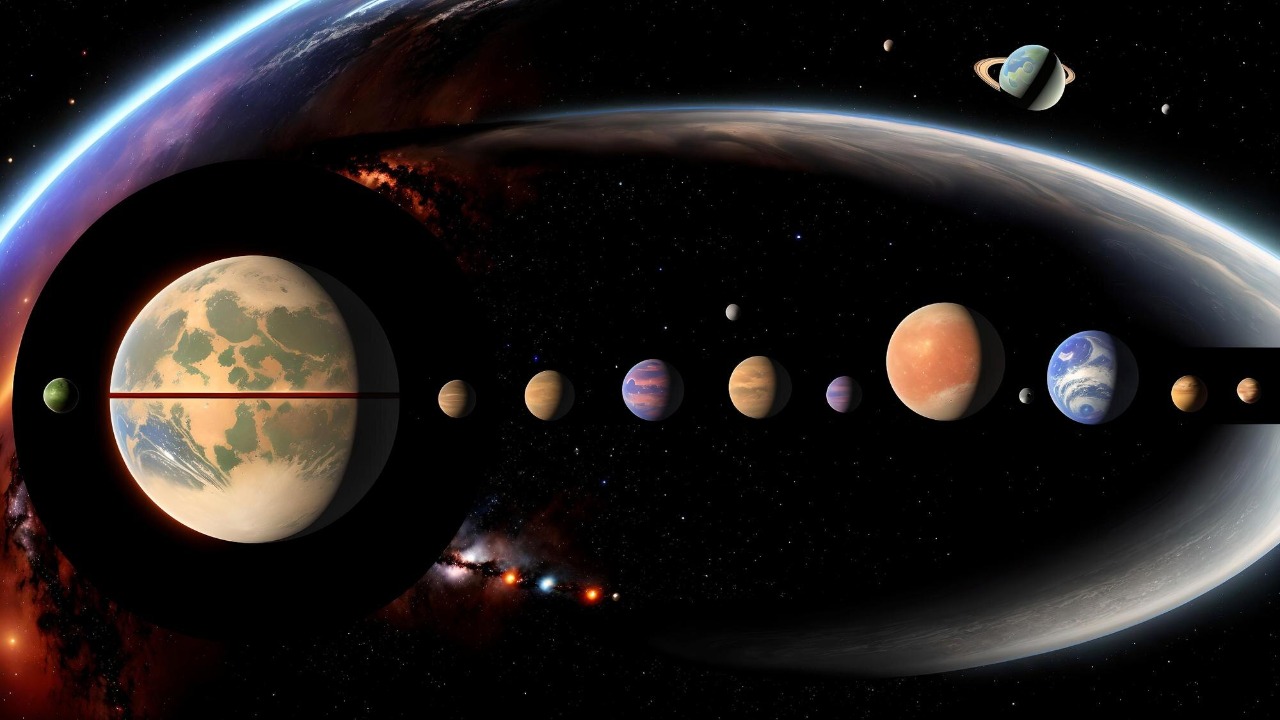

Across the Milky Way and beyond, planetary systems appear to fall into a few recurring blueprints, and recent exoplanet surveys suggest that just four layouts may dominate the universe. Drawing on Kepler and TESS statistics, along with targeted simulations and direct imaging, I can sketch how pebble-built rocky swarms, super-Earth chains, hot Jupiter dominos, and cold giant outskirts together account for nearly every known configuration.

Pebble Planet Swarms

Pebble planet swarms describe systems where numerous small, rocky worlds crowd the inner regions, and a 2023 study in The Astronomical Journal argues that this is the single most common layout. By analyzing Kepler and TESS data, the University of Chicago team concluded that “pebble planets,” roughly comparable to Earth or Mars in size, dominate about 50 percent of planetary systems when no gas giant forms early enough to disrupt the inner disk. In these architectures, the habitable zone is filled with compact rocky bodies that grow from streams of millimeter to meter scale solids, rather than from a few large planetary embryos. Numerical work backs this picture: in a detailed simulation, planetary scientist Hal Levison and colleagues showed that Earth, Venus, and a smaller Mars can arise naturally when pebbles drift inward and are trapped by growing protoplanets, reproducing the basic structure of the inner Solar System. That result strengthens the idea that pebble accretion is not a niche process but a universal engine for building rocky worlds.

Observations of compact rocky systems around low mass stars reinforce how common these swarms may be. One nearby red dwarf, for example, hosts a set of surprising rocky worlds that include a volcanic planet, a sub-Earth, and a likely water world, with a fifth planet in the habitable zone, all packed close to their small star; the discovery of these Surprising, Volcanic, Earth type planets shows how efficiently small stars can assemble multiple inner rockies. In the pebble swarm scenario, such systems are not exotic, they are the default outcome when no Jupiter sized body clears out the disk. For astrobiology, the stakes are obvious: if roughly half of all systems look like this, then the universe may be filled with chains of modest, potentially temperate planets where surface conditions range from lava oceans to deep global seas. For mission planners and telescope designers, that prevalence justifies focusing future instruments on detecting and characterizing small rocky planets in tight orbits, since they likely represent the most statistically common real estate for life.

