The race to reinvent the electric vehicle battery just crossed a line that had existed mostly in lab demos and investor decks. A small Finnish outfit, Donut Lab, says it has moved solid-state cells into real production vehicles, with packs that can go from empty to full in roughly five minutes and promise far higher energy density than today’s lithium-ion designs. If the claims hold up at scale, the shift from “fast charging” to “refueling speed” could arrive far sooner than most of the industry expected.

Instead of another incremental tweak to chemistry or cooling, Donut Lab is pitching a wholesale change in how batteries are built and integrated. Its solid-state architecture is already being shown on the road with partners, not just on a test bench, and the company is positioning its technology as ready for mass manufacturing rather than a distant research milestone. I see this as the first credible attempt to make five‑minute charging a commercial reality rather than a marketing slogan.

What Donut Lab is actually claiming

At the core of the announcement is a bold technical promise: an all solid-state cell that can be charged from zero to 100% in about five minutes while still fitting into production vehicles. Donut Lab describes its product as the world’s first all-solid-state battery in production vehicles, pairing that headline claim with specific performance figures rather than vague superlatives. The company is not talking about a one-off prototype, but about hardware it says is already integrated into road-going machines.

Those figures are unusually concrete for a battery launch. The cell is rated at 400 Wh/kg and Designed for 100 C charging, which is the kind of specification that, on paper, supports a full recharge in minutes rather than tens of minutes. Donut Lab also emphasizes that this is a Full production design, not a lab coupon, and that the architecture is meant to drop into existing vehicle platforms with minimal redesign. For an industry that has grown used to cautious roadmaps, the specificity of those numbers is part of what makes the claim so disruptive.

From CES stagecraft to real vehicles

The debut did not happen quietly in a white paper. Donut Lab chose CES as its coming-out party, using the Las Vegas tech show to frame its cells as a ready-made solution for automakers looking to leapfrog conventional lithium-ion. At CES, the company highlighted how its packs can be integrated into different platforms, positioning the technology as a modular building block rather than a bespoke science project. That choice of venue signals an intent to speak directly to both consumer electronics and mobility audiences. The most visible proof point came when Donut Lab and Verge Motorcycles rolled a bike onto the floor with the new pack inside. According to one detailed account, Donut Lab put five minute charging solid state batteries on the road with Verge’s TS lineup, using the motorcycle as a showcase for how quickly the cells can be charged and how compact the pack can be. Another description of the launch notes that Each partner showcases a different way solutions can be integrated, underscoring that this is meant as a platform play across multiple OEMs rather than a single halo product.

Why this counts as “first” in solid-state

Solid-state batteries have been promised for more than a decade, but until now they have largely lived in research labs or pilot lines. Donut Lab is staking a claim to be first by focusing on the phrase “mass-produced” and tying it to actual vehicles on sale. One report describes how Donut Lab presents the world’s first mass-produced solid-state battery capable of charging to 100% in 5 minutes, drawing a line between this product and earlier experimental cells that never left the lab.

Geography also matters here. A separate analysis points out that a small company in Finland, Donutlabs, has announced the world’s first production solid-state battery, emphasizing that this is not a giant incumbent but a relatively small player moving faster than better-funded rivals. By tying the “first” label to production status, integration with Verge Motorcycles, and the ability to charge to 100% in minutes, Donut Lab is trying to close off the usual wiggle room that surrounds breakthrough claims in battery tech.

The five-minute charge and what it really means

On its face, the idea of recharging an EV in roughly the time it takes to fill a gasoline tank is transformative. Donut Lab’s own technical page states that its pack can reach a Full charge in five minutes, and that it is Designed for 100 C operation, which is the kind of current load that would melt or destroy most conventional cells. The company frames this as a way to make charging stops feel like traditional refueling, eliminating one of the biggest psychological barriers to EV adoption.

Independent observers have seized on that figure as the headline takeaway. A widely shared discussion thread describes the World First Production Solid State Battery Charges in Just Minutes, highlighting the ability to recharge to full capacity in just five minutes and the claim that this can be done without the rapid degradation seen in current EVs. In a separate breakdown, a video analyst named Jan walks through what makes this battery so special, focusing on how the solid electrolyte and current handling differ from typical fast-charging packs. Taken together, these accounts suggest that the five-minute figure is not just a marketing flourish but a core design target.

