings [source].

That temporal specialization also affects how cyanobacteria interact with other microbes. By releasing fixed nitrogen and organic carbon at different times of day, filaments can create rhythmic resource pulses that neighboring bacteria and phytoplankton exploit. Some studies of microbial mats and stratified water columns have documented daily cycles in community composition and activity, with heterotrophic bacteria ramping up expression of transporters and catabolic enzymes shortly after cyanobacteria release exudates. I see those patterns as evidence that the cyanobacterial clock and its gene-flipping circuits ripple outward, structuring entire microbial ecosystems around a shared 24-hour rhythm anchored in the metabolism of these ancient phototrophs [source].

Lessons for the evolution of complexity and future applications

When I look at multicellular cyanobacteria toggling genes between day and night, I see a living model of how simple organisms can bootstrap complexity from basic constraints. The incompatibility between oxygenic photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation forced these microbes to separate tasks in time and space, and in solving that problem they evolved stable cell types, long-range coordination, and integrated circadian control. Those traits echo hallmarks of more elaborate multicellular life, suggesting that environmental cycles and metabolic conflicts may have been powerful drivers of biological innovation. Comparative genomic work that traces the distribution of heterocysts, clock components, and nitrogen fixation genes across cyanobacterial lineages supports the idea that these features were assembled stepwise, with temporal regulation often preceding full spatial specialization [source].

The practical implications are just starting to come into focus. Synthetic biologists are already borrowing cyanobacterial promoters and clock elements to build gene circuits that respond predictably to light–dark cycles, with an eye toward engineering microbes that produce biofuels or high-value chemicals during the day and perform maintenance or stress responses at night. Agricultural researchers are also watching these systems closely, since understanding how cyanobacteria manage nitrogen fixation without poisoning their own enzymes could inform efforts to transfer similar capabilities into crop-associated microbes. Early proof-of-concept projects that transplant clock-controlled regulators into heterologous hosts show that it is possible to recreate diel expression patterns, although matching the robustness of native cyanobacterial circuits remains a challenge [source].

More from MorningOverview