Super-Earth Chains

Super-Earth chains form the second major planetary layout, consisting of two to four planets between about 1.5 and 2 times Earth’s radius locked into close, often resonant orbits. The same 2023 Astronomical Journal study that highlighted pebble planets found that these chains account for roughly 30 percent of observed systems, especially where there are no massive outer giants to destabilize the inner configuration. In these architectures, the planets are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, with densities that can range from rocky to water rich, and their orbital periods often fall into simple ratios such as 2:1 or 3:2. That resonant structure hints at a history of gentle migration through the protoplanetary disk, where planets formed farther out and then drifted inward together, locking into stable patterns instead of scattering. Because the planets are relatively large and close to their stars, they dominate current exoplanet catalogs, which helps explain why super-Earth chains appear so prominently in the statistics.

Evidence for these chains comes not only from transit surveys but also from detailed follow up of individual systems that show multiple super-Earths packed inside the orbit of Mercury. Some of these systems include planets with densities suggesting deep oceans, others look more like scaled up versions of Earth and Venus, and a few may even host atmospheres that telescopes can probe for molecules such as water vapor and carbon dioxide. The discovery of a temperate super Jupiter only about 12 light years from Earth, directly imaged by The JWST, underscores how improved instruments are beginning to reveal both inner chains and outer companions in the same systems, giving a fuller view of their architecture. For researchers, super-Earth chains are crucial testbeds for planet formation theories, because their masses and spacings encode how disks evolve and how migration proceeds. For the search for life, they offer a mixed picture: their large sizes and tight orbits make them easy to find and characterize, but their surface conditions may be more extreme than Earth’s, with stronger gravity and potentially thick atmospheres that challenge habitability.

Hot Jupiter Dominos

Hot Jupiter dominos describe systems where a single massive gas giant orbits extremely close to its star, within about 0.1 astronomical units, and its migration history has the potential to topple or eject inner rocky planets like a line of falling tiles. The University of Chicago analysis of Kepler and TESS data identified these hot Jupiter dominated systems as a distinct minority architecture, and while that study associated them with roughly 15 percent of the systems in its modeled sample, broader radial velocity and transit surveys indicate that such close in giants are intrinsically rare, with occurrence rates closer to 1 percent around Sun like stars. That tension highlights an important nuance: hot Jupiters are not common overall, but when they do form and migrate inward, they tend to reshape their entire planetary system, which is why they deserve a place among the dominant structural archetypes. Observations of WASP type planets, such as the extreme hot Jupiter WASP-12b, show how a gas giant like Jupiter can end up in a scorching orbit, and work on WASP systems suggests that there may be a billion or more hot Jupiter analogs across the galaxy despite their low frequency per star.

Follow up studies of hot Jupiter systems reveal that their dynamical impact can be complex. Some planetary systems with hot Jupiters appear to be stripped down, with the giant planet orbiting alone and little evidence for surviving inner rockies, consistent with the idea that migration scattered or engulfed smaller bodies. Other systems, however, show that not all hot Jupiters are solitary, and discoveries of multi planet configurations with a close in giant and additional outer planets demonstrate that the domino effect is not always complete. Theoretical work summarized in discussions of Planetary migration indicates that hot Jupiters can form through disk driven drift or through high eccentricity pathways that involve gravitational kicks from other Jupiters or stellar companions, with each route leaving different signatures in orbital tilts and eccentricities. For habitability, the stakes are stark: a hot Jupiter that sweeps through the inner system can strip away material that might otherwise build Earth like planets, so stars hosting these giants are less likely to harbor temperate rocky worlds in stable orbits.

Cold Giant Outskirts

Cold giant outskirts complete the quartet of dominant layouts, pairing distant Jupiter like planets beyond about 1 astronomical unit with compact inner rocky or super-Earth systems. The 2023 architecture study assigned only about 5 percent of known systems to this category, but that fraction is almost certainly an underestimate, because current transit surveys are biased against long period giants. Radial velocity work has already hinted that the Solar System may be unusual, with one Radial velocity survey concluding that Jupiter like planets have a frequency below 20 percent around solar type stars, which still implies hundreds of millions of such giants in the Milky Way. Direct imaging and high contrast techniques are beginning to fill in the picture: observations with large telescopes, including the ESO Very Large Telescope, have resolved cold giants at wide separations, and these detections show that massive planets can coexist with inner compact systems rather than always disrupting them. In some cases, the outer giant may even help stabilize the inner region by shepherding comets and planetesimals, much as Jupiter is thought to have influenced the early Solar System.

New facilities are also revealing how cold giant outskirts connect to more exotic populations. The James Webb Space Telescope has identified hundreds of rogue planets in the Milky Way and beyond, including waltzing pairs of Jupiter mass objects that drift without a star, and simulations suggest that some of these free floaters were once part of systems with cold giant outskirts before being ejected. At the same time, models of the outer Solar System hint that as many as five Earth like worlds may lurk in distant orbits, showing how difficult it is to fully census planets at large separations. For observers, cold giant outskirts are challenging targets, requiring long baselines and high sensitivity, but they are crucial for understanding how often Solar System like architectures emerge. If outer giants are indeed common at the 10 to 20 percent level, then a significant share of planetary systems may combine inner rocky planets with distant Jupiters, offering both potential abodes for life and natural laboratories for studying how giant planets sculpt debris belts, comet reservoirs, and long term climate stability.

More from MorningOverview