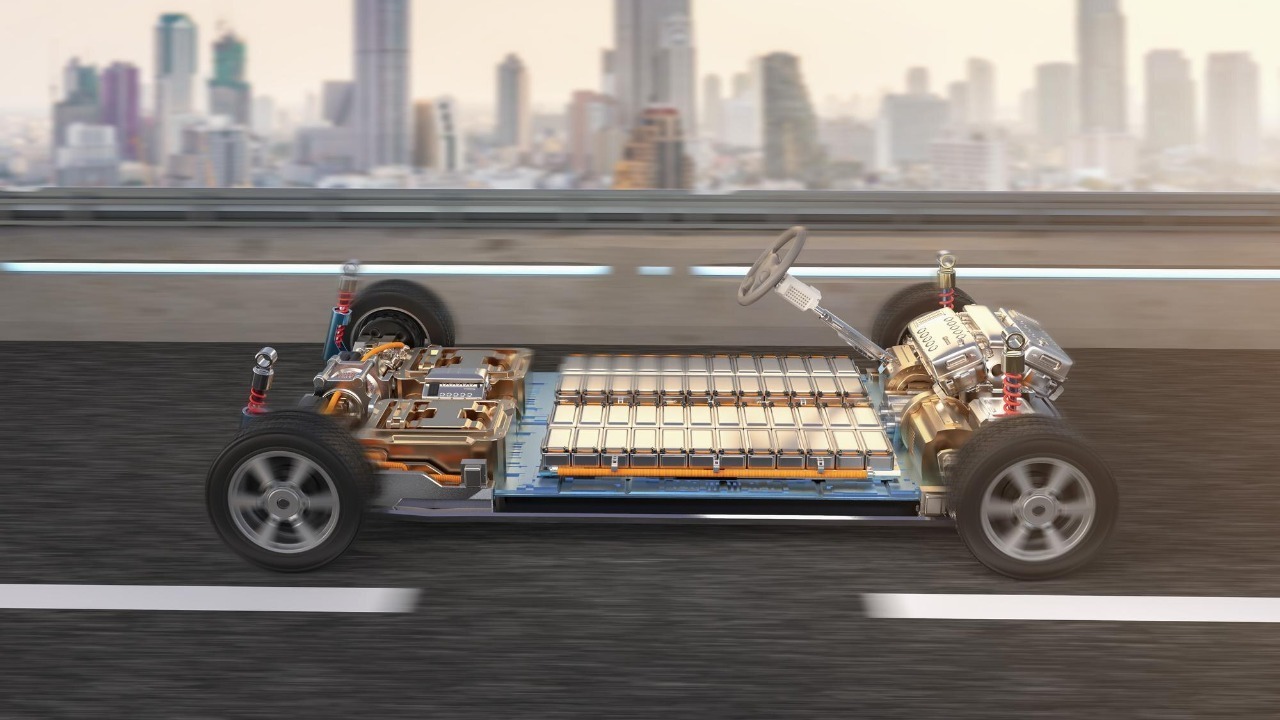

Inside the Donut Battery: chemistry and design

Donut Lab brands its product as The Donut Battery, and the company leans heavily on the phrase Solid State Power to signal that this is a full solid-state architecture rather than a hybrid. In practical terms, that means replacing the flammable liquid electrolyte used in most lithium-ion cells with a solid material that can tolerate higher temperatures and more aggressive charging profiles. The company’s own materials describe how this allows the pack to be heated above +100°C without the runaway risks that plague conventional chemistries, which is a key enabler for rapid charging.

At CES, one detailed account of the launch notes that The Donut Battery Solid State Power is Here At CES, Donut Lab and Verge Motorcycles made history by unveiling the pack in the Verge TS motorcycle lineup. That same account explains how replacing the traditional battery with this solid-state unit frees up packaging space and reduces weight, which is particularly valuable on a performance motorcycle where every kilogram matters. By anchoring the chemistry discussion in a real product, Donut Lab is trying to show that its design is not just theoretically superior but practically deployable.

Partnerships, platforms, and early adopters

For any new battery technology, the first commercial partners are as important as the chemistry itself. Donut Lab’s collaboration with Verge Motorcycles is the most visible, but the company is clearly signaling that it wants to be a supplier to multiple OEMs rather than a captive in-house solution. Its CES announcement stresses that Each partner showcases a different way solutions can be integrated, suggesting that the same core cell and pack design can be tuned for motorcycles, cars, and potentially even stationary storage.

Another detailed report on the launch explains that According to the company, its Solid State Donut Battery has been engineered for mass production and real-world operation, with testing in extreme conditions to validate those claims. That focus on manufacturability is crucial, because many promising solid-state designs have stumbled when moving from coin cells to large-format packs. By putting its first units into a premium motorcycle brand, Donut Lab is buying itself some room on cost while still proving that the technology can survive daily abuse.

How this shifts the EV charging conversation

If five-minute charging at 400 Wh/kg becomes widely available, the entire conversation around EV infrastructure changes. Instead of building huge numbers of moderate-power chargers where cars sit for half an hour, networks could focus on fewer, much higher power stations that turn vehicles around in the time it takes to grab a coffee. That would align EV refueling more closely with the way drivers already use gas stations, which could ease the transition for people who are skeptical of long charging stops.

From a consumer perspective, the psychological impact may be even bigger than the technical one. The idea that a battery can go from empty to 100% in minutes, as highlighted in the description that the battery is capable of charging to 100% in 5 minutes, attacks one of the most persistent myths about EVs, that they are inherently inconvenient on long trips. If early deployments with Verge Motorcycles and other partners show that this performance is repeatable without rapid degradation, it will be difficult for competitors to keep selling 30-minute fast charging as the state of the art.

Caveats, unanswered questions, and what comes next

For all the excitement, there are still major unknowns. Donut Lab has shared headline figures like 400 Wh/kg and five-minute charging, but has been more guarded about cycle life, cost per kilowatt-hour, and how performance changes in cold climates. The company’s own technical page on the battery emphasizes durability and safety, yet independent long-term data is not available, which is typical for a technology that is only just entering production.There is also the question of how quickly automakers beyond Verge will be willing to redesign their platforms around a new cell format. A video breakdown by Jan that examines the first production solid-state battery with 5-minute charging notes that integration is not trivial, even if the pack is designed as a drop-in replacement. Charging networks will need to adapt to much higher peak power draws, and regulators will want to see safety data from thousands of real-world charging sessions. In my view, the most realistic near-term path is that Donut Lab’s technology appears first in premium, low-volume vehicles where cost is less sensitive, then gradually filters down as manufacturing scales and competitors respond.

More from Morning Overview