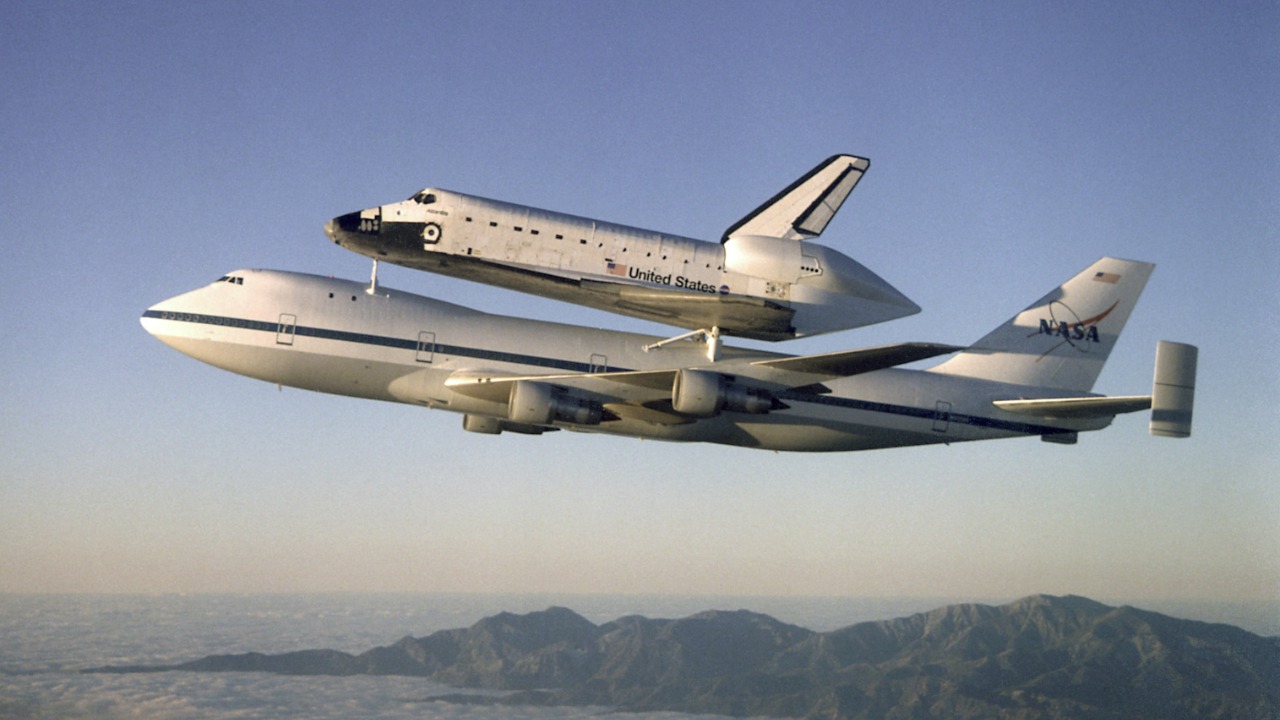

The choice of the Boeing 747 as the primary aircraft to ferry the Space Shuttle orbiter was a decision rooted in the jumbo jet’s size, strength, and availability during the 1970s. This unique piggyback method enabled safe overland and overseas movement of the shuttle, a feat of engineering that supported the program through its final missions.

Historical Need for a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft

With the advent of NASA’s Space Shuttle program, there arose a need for a reliable method to transport the orbiters between facilities like Kennedy Space Center and Edwards Air Force Base. The shuttles were too large for standard transport, necessitating a solution that could handle their size and weight. In the early 1970s, NASA evaluated various options, including modified military transports. However, the agency leaned towards a civilian airliner for reasons of cost and scalability. The Boeing 747, with its existing production line and impressive payload capacity, emerged as a frontrunner, leading to NASA’s acquisition of two surplus models.

The Selection Process Behind Choosing the 747

In 1974, NASA issued a request for proposals, prioritizing aircraft with a wide fuselage and high structural integrity to support the shuttle’s 150,000-pound weight. The Boeing 747 was selected over competitors like the Lockheed L-1011 due to its availability from scrapped airline orders and proven performance in heavy-lift scenarios. A 1976 contract awarded Boeing the modification task, establishing the SCA (Shuttle Carrier Aircraft) designation for the two 747-100 models.

Engineering Modifications to the Boeing 747

The 747 underwent significant modifications to fulfill its new role. The upper fuselage was reinforced with external struts and a custom cradle to secure the orbiter, including pylon attachments tested for aerodynamic stability. The engines were upgraded to four Pratt & Whitney JT9D turbofans to handle the added 230,000-pound gross weight during ferry flights, enabling the aircraft to reach speeds up to 250 knots. Avionics enhancements included new flight controls and displays to manage the shuttle’s drag, with initial tests conducted at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center.

Operational Flights and Key Missions

The first mated flight of a 747 with an orbiter occurred in 1977 using the Enterprise test shuttle. This flight validated the piggyback system’s safety over routes like California to Florida. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, SCAs ferried orbiters for 25 missions, including post-landing transports from Edwards to Kennedy. A notable 2012 flight saw Space Shuttle Endeavour piggybacked to Houston’s Johnson Space Center for retirement display, covering 1,200 miles from California.

Challenges and Innovations During Piggyback Operations

Despite the success of the piggyback method, it was not without challenges. Aerodynamic issues arose from the shuttle’s tile surface and shape, necessitating flight path restrictions over populated areas and special clearances for international legs. Crew training emphasized low-altitude handling, with pilots noting the 747’s stability even in turbulence while carrying Discovery or Atlantis. Maintenance demands increased due to the structural stresses, but the setup proved durable, logging over 1,000 hours of mated flight time.

Legacy of the 747-Shuttle Partnership

After the shuttle program’s 2011 retirement, the modified 747s found new life. One joined exhibits like the 2016 California Science Center display alongside Endeavour in vertical launch pose. The piggyback method influenced future space transport designs, such as SpaceX’s Falcon 9 recoveries, underscoring the 747’s role in NASA’s engineering history. Ongoing analyses, including 2021 retrospectives on the carrier’s mechanics, affirm the choice’s efficiency in enabling global shuttle logistics.