NASA’s Swift space telescope is running out of altitude, but a privately funded spacecraft is being readied to push it higher and keep its science going into the next decade. The planned 2026 servicing flight would mark the first time a commercial mission physically boosts a government astronomy satellite, turning a looming reentry into a test case for a new kind of orbital life extension.

If it works, the maneuver could reshape how the United States manages aging observatories at a time when budgets are tight and new flagship missions are already straining the system. I see this experiment as a bellwether for whether public science can safely lean on private hardware without sacrificing reliability or long term planning.

Swift is slipping toward Earth, and the clock is ticking

Swift was launched to hunt gamma ray bursts, the brief but powerful flashes that signal some of the most violent events in the universe, and it has been quietly circling Earth for years while feeding astronomers a steady stream of discoveries. Its low orbit, however, is gradually decaying, and without intervention the spacecraft will eventually reenter the atmosphere and burn up, taking its unique observing capabilities with it. That looming loss is what set the stage for a commercial company to propose a direct rescue rather than watch a still productive telescope die early.

Reporting on the mission describes Swift’s altitude as low enough that drag is no longer a distant concern but a near term operational limit, with engineers warning that the telescope is “about to fall out of the sky” if nothing is done to raise its orbit. The private team behind the planned servicing flight has framed the situation in stark terms, arguing that the observatory’s remaining lifetime can be dramatically extended with a single well targeted push, a claim that matches the urgency highlighted in technical commentary on how quickly a low Earth orbit can decay once it drops below a safe threshold, as detailed in analyses of the telescope’s trajectory and its shrinking margin for error in sources such as about to fall out of the sky.

A first of its kind commercial boost in 2026

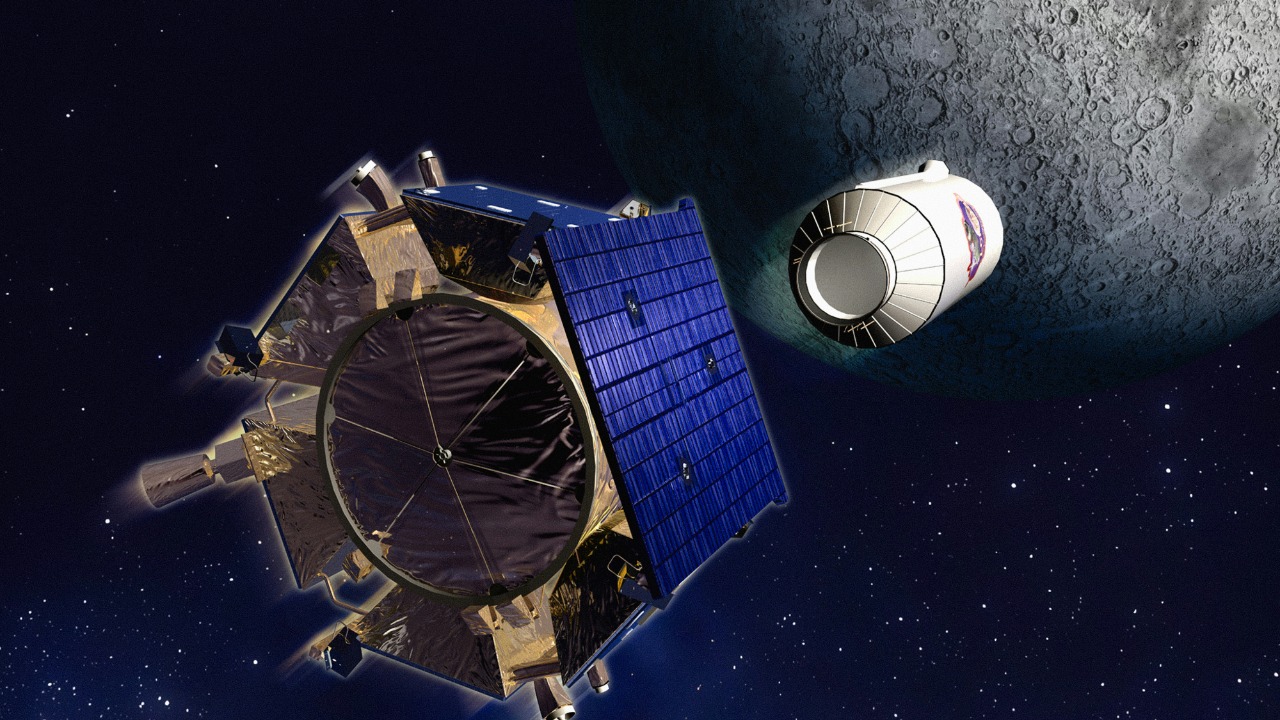

The proposed rescue hinges on a dedicated spacecraft that would rendezvous with Swift, attach or otherwise couple to the observatory, and then fire its own propulsion system to lift the combined stack into a higher, more stable orbit. Mission planners have targeted 2026 for this operation, positioning it as the inaugural example of a private vehicle physically reboosting a NASA astrophysics satellite rather than simply providing data relay or launch services. That timing is not arbitrary, because the longer Swift remains in its current orbit, the more fuel and precision will be required to counteract drag and regain a safe altitude.

