The interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS has swung back into view after passing behind the Sun, and its return is proving even stranger than its arrival. Instead of fading quietly into the dark, the Manhattan sized visitor has brightened, shifted color and revealed a wildly unstable spin, forcing astronomers to rethink what they thought they knew about icy bodies from other stars.

As I follow the new data and early analyses, what stands out is how quickly 3I/ATLAS has gone from a curiosity to a stress test for comet science and planetary defense. Its behavior is challenging basic assumptions about how comets form, fracture and interact with sunlight, and it is doing so in real time while telescopes and tracking networks scramble to keep up.

From anonymous speck to third confirmed interstellar visitor

When 3I/ATLAS was first flagged, it looked like just another faint, fast moving point of light until its trajectory gave it away. The object was clearly not bound to the Sun, cutting through the solar system on a hyperbolic path that marked it as a true interstellar interloper, only the third such body known to have arrived from around another star after 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov. That status as the third confirmed visitor from outside our solar system is what turned a routine detection into a global observing campaign focused on an object that would never return.

Early estimates suggested a nucleus roughly comparable in scale to a Manhattan sized block of ice and rock, large enough that even modest changes in its brightness or motion could reveal a lot about its internal structure. As it headed inward, scientists watched it fly straight toward our Sun on a steeply inclined path, tracking the way its coma and tail responded to increasing solar radiation in order to pin down whether it was a comet or an asteroid. Those observations, combined with its activity level, ultimately confirmed that 3I/ATLAS is a true comet and not an asteroid, with an icy nucleus and a surrounding coma that responded vigorously to sunlight.

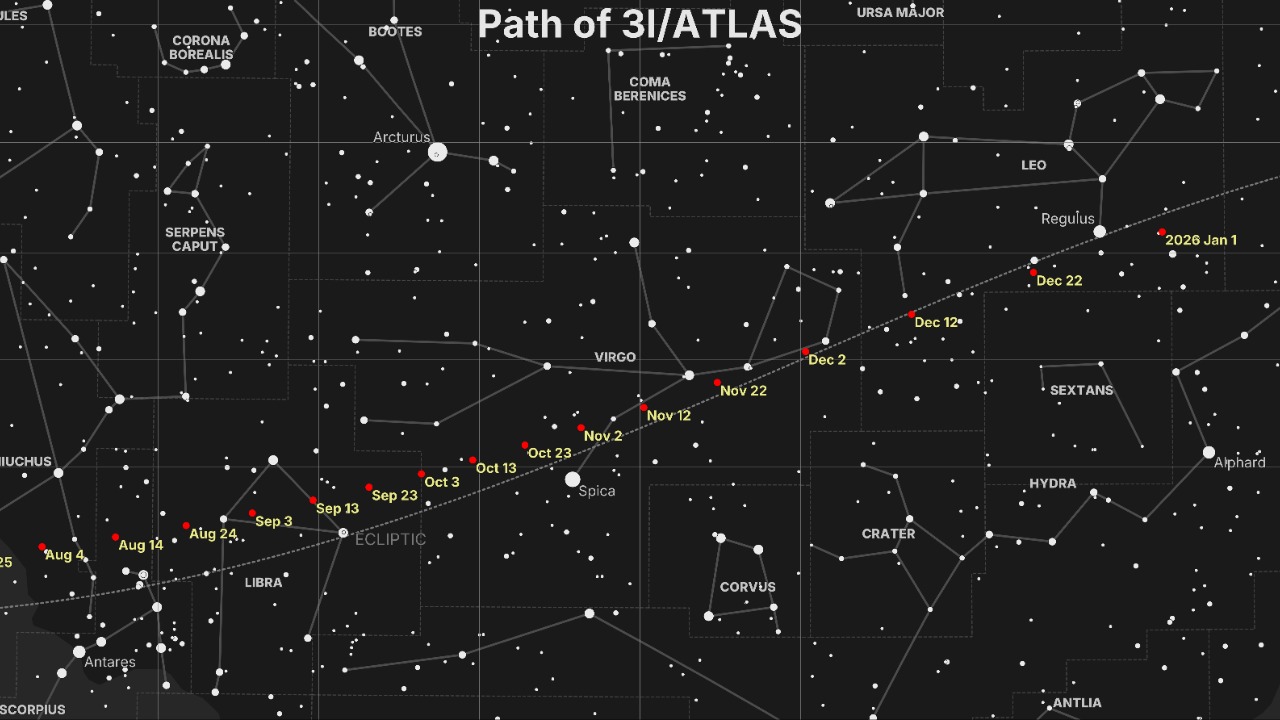

Disappearing behind the Sun, then a baffling blue comeback

For a stretch of its journey, 3I/ATLAS slipped behind the Sun from Earth’s perspective, effectively vanishing from most ground based telescopes. Astronomers expected that once it reemerged, it would follow a fairly predictable fading curve as it moved away from the intense heat and light near perihelion. Instead, when it came back into view, its light curve showed an unexpected surge in brightness and a strikingly blue hue that did not match standard models of dusty comet comae. That combination of a reappearance and a color shift is what has left many observers describing the comet’s behavior as baffling.

The renewed visibility of 3I/ATLAS after it cleared the Sun gave researchers a fresh look at its evolving coma and tail, and the data immediately suggested that something about its surface or internal structure had changed during its solar encounter. The object’s status as the third confirmed visitor from outside our solar system, combined with this unusual brightening pattern, has led some teams to argue that it may be exposing pristine material that formed around another star, material that reacts differently to solar heating than the ices seen in local comets. That argument is grounded in the way its post perihelion light curve deviates from expectations, as highlighted in analyses of its baffling blue light curve.

Why 3I/ATLAS is definitively a comet, not a rogue asteroid

One of the first classification questions for any new interstellar object is whether it is an inert rock or an active comet, and 3I/ATLAS has answered that decisively. From telescope observations, astronomers can tell that it is active, with an icy nucleus that is shedding gas and dust to form a coma and tail as it approaches the Sun. That level of activity, combined with the way its brightness responds to solar heating, is what allows researchers to state with confidence that 3I/ATLAS is a comet and not an asteroid, even though it originated around another star.

The distinction matters because active comets provide a direct probe of their birth environments, releasing volatile ices and complex molecules that can be analyzed spectroscopically. In the case of 3I/ATLAS, the outgassing pattern and the structure of its coma are already being used to infer the composition and layering of its nucleus, which appears to be more fragile and reactive than many long period comets that formed in our own outer solar system. That fragility is consistent with the way its activity has evolved, as documented in detailed reports of its unexpected brightening that emphasize how unusual its rapid changes are compared with comets at similar distances.

A weird wobble and sun facing tail that defy expectations

As more high resolution images have come in, one of the most striking features of 3I/ATLAS has been its unstable spin and the way its jets appear to wobble. Instead of a steady, simple rotation, the comet shows a complex tumble that causes its outgassing jets to sweep through space in a lurching pattern, producing a tail that at times points toward the Sun rather than away from it. That rare sun facing tail geometry is a direct consequence of how the jets are oriented relative to the comet’s spin axis and orbital motion, and it is not something typically seen in local comets.

The strange motion has been described as a weird wobble that is baffling astronomers all over again, because it suggests that the nucleus is either highly irregular in shape or has experienced recent fragmentation that altered its moment of inertia. Time lapse sequences of the comet’s rotation show the jets flickering and shifting in a way that is hard to reconcile with simple models of cometary spin, reinforcing the idea that 3I/ATLAS is dynamically unstable. Those visualizations of its weird wobble and the associated sun facing tail have become a focal point for teams trying to understand how internal stresses and outgassing torques can reshape an interstellar comet over a single passage through the inner solar system.

Interstellar chemistry and the puzzle of its rapid brightening

The unexpected brightening of 3I/ATLAS after it passed closest to the Sun has raised fundamental questions about its chemistry and structure. Typically, comets peak in brightness near perihelion and then fade as they move outward, but this object has shown a rapid increase in luminosity at distances where other comets of similar size and composition would be dimming. The reason for 3I’s rapid brightening at these distances remains unclear, and that uncertainty has become one of the central scientific puzzles surrounding the comet.

One possibility is that layers of volatile ices that were buried beneath a more refractory crust have been newly exposed by cracking or partial breakup, leading to a delayed surge in outgassing. Another is that the interstellar environment where 3I/ATLAS formed produced an unusual mix of ices that sublimate efficiently even at lower solar flux, creating a prolonged active phase. Whatever the explanation, the fact that an interstellar comet is still full of surprises at this stage of its outbound journey underscores how little is known about the diversity of small bodies that form around other stars.