Coverage of the plan describes the servicing craft as a commercial vehicle designed specifically to provide an “orbital boost” to Swift, with the 2026 flight characterized as a first of its kind mission that could open the door to similar contracts for other satellites if it succeeds. Detailed mission previews explain that the spacecraft will approach Swift in low Earth orbit, execute a series of proximity operations, and then raise the telescope’s altitude enough to buy several additional years of science, a sequence laid out in reporting on the orbital boost in 2026.

Inside the private mission’s business model

What makes this rescue especially notable is not only the technical choreography but the financial structure behind it, which leans on private capital and a service based model rather than a traditional NASA owned spacecraft. The company leading the effort is positioning itself as an in orbit logistics provider, effectively selling orbital boosts and life extension as a product that agencies and satellite operators can buy when their hardware starts to age. In that sense, Swift is both a customer and a high profile demonstration of a business that could eventually target commercial Earth observation fleets and communications constellations.

Descriptions of the mission emphasize that the telescope’s reboost is being organized as a commercial service, with the private team taking on development risk in exchange for the chance to prove its technology on a marquee NASA asset. Early write ups of the plan highlight how the company is marketing the Swift operation as a template for future contracts, presenting the telescope’s looming reentry as an opportunity to show that a relatively small spacecraft can deliver a significant extension of mission life, a framing that appears in coverage of the private mission to save NASA’s space telescope.

Launch logistics and community scrutiny

Even before the spacecraft leaves the ground, the mission has become a fixture on launch tracking calendars and in online spaceflight communities that follow every new rocket manifest. Enthusiasts have flagged the Swift reboost as a standout entry among the usual communications satellites and cargo runs, in part because it blends commercial hardware with a high value science payload that many astronomers rely on. That attention has turned the mission into a kind of public test, with every schedule update and hardware milestone dissected in real time.

Launch schedule aggregators already list the Swift servicing flight among upcoming missions, noting its target year and the fact that it will carry a spacecraft dedicated to rendezvousing with the telescope, a level of detail that has filtered into posts on community maintained calendars such as Space Launch Schedule. On discussion forums, users have debated the risks of docking with or grappling an aging observatory, trading links and technical speculation about how the private vehicle will manage attitude control and structural loads during the boost, conversations that have unfolded in threads like the private mission to save NASA space telescope discussion.

Why NASA is testing private rescue on Swift instead of Hubble

One of the most pointed questions I hear is why NASA is willing to let a commercial spacecraft physically interact with Swift while the agency has been far more cautious about similar offers for the Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble is larger, more complex, and historically serviced by astronauts, which raises the stakes for any new approach that might alter its orbit or structural loads. By contrast, Swift is smaller and was never designed for crewed servicing, which makes it a more natural candidate for a robotic demonstration that can tolerate a bit more risk.

Earlier this year, NASA publicly acknowledged that it had studied a proposal from a private company to send a commercial spacecraft to Hubble, potentially to reboost or even upgrade the observatory, but the agency ultimately decided not to move forward at that time. Officials cited the need to better understand the technical and safety implications of docking a new vehicle to such a critical asset, a caution that stands in contrast to the more experimental posture around Swift and is documented in reporting on NASA’s review of a private mission to save Hubble. In that light, Swift functions as a lower risk proving ground that could inform any future decisions about commercial servicing of Hubble or other flagship observatories.

A test case for the future of space science funding

Behind the technical drama sits a larger policy question about how the United States will pay for space science in an era of constrained budgets and rising launch costs. NASA’s astrophysics portfolio already includes major commitments like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which is being developed as a next generation observatory to study dark energy, exoplanets, and wide field cosmology. When agencies face pressure to fund ambitious new missions while also operating aging but still productive satellites, the temptation to offload some responsibilities to private partners grows stronger.

Advocates for robust public investment in space science argue that even as commercial services expand, core funding for research and flagship missions must remain stable to ensure long term discovery and the downstream benefits that flow into everyday technology. Analyses of NASA’s budget stress that protecting science accounts is essential for breakthroughs that eventually translate into advances in areas like communications, climate monitoring, and medical imaging, a case laid out in discussions of how protecting NASA funding supports both space exploration and daily life. At the same time, program overviews for missions such as the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope show how much capital is already committed to future observatories, which helps explain why relatively low cost life extension services for existing satellites are attracting attention inside and outside the agency.

Industry momentum and what success would signal

For the commercial space sector, the Swift mission is more than a one off contract, it is a chance to prove that in orbit servicing can be a repeatable business rather than a bespoke engineering stunt. Executives and engineers involved in the project have been promoting the planned reboost as a milestone for their companies and for the broader idea of satellite life extension, highlighting how a successful rendezvous and boost could unlock new markets. That narrative has spread through professional networks where space industry veterans trade notes on which firms are actually flying hardware versus pitching slide decks.

Posts from industry leaders describe the Swift rescue as a pivotal demonstration for private servicing, framing it as a moment when commercial players step directly into roles once reserved for government owned spacecraft, a sentiment captured in commentary on the private mission to save NASA space telescope. Public facing coverage has echoed that framing, with social media updates flagging the mission as a first of its kind attempt to give a NASA telescope an orbital boost using a commercial vehicle, as seen in posts that spotlight the Swift reboost mission. If the 2026 flight delivers the promised extra years of science, it will not only keep one observatory alive, it will send a clear signal that the line between public and private roles in space science is shifting in ways that will shape every telescope that follows.

More from MorningOverview