Rare sun facing jets and what they reveal about the nucleus

The discovery of wobbling jets that at times drive a tail toward the Sun has given researchers a rare opportunity to map the active regions on 3I/ATLAS’s surface. In most comets, the dominant jets push material away from the Sun, creating a classic tail that streams outward along the solar wind. In this case, the geometry of the jets and the comet’s rotation combine to send material sunward, which then gets swept back by radiation pressure, producing a complex, folded tail structure that encodes information about the nucleus’s topography and spin state.

By modeling the changing orientation of these jets, scientists can infer where on the nucleus the most active vents are located and how they evolve as the comet rotates. The fact that 3I/ATLAS may have moved away from the Sun while still showing such a pronounced sun facing tail suggests that its activity is both intense and uneven, with certain regions continuing to erupt vigorously even as the overall solar heating declines. Detailed analyses of these weird wobbling jets are helping refine models of how outgassing torques can alter the spin of small bodies, which in turn affects their long term stability and fragmentation behavior.

Only the third of its kind, and a bridge to ʻOumuamua and Borisov

Context is crucial when assessing how strange 3I/ATLAS really is, and that context comes from the two earlier interstellar visitors, 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov. 3I/ATLAS is only the third object known to have entered our solar system from around another star, which means every detail of its behavior carries outsized weight in efforts to understand the broader population of interstellar small bodies. Where 1I/ʻOumuamua was an apparently inactive, elongated object and 2I/Borisov behaved more like a conventional comet, 3I/ATLAS seems to occupy a middle ground, with cometary activity but highly unusual dynamics and light curve evolution.

By comparing its composition, activity level and spin state with those of its predecessors, astronomers hope to build a statistical picture of how common different types of interstellar debris might be. The fact that the first three known objects span such a wide range of properties suggests that the population is highly diverse, which has implications for how planetary systems form and eject material into interstellar space. The recognition that 3I/ATLAS is only the third object known of this kind underscores why observatories are devoting so much time to tracking it even as it recedes into the outer solar system.

Planetary defense, black swan worries and talk of alien tech

Beyond pure curiosity, 3I/ATLAS has also become a test case for how planetary defense systems respond to rare, poorly understood threats. Its size, trajectory and interstellar origin have prompted some researchers and commentators to describe it as a potential black swan event, a low probability but high impact scenario that could stress existing monitoring and response frameworks. Astronomers and planetary defense teams are tracking the object closely, not because it is on a collision course with Earth, but because its behavior could reveal blind spots in how we detect and characterize fast moving interstellar bodies that might pose a future risk.

The same combination of strangeness and scarcity has also fueled speculation that such objects could harbor alien technology, an idea that sits at the fringes of mainstream science but continues to capture public imagination. While there is no verified evidence that 3I/ATLAS is anything other than a natural comet, the fact that a rare interstellar object can exhibit such unexpected behavior has encouraged some to argue that we should treat each new arrival as an opportunity to test even unlikely hypotheses. That perspective is reflected in discussions of 3I/ATLAS as a threat to humanity and a possible carrier of alien technology, even as most observational work remains focused on conventional cometary physics.

What the Manhattan sized visitor is teaching us about our own system

As 3I/ATLAS continues its outbound journey, the data it leaves behind are reshaping how I think about the solar system’s place in the galaxy. The Manhattan sized nucleus, with its unstable spin, wobbling jets and puzzling brightening, is effectively a sample of another planetary system delivered to our doorstep, and its behavior is forcing models of comet evolution to accommodate a wider range of initial conditions. By studying how its ices respond to the Sun, researchers are indirectly probing the temperature, radiation environment and chemical makeup of the region where it formed, which may differ significantly from the protoplanetary disk that produced our own comets.

At the same time, the intense scrutiny of 3I/ATLAS is driving improvements in survey strategies, data analysis pipelines and rapid response protocols that will benefit the study of future interstellar visitors and potential impactors. The experience of tracking an object that flew straight toward our Sun, vanished behind it and then reappeared with a baffling new set of behaviors has highlighted both the strengths and the gaps in current observing networks. Those lessons, first drawn when scientists began keeping a close eye on the massive object flying straight toward our sun, will shape how quickly and effectively we can respond the next time a strange interstellar body drops into the inner solar system.

More from MorningOverview